Silicon Valley companies are struggling to live up to promises of vastly improving diversity, as evidenced by Facebook’s most recent diversity report released on Thursday, which remains largely unchanged from one year ago.

Facebook excused its incremental diversity improvements in part by blaming the ethnic and gender imbalances within its ranks on the public education system and “the pipeline”—the idea that there are not enough people from underrepresented groups in the talent pool who can fill tech jobs.

The number of women in the workforce at Facebook increased one percent to 33 percent; meanwhile, the number of Hispanic and Black employees in the U.S. stayed at four percent and two percent, respectively.

In a statement that has the tech industry and diversity advocates reeling, Maxine Williams, Facebook’s Global Head of Diversity, said: “It has become clear that at the most fundamental level, appropriate representation in technology or any other industry will depend upon more people having the opportunity to gain necessary skills through the public education system.”

There are numerous efforts to improve computer science education at all levels of schooling (including Facebook’s $15 million donation to Code.org), and while there is a push to teach kids to code in classrooms and at home to fill future tech jobs, the idea that there just simply isn’t enough existing diverse talent for companies like Facebook to recruit has been debunked.

Black and Hispanic computer science and computer engineering students are graduating from top universities at twice the rate tech companies are hiring them, according to a 2014 report from USA Today.

Bethanye McKinney Blount, a founding member of diversity and inclusion organization Project Include and founder of Cathy Labs, said that a lot of the pipeline narrative centers around the technical side of companies, a flawed excuse that doesn’t account for a lack of diversity in other, non-technical aspects of the company.

“We have this artificial narrative that we’ve slapped onto these organizations suggesting that because the products we interact with are driven by engineers, and the cultures are founded by engineers, that the company is wholly populated by engineers,” McKinney Blount said in an interview. “And that’s false.”

The non-technical side of companies tend to have more gender parity, she said, but you don’t see the same consistency regarding employees of color. This rings true at Facebook.

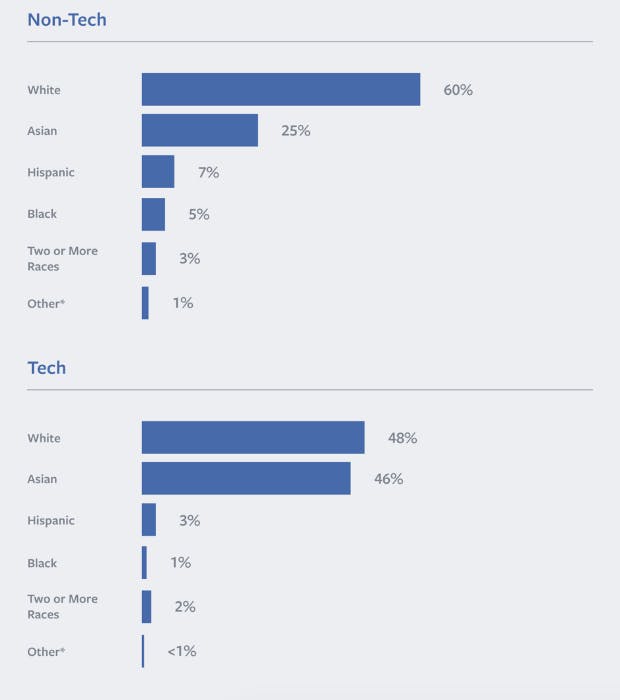

Facebook breaks down diversity by gender and ethnicity, and technical and non-technical teams. On the tech side, 83 percent of employees are men, while the non-tech teams are 53 percent women.

In the U.S., 48 percent of people on Facebook’s technical teams are white, 46 percent are Asian, and Hispanic and Black employees are just three and one percent, respectively. Non-technical Facebook workers in the U.S. are 60 percent white, 25 percent Asian, seven percent Hispanic, and five percent Black.

Further, the focus on the pipeline obfuscates other issues regarding diversity, namely retention and the idea that even when underrepresented minorities get hired at companies, they don’t stay, and fall out at a higher rate, she said.

Williams’s post touched on efforts Facebook is taking to improve hiring and retention of people from minority groups, including short, medium, and longterm efforts in HR, recruiting, and university training programs.

A spokesperson for Facebook told the Daily Dot one initiative called the “diverse slate approach” is modeled after the NFL’s Rooney Rule that requires teams to interview minority candidates for jobs. At Facebook, there is a guideline in place that the company will not make a call on hiring for a position until they see a candidate from an underrepresented group.

Other efforts to improve hiring include a video for candidates that prepares them for coding interviews ahead of time so they know what to expect, and managing bias classes. The classes aren’t mandatory (though nothing at Facebook is mandatory, the spokesperson said) and 75 percent of people have taken it, with nearly 100 percent of people at management levels and above completing the training. Additionally, the FBU training program for underrepresented students grew to 170 engineering students this summer, and a “handful” of former participants were hired full-time this year.

Improvements to hiring and retention and efforts to increase computer science education are helpful, but there is no quick fix for changing a company culture that’s largely white and male.

Kayla Smith, a former Facebook network engineer, left the company because of a culture she felt was not diverse or inclusive. She was the only woman on the multiple network engineering teams, and she said infrastructure teams at Facebook tend to have fewer women than other parts of the company.

