In late 2003, several months before Mark Zuckerberg captured the attention of Harvard University—and later the world—with Facebook, another college student was working on his own online social network.

WhoUp, created by University of Chicago undergrad Aris Michalopoulos, targeted college students. Like Zuckerberg, Michalopoulos wanted to win the social war before it had even really begun.

Of course, there’s a good chance you’re reading this article after clicking a link on Facebook. And that tells the rest of the story. Facebook went on to become the world’s largest social network—boasting more than a billion users today. As for WhoUp? The domain is now yours to buy on GoDaddy.

For the longest time, it appeared as if Michalopoulos had given up the social dream, moving on to a career in finance. But try as he might, he was never fully able to expel the ambition from his mind.

Now Michalopoulos is jumping back into the game. He’s got the lessons and scars of WhoUp to guide him this time, but the landscape of social media has changed dramatically from the halcyon days of 2003. It’s a cluttered field of networks striving to breakaway from the pack. Facebook is still the social superpower, but an ever increasing number of sites and mobile apps like Tumblr, Pinterest and Instagram are racing to fill every niche angle.

It’s from this cacophony that Michalopoulos draws his latest inspiration. With Empeopled, he hopes to cut through the noise of other social networks, allowing the best content and ideas to rise to the top. Encouraging users to strive for influence rather than simple attention, Michalopoulos is not just looking to build a new startup. He wants to change the way we interact on the Web.

Climbing the Social Ladder

By 2008, WhoUp was a fading memory for Michalopoulus. Aside from his involvement in a phone-bumping app, he was primarily focused on earning a comfortable living as a portfolio manager for a Chicago-based hedge fund.

But then came the Great Recession and a financial crash that threw the entire world into a panic. Michalopoulos watched aghast as social media became a platform for what he saw as bad financial and policy advice, with everyone positioning themselves as economic experts regardless of qualifications.

“It was a story of frustration,” he says. “I had a front row seat for this economic armageddon and all the political incompetence that came with it.”

From that moment onward, Michalopoulos was obsessed with the idea of creating a social network that valued credibility and rewarded expertise. By 2011, he was so committed to the idea that he left his comfortable job to focus on the project full-time. He spent most of the first year developing a business plan and doing a lot of background research (an effort to avoid WhoUp’s mistakes). In 2012, the company hired its first programmers. Ultimately, it would take nearly four years from the initial light bulb in Michalopoulos’ head to the first-round of closed beta testing. During that time, the project was financed almost exclusively mostly by Michalopoulos himself, his partners, and some donations from friends and family.

It was a long gestation period. Michalopoulos was trying to incorporate the lessons he’d learned from WhoUp’s failure. He realized that nurturing and growing a community is just as important as crafting the technical architecture that supports it.

The end result of this years-long development process was Empeopled, a site that encourages users to make a long-term investment and climb a steep social ladder in order to earn real clout on the network.

