Emoji are becoming more complicated. The bubbly little smileys and cartoon images originally associated with Japanese culture have become a language, picking up quirks and localizations along the way.

Generally speaking, they convey ideas or emotions and do so in a cute, inoffensive manner. Even when they are risque or dirty, the simplistic art means they come with a certain charm. It’s like a little kid picking up on a swear word without realizing the meaning.

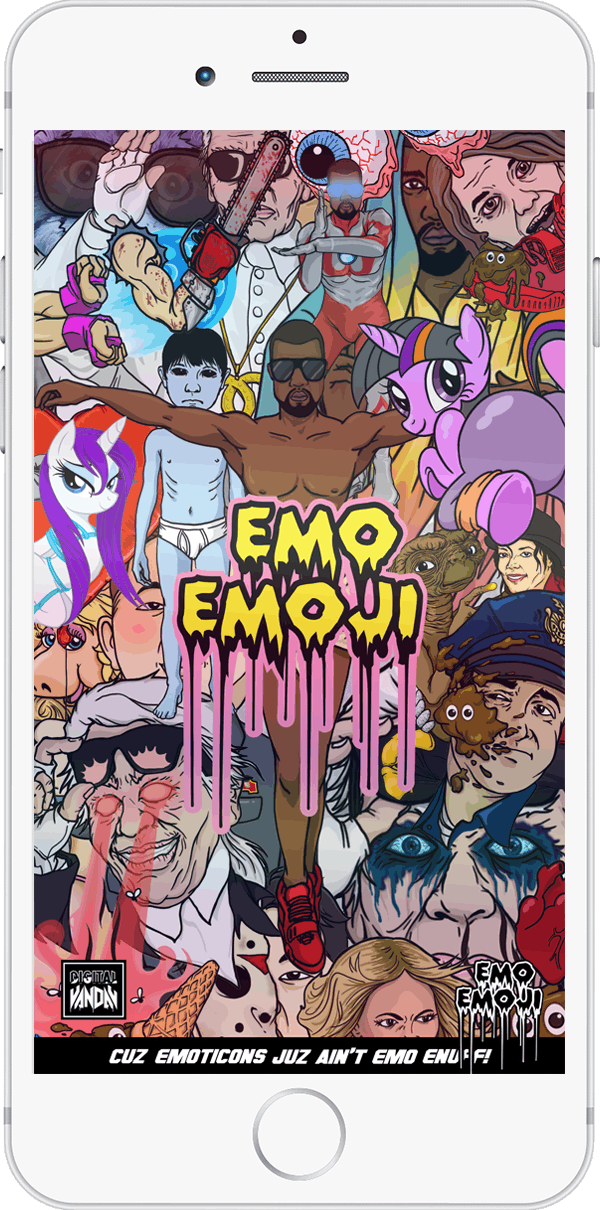

But that innocence is nowhere to be found in Emo-Emoji.

The brainchild of Le Messie, most noteworthy for his work with Lupe Fiasco, Emo-Emoji are the rebellious teenage years of digital communication.

I was first pitched on Emo-Emoji during the madness of the Sony hack, while fingers were still being pointed wildy, mostly landing on North Korea because of the depicted death of the country’s leader in the Interview.

The set of stickers were heavy on imagery surrounding the film and Kim Jong-un, including him riding a tandem bike with Dennis Rodman. Another shows Seth Rogen dressed as the dictator with James Franco holding a gun to his head.

They were, for the most part, harmless, if not a little crude. These emoji were so pop culture-focused that their relevance has been dwindling more and more every day. A Kim Kardashian “#BreakTheInternet” parody with a My Little Pony character, Kim Jong-un as Psy smashing a PlayStation 4 with the Gangnam Style dance—hell, there was even a Borat emoji. The stickers had about as much cultural currency as a cutaway joke on Family Guy.

But in the lampooning there was one sticker that didn’t sit right.