“Diversity doesn’t mean anything without inclusion, because you hire a diverse candidate and they just wither when they get there. Then they leave,” Smith said in an interview. “I would go to team meetings and people would talk about new projects I’d never heard of, because they came up with idea while they were hanging out together. I was excluded from being a part of anything to the point where I became irrelevant. I wasn’t brought into the fold. I was sort of left behind.”

Smith said that the company offered voluntary unconscious bias training during her time there, and while she elected to go, she said the people who could most benefit from it didn’t sign up for the training. Because these large companies can be successful without diversity, it gives the impression that they’re doing everything right, she said.

Another former Facebook employee who asked only to be identified as a 30-something white male, said that some of Facebook’s culture may be unwelcoming to people from minority groups, including being very hard on people’s code during code reviews. He said people make fun of themselves through memes, but discussions can become pretty heated; for individuals who are already being held to a higher standard than others, which is true for many minority groups, this behavior can be discomforting.

However, he said, “Facebook had made a lot of progress on firing or reforming the most unprofessional people, regardless of talent, and I think that’s important for making people feel like they can ‘bring their whole selves to work.’”

Some of the recruiting strategies Facebook implemented included reaching out to historically Black colleges and universities, and changing parts of the interview process to make people feel more comfortable demonstrating skills. But although most of the company was aware of diversity efforts, people didn’t really understand why or how they could contribute, he said.

“There was a lot of concern about creating any perception of ‘lowering the bar,’ though there was at least some willingness to change the interview process to make sure we weren’t rejecting people for reasons that had nothing to do with the things we were trying to measure, such as nervousness coding on a whiteboard,” he said. “Facebook created some interview prep materials and started letting people code on laptops in their onsite interviews if they didn’t want to code on a whiteboard.”

On Twitter, a former Facebook engineering manager mentioned a similar sentiment.

but as a former hiring manager there, i can 100% attest that “lowering the bar” was mentioned basically every week w much handwringing/agony

— Charity Majors (@mipsytipsy) July 14, 2016

The stereotype of lowering the bar—that somehow companies will have to hire less talented folks in order to meet a diversity standard—is pervasive in tech company culture. As Slack engineer Leslie Miley explained when he left Twitter last year, saying that you’re committed to diversity, but don’t want to “lower the bar” puts in everyone’s mind that minority employees have less experience or are not as good as their peers.

For Dartmouth computer science student Kaya Thomas, Facebook’s insinuation that a lack of diverse talent is the reason why the company barely managed to move the needle on its diversity efforts renders her, and her Black and Latinx colleagues, invisible to the tech industry.

In an essay published shortly after the Wall Street Journal’s report on Facebook’s diversity data, Thomas said that Black and Latinx talent exists, but the tech industry refuses to see it.

When I saw this article I had to fight back tears. I thought about all the work I’ve put into to get to where I am today and wondered will it even matter when I start my job search in a few months. According to most tech companies, if I can’t pass an algorithmic challenge or if I’m not a “culture fit” I don’t belong. I haven’t even started my first full-time job yet and I’m already so tired of feeling erased and mistreated by the tech industry. I’ve worked so hard to make myself visible over the last few years so it hurt me to see Facebook make such false statements. What more must students of color do to make it clear that we are qualified to be in this industry?

Another problem that stems from large companies putting the emphasis on a pipeline or education system, is that it shows everyone else that diversity and inclusion and retention are problems too big for others to tackle, too.

In an industry that values open-source solutions to problems in software and hardware, a similar mindset is applied to culture; adopting the excuses of their predecessors.

“When you do have a big tech coming out and saying, ‘Well we’ve solved this problem, and we know this problem isn’t us,’ it sort of is giving permission to these smaller companies to say, ‘Wow, if that giant company can’t solve it, I’m not even going to try,’” McKinney Blount said.

Project Include provides resources focused on small and mid-size companies who want to improve diversity and inclusion, through research, recommendations, tools, and materials that can immediately affect change. From modifying interview language, to conflict resolution, to retention, Project Include can provide solutions that go beyond lip-service excusing companies from making any real dent in their numbers.

Tech companies began releasing annual diversity data in 2014 in an effort to be more transparent, after numerous calls for them to be more open about hiring and representation. Since then, data show minimal improvements. Some companies are taking a more radical approach, going beyond simply releasing data, and making initiatives and strategies public.

Last year, Pinterest released its data-driven approach to diversity, citing goals in line with the slow diversification across the industry, an honest proposal to improve in 2016. The company has not released information for this year, so it’s unclear if Pinterest achieved its goals.

Facebook is now facing significant criticism over what people consider diversity failings, especially for placing so much emphasis on the pipeline. For Smith, and many underrepresented workers in technology, an exclusionary culture can often be blamed when diverse candidates leave the company.

“When I think about Facebook abstractly, it’s like wow, they’re really trying for diversity. In actuality, there are different teams there who maybe aren’t as wonderful as the leader,” Smith said. “It was lonely. It’s one of those things where no individual person is mean. It’s the isolation of people not working with you.”

Facebook said it will continue to push its diversity efforts forward, and it is investing a lot in weeding out biases that contribute to challenges recruiting and retaining diverse talent. In its post, Facebook acknowledged it has “a lot of distance to cover.”