The Facebook Oversight Board announced its much-anticipated decision regarding the social media giant’s ban of former President Donald Trump on Wednesday.

The Board found that Facebook was “justified” in banning the former president but kicked the decision back to the company, saying it disagreed with the indefinite nature of the ban.

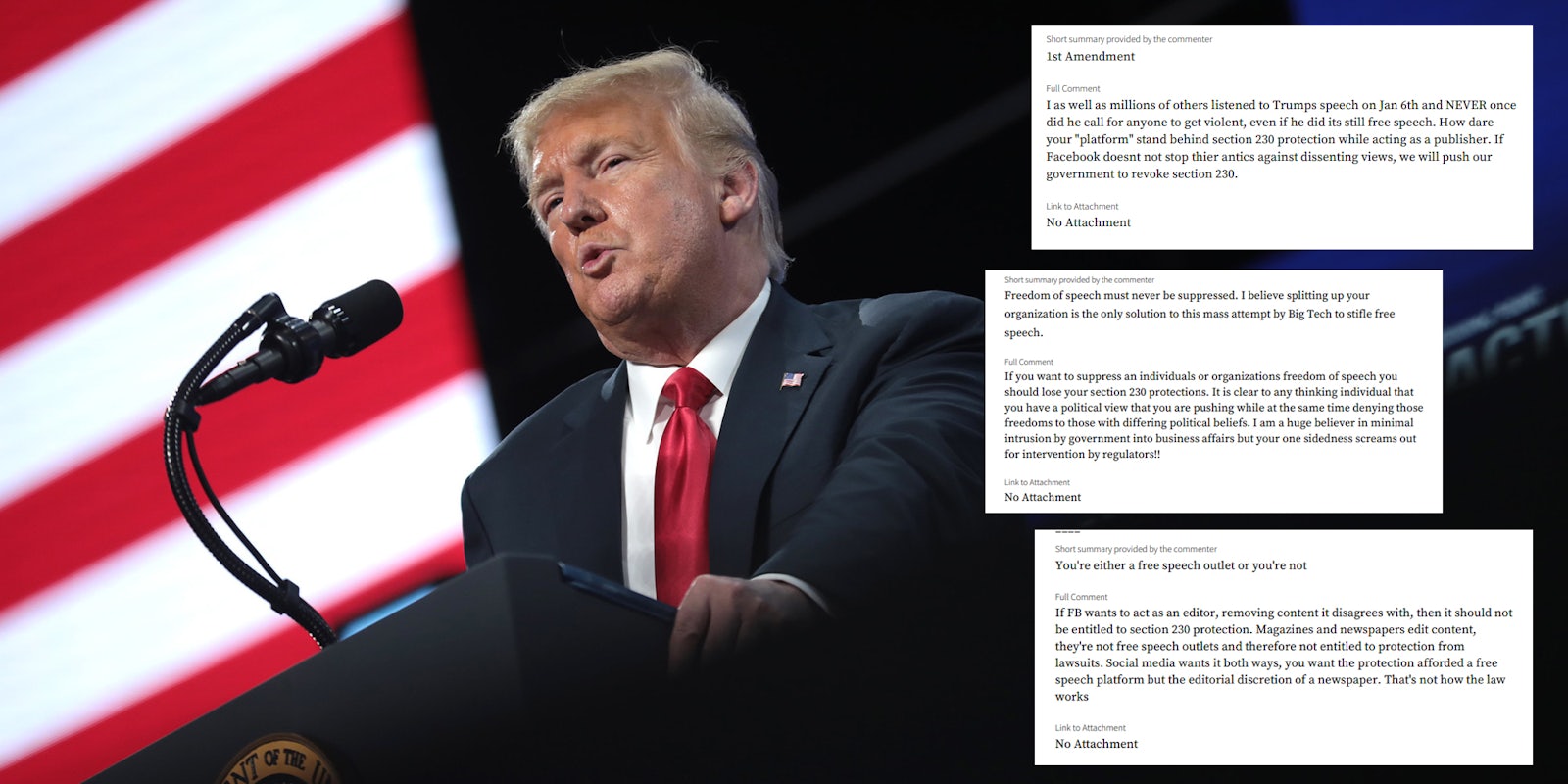

As part of the process, the Board collected comments from the public, and ultimately more than 9,000 people chimed in. Those public comments were also released on Wednesday, and perhaps unsurprisingly, they are filled with people griping about Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

