The FBI has been misrepresenting the number of times it was locked out of an encrypted phone connected to a criminal investigation.

A damning report from the Washington Post describes how the agency grossly exaggerated the number of devices it couldn’t access to make a stronger argument for addressing “Going Dark,” or spreading encrypted software that blocks investigators’ access to digital data.

The bureau claimed investigators were locked out of almost 7,800 devices linked to crimes last year when the actual number is somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000. FBI Director Christopher Wray referenced the inflated figure in January when he called encrypted electronics an “urgent public safety issue.” Attorney General Jeff Sessions similarly cited the figures earlier this month.

“Last year, the FBI was unable to access investigation-related content on more than 7,700 devices—even though they had the legal authority to do so. Each of those devices was tied to a threat to the American people,” he said.

The FBI became aware of the inaccurate statistics about a month ago and launched an audit to determine the actual number. Early figures suggest it’s closer to 1,200 phones, though that’s expected to change as more information becomes available. Its latest audit will likely take weeks to complete.

The FBI acknowledged the mistake in a statement to the Post but blamed “programming errors.”

READ MORE:

- How to encrypt an iPhone in seconds

- The best free VPN to maintain your privacy online

- Police are using the fingerprints of dead people to unlock iPhones

“The FBI’s initial assessment is that programming errors resulted in significant over-counting of mobile devices reported,’’ the FBI said in a statement. It went on to blame the use of three different datasets for causing phones to be counted more than once.

According to the report, only 880 encrypted phones couldn’t be unlocked in 2016. Many critics figured the jump in those numbers didn’t add up. It’s not clear if the figures from two years ago are still accurate.

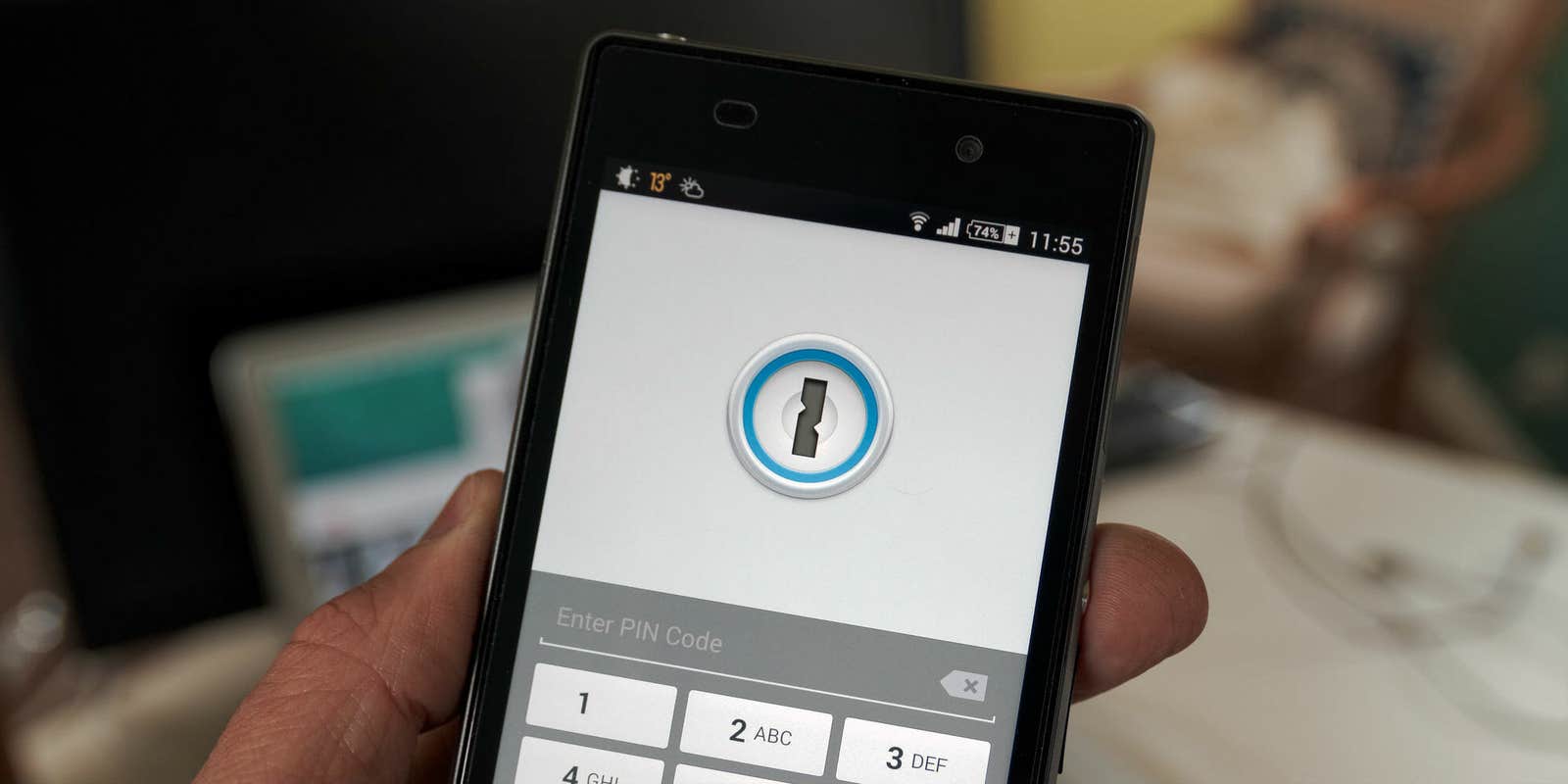

The heated debate over whether law enforcement should be given tools to access encrypted devices connected to crimes was ignited following the 2015 terror attack in San Bernardino, California. The shooter’s phone, an iPhone 5C, was locked with a passcode. FBI agents struggled to get in and eventually resorted to asking Apple for a backdoor. The company refused and was sued. The FBI eventually dropped the charges after it gained access with help from an unidentified third party, but that did little to resolve the dispute.

Similar cases have surfaced over the years. Most recently, the FBI served Apple a search warrant to access the iPhone of Devin Kelley, who killed 26 people in Sutherland Springs, Texas, in November. Again, Apple refused. The FBI and other law enforcement authorities have resorted to using less traditional methods to unlock devices. It was recently discovered that police are using the fingers of dead people to unlock Apple’s TouchID sensors. And the State Department spent $15,000 on Greyshift, a black box designed to break into iPhones.