Virtual citizens, virtual societies

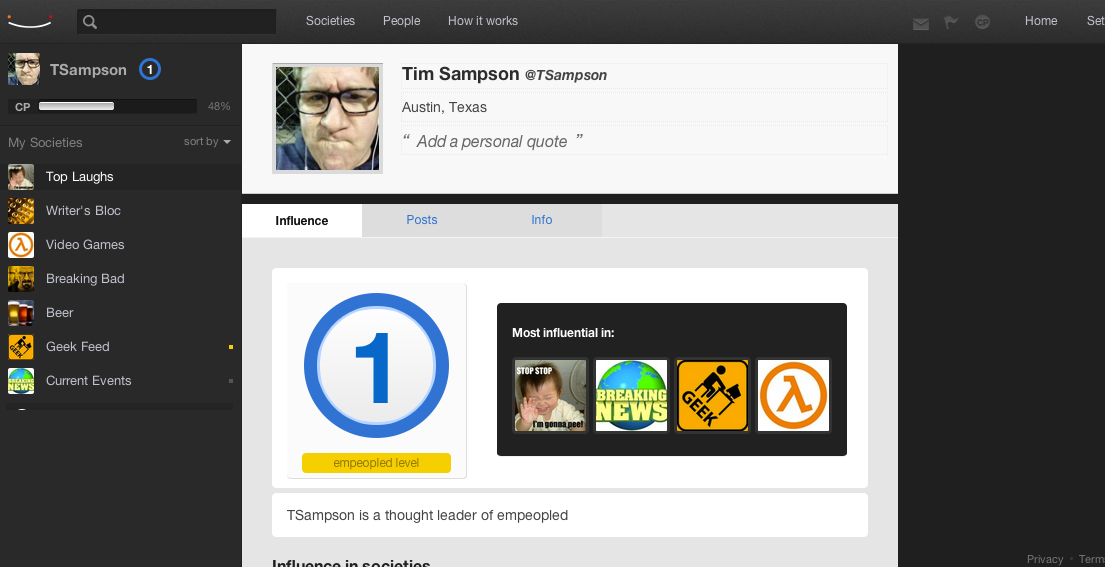

When a new user first sign’s on to Empeople,d they are assigned a number: one. Essentially, this is a score, called your “citizen level,” that gauges your level of influence on the site. The higher the number, the more influence you have. It’s a scheme of stratification that’s intended to keep trolls and shallow attention-seekers at bay.

As in a role-playing game, you can increase your level by completing various tasks. Engaging in conversations, posting items, and getting upvotes all push you towards bumping up that number. It’s an arduous process to increase your site-wide citizen level, but users can rise fairly quickly within defined content groups—known as societies. For instance, though my site-wide citizen level is still a one, my level within the “Top Laughs” society rose to three with a single posting and some positive upvotes.

My empeopled page, showing a citizen level of “1.”

These numbers and levels may sound arbitrary, but they serve an important purpose on the site.

Similar to social news site Reddit, Empeopled—in its current state—works primarily as a content aggregator, connecting users with images, articles and videos from across the Web. The site has a comparable upvote/downvote feature. But the key difference from Reddit is the apportionment of votes, which are proportionate based on citizen levels in a certain society. So a level three citizen, like me in the Top Laughs society, has a vote that counts as three. Another user with a citizen level of 12 would have a vote four times as influential as mine. That’s unlike Reddit, where one user gets one vote no matter where it’s placed, or what their background is.

The prospect of climbing such a regimented social ladder might be daunting for users who are used to a social network that asks “What’s on your mind?”—as if you’re the only one they’re asking. But Michalopoulos is striving for a social meritocracy where the best thoughts and content are rewarded with greater prominence. He wants a peer-review system where reasoned opinion, not blind clicks and mass popularity, determine what gets showcased.

“I’m amazed at the sheer number and breadth of interesting articles on the site,” says Nicholas Stephanopoulos, an early adopter of Empeopled. “The voting/ranking mechanic is highly useful, and articles that have a lot of upvotes are consistently interesting and worth reading.” Stephanopoulos, it’s worth pointing out, is one of Michalopoulos’s friends.

Indeed, it’s important to note the site only has 1,600 registered users and is still in beta testing. Though on a small scale the site to be conforming with Michalopoulos’ vision of a utopian social network where ideas are king, there is no way to tell what might happen as the site grows.

As with many would-be utopias, it’s easy to imagine the dystopian flip-sides. The site could become a nightmare version of Reddit where karma actually matters and those with the most karma (or citizen levels in this case) are able to assume dictatorial power over certain societies. Though Michalopoulos wants the site to reward competence, even he can’t guarantee that will be the case.

“We can’t claim the system will reward expertise,” he said. “It rewards influence. The idea is people will reward the voices they want to listen too.”

Michalopoulos hopes that goes hand-in-hand with actual expertise in a given area, but he concedes it is still possible for a “Reddit-style disintegration” into “popularity contests” in some societies. He insists, however that there are several safeguards built into the site to prevent a downward spiral of the entire network.

The biggest? Unlike Reddit, the site has no “frontpage,” where everyone is competing for the same finite amount of space. Indeed, posts flow via a newsfeed, similar to Twitter or Tumblr. Also, users have greater latitude to alter the site and deal with those who would attempt to dominate a society. Societies regularly elect leaders and establish their own rules.

If a society were to be taken over by unpopular leaders, Michalopoulos suggests users could create a replacement society, where they can set up their own ruels. A society could even establish strict membership rules that actually dictate a degree of verifiable expertise in an area before joining.

This self-governance plays into Michalopoulos’ bigger plans. He not just looking to create another content aggregator. He hopes the site will become a far-reaching tool that allows for massive organizational undertakings that can spread ideas and movements offline. He hopes the site’s democratic societies will start behaving more like groups offline, unlocking the Web’s full potential.

“My goal is to help people organize themselves for more useful purposes,” Michalopoulos said. “Right now it’s just conversation, but there is the potential for much more.”

Photo via Aris Michalopoulos