When reports leaked about the contents of the Federal Communication Commission’s (FCC) plan to allow Internet service providers (ISPs) like Comcast to charge content distribution companies like Netflix or YouTube a premium for not slowing down their service, the outrage was palpable and immediate.

“Under this terribly misguided proposal, the Internet as we have come to know it would cease to exist and the average American would be the big loser,” charged Senator Bernie Sanders (D-Vt.) in a statement.

“If true, this proposal is a huge step backwards and must be stopped,” agreed former FCC commissioner Michael Copps. “If the Commission subverts the open Internet by creating a fast lane for the one percent and slow lanes for the 99 percent, it would be an insult to both citizens and to the promise of the Net.”

The fear among many is that the FCC’s abandonment of a principal called net neutrality, which holds that ISPs shouldn’t be able to discriminate in any way with regard to the content it pipes into the homes of millions of Americans, will lead to a situation where telecom companies will be able to gouge both consumers and Internet content providers, and effectively price innovative, new tech startups out of the market entirely.

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler has since back-peddled, insisting during a speech on Wednesday to the National Cable & Telecommunications Association that the ?fast lane” proposal was just a proposal, and net neutrality is still alive and kicking

Even so, many advocates of an open Internet remain skeptical. There are persuasive arguments to be made that ending net neutrality could ultimately be a net positive for the economy and, due to the revolving door between the the FCC and the telecom industry, it may be easier for proponents of those arguments to be heard than consumer-interest groups in favor of net neutrality.

Common carrier kerfuffle

In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the first major overhaul of the Telecommunications Act in six decades, which gave the FCC the authority to regulate ISPs as something called “common carriers.” Common carriers, a category that also consists of phone companies, are only allowed to make connections between parties without discriminating on content. If you try to reach Domino’s to order a pizza, a common carrier couldn’t direct you to Pizza Hut instead because the telecom company involved in making the connection had made a deal with Pizza Hut.

In 2002, FCC Chairman Michael Powell, who was appointed by President George W. Bush, reclassified ISPs from being common carriers, which are under Title II of the Telecommunications Act, to being regulated under Title I of the act—where they wouldn’t be stuck with such high levels of oversight, nor would they have to abide by the non-discrimination mandate applied to phone companies and other common carriers.

After Barack Obama—who campaign on a platform supporting net neutrality—succeeded Bush, he replaced Powell with Julius Genachowski. Genachowski put in net neutrality rules, but stopped short of reclassifying ISPs as Title II common carriers.

Last year, Genachowski was replaced by Wheeler, whose hand was forced on the net neutrality issue by a court decision that said that the FCC couldn’t impose net neutrality rules on ISPs as long they weren’t classified as common carriers.

FCC’s revolving door

The other side of this game of musical chairs is the upper echelons of the telecom industry. Prior to Wheeler’s selection to head the FCC, he ran both the National Cable Television Association and the Cellular Telecommunications & Internet Association, the most prominent lobbying groups for the cable and cell phone industries. After completing his own tenure at the FCC, Powell took Wheeler’s old job running the lobbying efforts of the nation’s biggest cable companies.

Powell and Wheeler are far from unique. Meredith Baker, who was appointed as an FCC Chair by Obama in 2009, took a job at NBC-Universal only a few months after approving the company’s controversial merger with Comcast. It was announced in April that Baker would take over Wheeler’s former role heading up the Cellular Telecommunications & Internet Association.

Writing in Vice, reporter Lee Fang outlines a few more examples.

There’s Daniel Alvarez, an attorney who had represented Comcast and wrote a letter to the FCC in 2010 arguing forcefully against net neutrality. He is now a legal advisor at the FCC working under Wheeler. Or Matthew DelNero, the agency’s deputy chief of wireline competition (which is central to the question of net neutrality), who previously worked as a lawyer at broadband provider TDS Telecom, a company that would likely receive a tangible material benefit from the end of net neutrality.

The problem is so widespread that, according to Timothy Karr, a senior director at the pro-net neutrality group Free Press, a full 80 percent of all FCC Commissioners have gone to work for the industries they were previously regulating after leaving public service.