Section 230 is an important internet law that shields all websites from being held liable over what users post on them. It’s been hailed as “one of the most valuable tools for protecting freedom of expression and innovation on the internet” and experts have warned that changing or repealing the law could have major ramifications online.

Despite this, Section 230 has become a target for lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. In fact, Trump spent much of his last few months in office ramping up pressure to repeal the law. Much of the criticisms about Section 230 come from grievances about big tech companies, but changes or a repeal to the law would effect any website where users generate content.

Give Trump’s fixation on Section 230, it’s not surprising that many of the people who wrote to Facebook’s Oversight Board about the former president’s ban were misinformed about the law.

The biggest misinterpretation in the public comments was the notion that to get Section 230 immunity, a website needs to distinguish itself as a “publisher” or “platform.”

This notion has been parroted by people like Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and as numerous experts have pointed out—like the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and TechDirt—it has no basis in reality.

EFF debunked the idea last December in a blog post:

Rather than enshrine some significance between online ‘platforms’ and ‘publishers,’ Section 230 intentionally nullifies any distinction that might have existed. Contrary to popular misconception, immunity is not a reward for intermediaries that choose the path of total neutrality (whatever that means); nor did Congress enact Section 230 with an expectation that Internet services were or would become completely neutral. Section 230 explicitly grants immunity to all intermediaries, both the ‘neutral’ and the proudly biased. It treats them exactly the same, and does so on purpose. That’s a feature of Section 230, not a bug. So online services did not self-identify as ‘platforms’ to mythically gain Section 230 protection—they had that already.

TechDirt goes on to note that the word “platform” isn’t even in Section 230, and elaborated on it in another blog post.

The law does distinguish between ‘interactive computer services’ and ‘information content providers,’ but that is not, as some imply, a fancy legalistic ways of saying ‘platform’ or ‘publisher.’ There is no ‘certification’ or ‘decision’ that a website needs to make to get 230 protections. It protects all websites and all users of websites when there is content posted on the sites by someone else. To be a bit more explicit: at no point in any court case regarding Section 230 is there a need to determine whether or not a particular website is a ‘platform’ or a ‘publisher.’ What matters is solely the content in question. If that content is created by someone else, the website hosting it cannot be sued over it.

Despite this, the misconception about the law has lived on, and it is riddled throughout the public comments about Trump’s ban.

Much of the approximately 147 comments mentioning Section 230 seem to think Facebook’s decision to ban Trump somehow nullifies the law’s protections. (It doesn’t).

“If FB wants to act as an editor, removing content it disagrees with, then it should not be entitled to section 230 protection,” one person wrote to the Oversight Board.

“Facebook and many other social media sites are protected by Section 230, a federal law preventing them from being held liable for the content on their platforms. Therefore, they should not in any way censor content,” another person wrote.

“If Facebook wishes to censor political speech vis-à-vis the president’s comments on January 6th, it should consider itself to be a publisher of speech and forswear any protections it might have under Section 230,” one pro-Trump person wrote.

“How dare your ‘platform’ stand behind section 230 protection while acting as a publisher,” another person wrote.

There are dozens of other Section 230 hot takes in the public comments.

While there is clear fervor among some people in the Facebook comments to change the law, that feeling is also reflected in Congress.

Numerous bills have been introduced that seek to change Section 230 from both Republicans and Democrats. None of them have gained much traction yet.

Even Facebook itself has said that it would be open to changes to Section 230, but as advocates have pointed out, changes to the law could actually strengthen big tech companies since they would have the financial ability to weather the sudden liability over what users post.