Facebook is to conspiracy theories what oxygen is to fire.

Ebola, autism, global warming—you’ve seen them all before, maybe from a weird uncle or a strange schoolmate.

By opening a direct path from producer to consumer of news and all manner of content, Facebook has changed the way its 1.4 billion users become informed, debate, and shape their opinions, according to new research from a group of Italian and British academics. On a wide range of topics, conspiracy theorists are loud and numerous on the social network, getting sucked deep into their conspiracy’s echo chamber and then spreading the ideas like so many flames.

“It recalls that the idea of the rational man is really far from reality.”

“Such a disintermediation weakened consensus on social relevant issues in favor of rumors, mistrust, and fomented conspiracy thinking,” the researchers explain.

“Disintermediation” means that users tend to cluster into likeminded and polarized groups, strengthening the echo chambers that build and reinforce conspiracy-minded narratives.

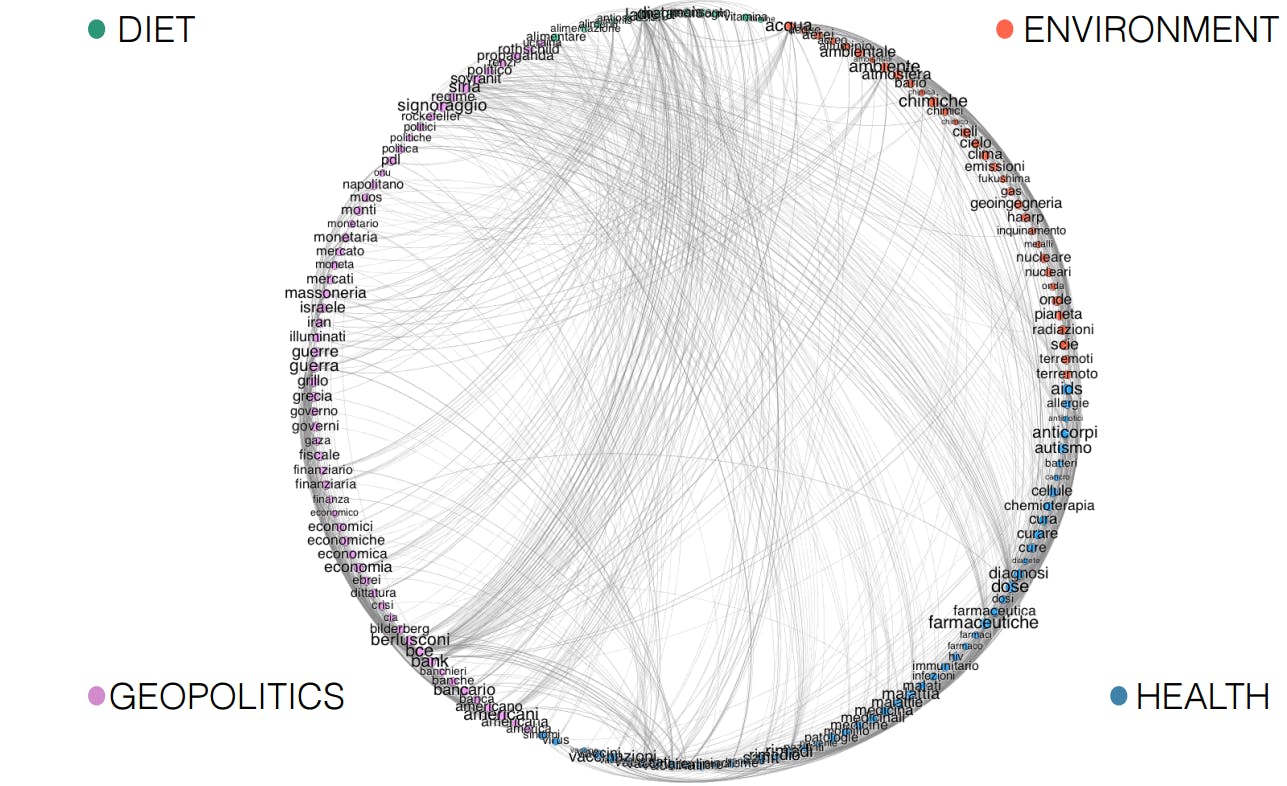

The scientists dove into Italian Facebook in particular by examining over 750,000 conspiracy theory enthusiasts to discover just how the theories are consumed on the world’s largest social network.

“You can find tons of weird way to explain phenomena or to convey general paranoia in something that recall the schema of a secret plot,” researcher Walter Quattrociocchi told the Daily Dot. “Chemtrails or the narrative about [genetically modified organisms]. More than shocking, [it’s] really sad. [In] some way it recalls that the idea of the rational man is really far from reality. In another study we showed that they can trust almost everything (e.g., Chemtrails to spray sildenafil citratum—the active ingredient of Viagra).”

The supposed link between autism and vaccines, deliberately induced global warming by chemtrails, and an overarching New World Order plot are among the conspiracy theories that burn brightest on Facebook today, the researchers found.

These theories have real world consequences, the researchers point out. During the 2014 Ebola epidemic, for instance, rumormongering built a deep distrust of healthcare workers operating in West African nations, making their job of caring of the region’s health much more difficult.

The “first major outbreak of the social media era,” as Ebola was called, quickly became infected by conspiracy theories.

Thanks in large part to social media, theories quickly crossed the Atlantic. President Obama invented Ebola, some said, or at least welcomed it here to punish white people, according to hugely influential talk radio host Rush Limbaugh. Theories like these inspired enough fear to have a large but non-rational influence on the national debate over how to deal with the disease.

“The [biggest] surprise was in the number of people (no matter about the level of education) join this universe,” Quattrociocchi wrote. “Another point is that, once started, misinformation is really hard (if not impossible) to stop.”

The most widely discussed theories fall into four categories: environment (e.g. global warming or nuclear energy); diet (e.g. vitamins or water supplies); health (e.g. pharmaceuticals or autism); and politics (e.g. American banks or Israeli-Iran relations), which attracts the most persistent conspiracy-subscribers of them all.

Political discussion—the end of the U.S.A. and establishment of a New World Order, for instance—attracts many times more readers and inspires significantly longer debates in the comment sections in a way that no other topic can rival.

“Because globalization introduced new phenomena and increased the effort to deal with reality (financial crisis, immigration, etc.), and there is the profound need to synthesize and reduce to something that reduce the cognitive pay-off,” Quattrociocchi wrote. “It’s easier to attribute the global warming or the financial crisis to a secret plot by powerful individuals.”

The diet theorists are generally less numerous and less persistent in commenting and spreading the ideas, though they’re still bullish on their ideas and are sharing posts on the topic at nearly a comparable rate to the other theorists.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the research asserts that conspiracy theorists regularly jump from one theory to another, with the more active users jumping more and more rapidly to new theories bent on explaining reality in a way that is, theorists often say, being ignored by the mainstream.

Online debunking campaigns have at times been worse than ineffective, the researchers assert. They can create “a reinforcement effect in usual consumers of conspiracy theories” leading to “disengagement from mainstream society and from officially recommended practices—e.g. vaccinations, diet, etc.”

Although this particular research paper is about Italian Facebook, the same scientists are currently studying American users. In the U.S., they found, “any attempt to debunk biased beliefs is not effective” because attempts reach very few people and end up once again reinforcing the conspiracy theories beliefs.

“Social media fostered the production of an impressive amount of rumors, mistrust, and conspiracy-like narratives aimed at explaining (and oversimplifying) reality and its phenomena,” the researchers wrote.

You can read the full paper below.

Photo via ** RCB **/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)