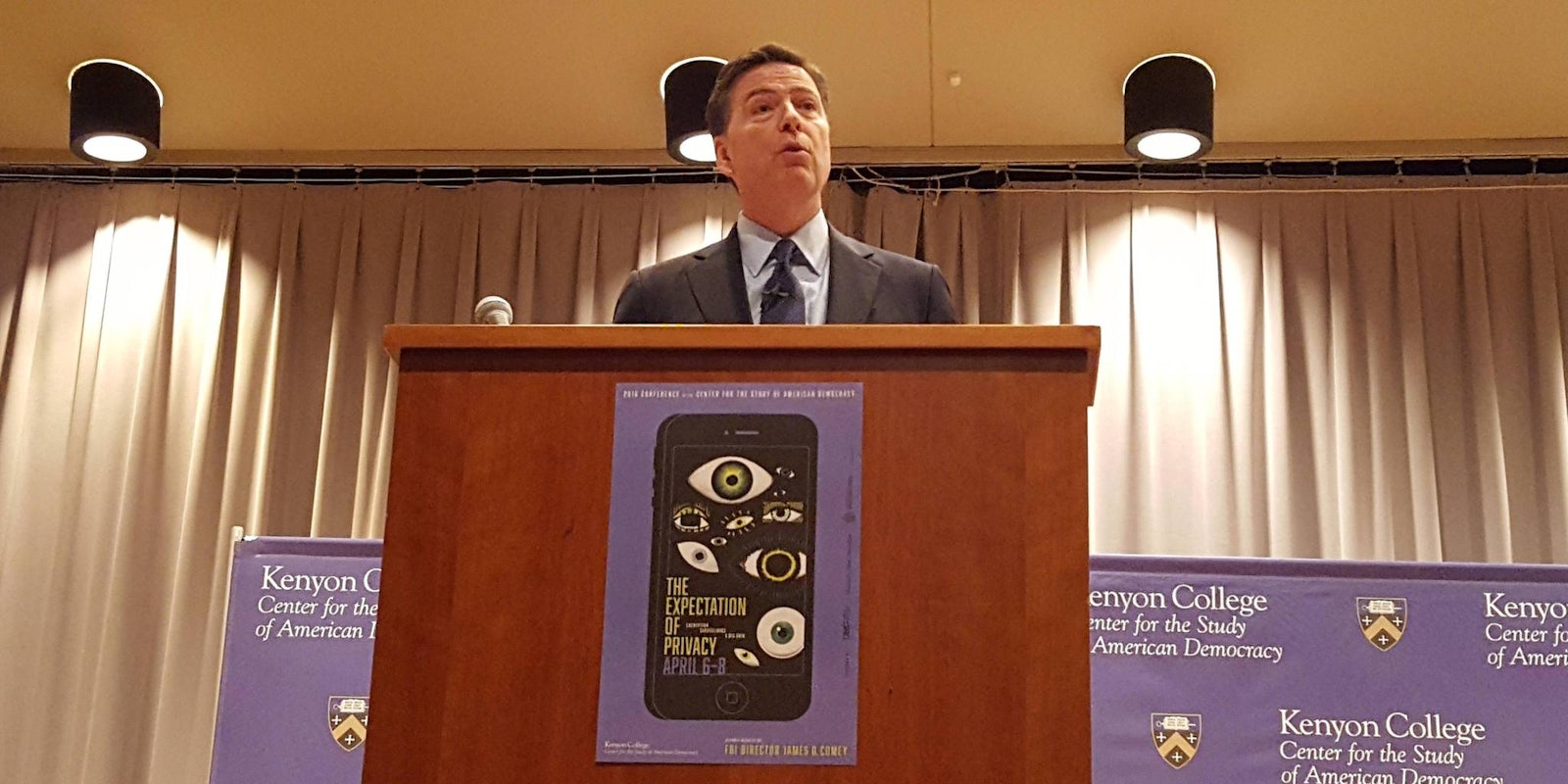

FBI Director James Comey implored Americans to avoid talking points and grapple with the real trade-offs of the roiling encryption debate in a speech Wednesday night at a conference on privacy and security.

“I love strong encryption. It protects us in so many ways from bad people,” Comey said at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, during a keynote address for the school’s biennial political-science conference. “But it takes us to a place—absolute privacy—that we have not been to before.”

Comey’s agency spent half of February and most of March embroiled in a legal battle with Apple over access to the locked iPhone of a dead terrorist, a highly publicized dispute that turned decades of competing privacy and security claims into a mainstream news event.