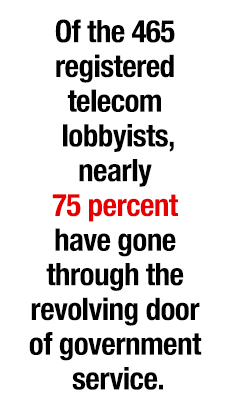

OpenSecrets.org reports that of the 465 registered telecom lobbyists, nearly 75 percent of them have gone through the revolving door of government service.

This number seems like a lot, which it is. But it still doesn’t count the army of unregistered lobbyists taking advantage of loopholes in election law to avoid reporting requirements—a sector that is rapidly consuming much of the traditional lobbying industry. It also misses the bureaucrats who go directly telecom executive roles rather than becoming lobbyists.

This doesn’t necessarily imply there’s a direct tit-for-tat going on. Both regulators and executives in industries that regularly deal with those regulators need people with lots of relevant experience.

“Whatever their motives, there’s an expertise there that’s appreciated on both sides,” Viveca Novak, editorial director of the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Responsive Politics, told the Daily Dot. ?It’s not necessarily a bad thing [to have people who are able to move back and forth]. You want regulators to be people with expertise on the subject. So it really is a balancing act.”

?When you have someone working for you that was close colleges with a current regulatory, it’s a real advantage. They can pick up the phone and schedule a meeting that someone without access might not be able to do,” Novak added. ?The revolving door certainly makes it incumbent on regulators to be aware of the interests of the people they’re taking to.”

When asked about his take about Wheeler’s tenure helming the FCC during a Reddit AMA on Thursday, Harvard Professor Lawrence Lessig, often considered the intellectual godfather of the entire open Internet movement and the author of recent book about all the ways corporate influence corrupts Washington, laid out the fundamental problem. ?People I like respect him,” Lessig noted. ?[They think he’s] the most decent lobbyist in the building. But he’s yet to demonstrate independence and progress.”

Conversely, there are people on the other side of the net neutrality debate who argue that corporate control over the FCC isn’t a given.

?As for a view that the FCC is too cozy with industry, it is easy to see it the other way, that the FCC is too cozy with the consumer lobby,” posited Roslyn Layton, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute’s Center for Internet, Communications, and Technology Policy. ?There were criticisms that the FCC was too close to Free Press during the Genachowski administration…I would say that these criticisms are made depending on whether you like the particular special interests that the FCC is catering to.”

A broken doorstop

There are, of course, some rules in place designed to ensure that, while the flow of personnel between business and the private sector remains unavoidable, a healthy separation is maintained.

One of the first things President Obama did upon entering office was sign an executive order meant to “shut” the revolving door—but it only slowed it down. The order prohibits administration officials from working on regulations or contracts substantially related to their prior employer for at least two years after leaving the private sector. It also bans former administration appointees from lobbying the executive branch during the remainder of President Obama’s term in office.

In practice, the rule hasn’t exactly been enforced as stringently as good government types might have hoped. Inside the order is a waiver clause, which allows for exceptions to be made if they are in the “public interest…[such as] exigent circumstances relating to national security or to the economy.”

It turns out that waivers aren’t even always necessary. Administration officials can skirt the rule by simply recusing themselves from discussions related to their former lobbying interests. And since the administration has been opaque on exactly how many recusals occur, PolitiFact has labeled the president’s campaign pledge to cut to enact strict rules on lobbyists working in his administration as a “broken promise.”

When it comes to the issue of net neutrality, there are some things that people in support of the concept can do to exert influence over regulators.

“[I]f the FCC was sufficiently motivated…[it could be] convinced that their proposed rule is a bad idea,” Michael Weinberg, vice president of the nonprofit group Public Knowledge told the Daily Dot. “In light of that, our job is going to be to convince the FCC that the proposed rule is a bad idea.”

However, that convincing may come in the form of companies that are just as politically influential as the ones supporting net neutrality.

Tech industry behemoths like Google and Yahoo have publicly mulled waging their own lobbying assault in favor of net neutrality. These Silicon Valley giants wouldn’t be doing this out of the goodness of their hearts—the end of net neutrality would undoubtedly result in their having to pay a toll to ISPs, something that would eat away at their profit margins.

At the end of the day, it may end up that the only thing capable of besting the efforts of one powerful corporate interest are the efforts of an even more powerful corporate interest.

Democracy in action, everybody, democracy in action.

Photo by Adrian Cable/Geograph