Emoji and emoticons are often confused for being the same thing. Here’s a newsflash for you: They’re not.

Even though emoticons predate emoji by almost 20 years, it’s easy to see why people mix them up. They sound similar and serve essentially the same purpose. Emoji and emoticons both act as visual cues in everyday life on the internet when the written word just doesn’t cut it.

If asked to weigh in on the difference between emoji and emoticons, most human beings are likely to have this reaction:

¯_(ツ)_/¯

But turns out there is a difference–and it isn’t just mere semantics. For those who aren’t familiar, the series of symbols above is known the shruggie emoticon. Not the shruggie emoji. Unlike emoji, emoticons are typed using the keyboard on your phone or computer. Emoji, on the other hand, are images that are encoded in Unicode Standard.

With the launch of 72 new emojis in Wednesday’s update of Unicode 9.0, the closest thing we have to a shruggie emoji is this:

Think of emoticons as the older, less tech-savvy Western cousin of the emoji. The usage of emoticons outdate Facebook, the iPhone, and even Taylor Swift. You may remember the golden age of emoticons, during the days of AOL Instant Messenger, email and SMS text plans that charge by the word. But emoticons have been around for far longer.

According to the Guardian, the origin of emoticons dates back to September 1982, when a computer scientist named Scott Fahlman. Fahlman posted on the Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) message board that :-) and :-( could be used to distinguish jokes from serious statements online.

Here’s the message that Fahlman posted below, as per CMU:

19-Sep-82 11:44 Scott E Fahlman :-)

From: Scott E Fahlman <Fahlman at Cmu-20c>

I propose that the following character sequence for joke markers:

:-)

Read it sideways. Actually, it is probably more economical to mark

things that are NOT jokes, given current trends. For this, use

:-(

You can read the entire thread from the CMU message board here.

Read more from the Daily Dot:

The first appearance of the term “emoticon” in the New York Times is in a Jan. 28, 1990 story on the first Internet bulletin boards. The story includes a helpful glossary of terms such as “lurker” (“one who reads postings but never responds”) and “flame” (“to post a particularly irate message”).

Here’s what the Times settled on for its definition of “emoticon”:

Emoticon – typographical device used to indicate tone or emotion in a posting. Most of the devices, which are viewed sideways, are based on the smiley face – :-). Flirting is expressed with a raised eyebrow -;-). Drunkenness with the typographical equivalent of a radiant, bulbous nose – :*).

It’s highly possible the emoticon was invented centuries before Internet message boards or even computers. Typewriters, after all, date back to before the Civil War era. Who’s to say that Fahlman, and not some bored 19th-century secretary, was the first to realize that a colon and a parentheses, when paired together, look an awful lot like a sideways smiley face?

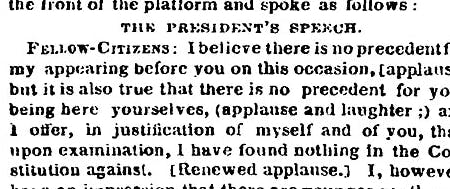

One historical newspaper specialist told the New York Times he believed he found evidence of a ;) smiling wink emoticon in an 1862 transcript of a speech by President Abraham Lincoln, which you can see below:

Over the past five years, the usage of emoticons has largely been replaced by emoji. Emoji originated in Japan in the late ’90s, explicitly for usage in cellphones. The inventor of emoji is one Shigetaka Kurita, who explained to Ignition the space limitation on the LCD screens of cellphones at the time—around 48 characters—ended up being a huge communication barrier. Japanese TV weather forecasts were texting users the word “fine” to describe a sunny day.

Kurita told Ignition that he found this difficult to understand, especially since Japanese weather forecasts typically contained symbols of suns or clouds to describe the weather. “I’d rather see a picture of the sun, instead of a text saying ‘fine,’” Kurita said.

Kurita, who was working on team that was developing Japan’s first mobile internet platform for a mobile service provide, pitched the idea of emoji to his superiors. They loved it. And the rest is history.

How did a Unicode series of images with Japanese roots trump the American-born ASCII emoticon? Anyone who’s tried to type out an eggplant emoticon knows the answer to that question. Emoji simply takes less effort and time to produce. As social media evolves to become more visual and image-heavy, emoji has emerged as the colorful, modern equivalent to the black-and-white emoticon. The vast number of emoji (there are currently 1,851 different emoji, according to Emojipedia) cover everything from food to sports to human relationships and offer endless opportunities for expression.

The New York Times attributed the rise of emoji in the West to the rise of the iPhone and iOS 5, which included a library of pre-installed emoji.

Wrote the Times:

But unlike emoticons, emoji don’t require tilting your head sideways to make sense of the image. They are a kind of pictorial alphabet stored on a phone that can be displayed in place of the regular keyboard, making it easy to tap out a visual message.

The ’90s-era limits on space and time are gone in digital communications, but emoji appear to be here to stay.