“No matter how you feel about it,” Comey said of the changing technological landscape, “you have to acknowledge there are costs to this new world.”

The Justice Department won a court order on Feb. 16 directing Apple to write custom software that would help the Federal Bureau of Investigation access the iPhone of Syed Farook, who, with his wife, killed 14 people and wounded 22 others in San Bernardino, California, last December. Apple objected, arguing that its compliance with the order—issued under the 1789 All Writs Act—would empower the government to demand increasingly broad and intrusive forms of assistance, jeopardizing its customers’ privacy and security.

“No matter how you feel about it, you have to acknowledge there are costs to this new world.”

The San Bernardino iPhone fight, which the Justice Department abandoned on March 28 after receiving outside assistance unlocking the phone, immediately became a symbol of a broader debate about whether tech companies should configure their encryption so that they can bypass it in order to provide investigators with user data.

Senior officials like Comey argue that tech firms have a responsibility to comply with lawfully issued warrants for such data, and they argue that, by implementing unbreakable encryption, these firms are aiding criminals and terrorists who are “going dark” on their platforms.

But Silicon Valley executives, security experts, cryptographers, civil-liberties organizations, and some former national-security officials argue that so-called “backdoors” in commercial encryption are unnecessary, ineffective, and dangerous.

Opponents of backdoors point out that hackers will inevitably find these holes, rendering consumer technology newly vulnerable on an unprecedented scale. They also argue that the prevalence of foreign-made encrypted devices and services would render a U.S. backdoor mandate pointless, because criminals would simply migrate to platforms not covered by the law. They further note that demanding weakened encryption would kneecap American tech companies’ economic competitiveness, which has already been strained by the 2013 Edward Snowden revelations about their voluntary and coerced partnerships with U.S. intelligence agencies.

But in an interview with the Daily Dot ahead of his speech, Comey rejected the notion that guaranteeing the government’s ability to access encrypted data required adding vulnerabilities to encryption code.

“I think it’s a bit of a false premise to say that the only answer to the challenge we face is to introduce vulnerabilities into code,” Comey told the Daily Dot, before adding, “I’ll leave that to experts.”

Comey suggested that tech companies’ features and services that do not offer unbreakable encryption means they could weaken the security of other products that currently include this technology.

“Today, Apple encrypts the iCloud but decrypts it in response to court orders,” he said. “So are they materially insecure because of that?”

Comey later reiterated this point, saying, “I see Apple today encrypting the iCloud and decrypting it in response to court orders. Is there a hole in their code?”

But Comey’s iCloud argument did not address a central fact: that the current debate is about whether companies should be allowed to progress beyond the level of encryption protecting iCloud.

Asked about the danger of pushing people to foreign platforms by limiting U.S. encryption, Comey seemed to suggest that the answer was to regulate encryption worldwide. “Every country that cares about the rule of law cares about this,” he said. “I think whatever we come up with—we as a people that care about these issues, in and out of government—it has to have some international component to it.”

He added that officials did not want to “chase innovation out of the United States and other places.”

Several Obama administration officials have also sounded the alarm about backdoors. Edith Ramirez, the chairwoman of the Federal Trade Commission, warned that requiring them would damage customers’ privacy and security. Ashton Carter, the secretary of defense, forcefully defended unbreakable encryption and said that the Pentagon, which is constantly under digital assault from rogue hackers and enemy nations, considered strong data security “an absolute necessity.”

“The notion that privacy should be absolute, to me just makes no sense given our history and our values.”

Comey said he didn’t see those remarks as undermining his drive to guarantee lawful access to encrypted data. And in a remark that highlighted why he and his critics might be talking past each other, Comey said that he didn’t like the term “backdoor” because it suggested a desire for “some access to your device or to your server,” which he said he didn’t want.

In his address to the Kenyon community, Comey touched briefly on the matter of the third-party exploit that let the FBI access the San Bernardino shooter’s phone, public details of which remain sparse. He said he was fairly familiar with the company that provided the exploit and that he had high confidence in the company’s ability to protect the secret, which will now be sought by hackers worldwide. Comey declined to go into detail about how the bureau would decide when to help local police access other iPhones using the tool the government bought, saying, “We’re trying to sort that out now.”

Even as Comey warned against embracing emotional arguments about encryption, he also predicted that “at some point,” encryption would “figure in a major tragedy in this country.” His overarching goal, he said, was to get people talking about the trade-offs before that happened.

“The notion that privacy should be absolute,” he told the crowd, “to me just makes no sense given our history and our values.”