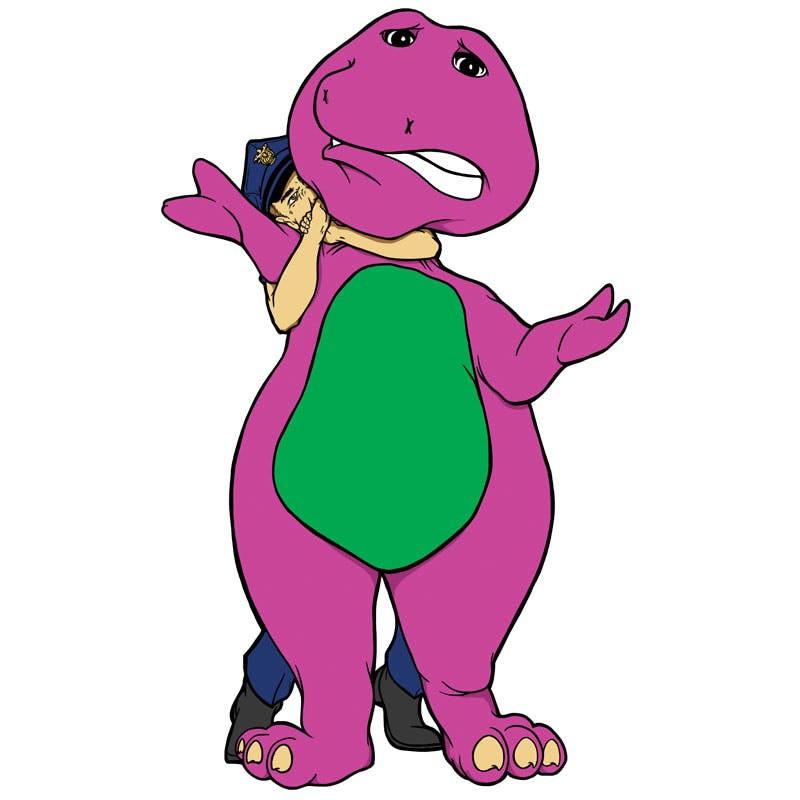

It depicted Barney, the big purple dinosaur that has been a part of everyone’s childhood for the last two decades, detained in a choke hold by a police officer. It wasn’t hard to figure out what the image was meant to portray, though the file name “I Can’t Breathe Barney” did away with any ambiguity.

The first thing I thought, the first thing my colleagues thought, the first thing that everyone I showed it to thought was “that’s extremely offensive.” It just felt wrong and insensitive and entirely inappropriate. It felt like it was making light of a dire situation and was exploiting the wrongful death of Eric Garner.

Part of that is the context of the image, and part of it is the context of where it’s being seen. If “I Can’t Breathe Barney” was tagged with krylon on the side of a brick building, there probably would be no double take or second guessing. Street art has grittiness to it that matches its environment, so it’s not unexpected for it to have some bite.

To see that type of imagery cleaned up, polished, and placed against the fluorescent white background of an iMessage screen makes it jarring. It’s hard to imagine it between the text bubbles of dinner plans and “OMGs” without it feeling out of place. There aren’t a lot of opportunities to share that image in conversation other than to say, “Want to see something messed up?”

“Just like Banksy’s works on concrete can relay a word or an array of words and meanings, my digital stickers do the same.”

Le Messie understands this as well as anybody. In the press release for Emo-Emoji, he’s quoted as saying, “We’re going to be as edgy as we can get away with under Apple.” He also understands the relationship between the digital and physical realm: The more shares an emoji gets through the Emo-Emoji app, the more likely his company will produce a physical sticker or T-shirt or hat or skate deck with that image on it.

That doesn’t make it any less difficult to deal with. Instead of just an insensitive collection of pixels, it becomes a physical product to profit off of. That’s always a tough space for artists, walking the line between art and commerce, but the image invoking Eric Garner muddles it further because it feels exploitive.

When I asked Le Messie about the Barney sticker in particular, he explained, “With the ‘Barney Breathe’ sticker I wanted to portray a big character that would relay Eric Garner’s characteristics of being a gentle giant. The color of Barney plays a large factor in this sticker piece as well. ‘Just because I’m a big purple T-Rex dinosaur, it doesn’t mean I’ll eat you… Give me a chance to breathe, then lets talk calmly in a controlled environment.’

“Just like Banksy’s works on concrete can relay a word or an array of words and meanings, my digital stickers do the same,” he continued. “In today’s culture, like the meme, the stickers sometimes have double and triple meanings, it depends in which context they are used.”

Of course brevity isn’t always the best method for such challenging conversations; Twitter has proven this time and time again. In emoji’s case, the adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” isn’t always true.

But if an emoji can start those worse, then maybe that counts for something? Le Messie is confident that his emoji will stick and that people who need to understand them will. “The youth today are extremely subliminal in the way they converse through digital and social media, puns and hidden meanings. These forms of communication are all a part of the cool way they portray their slang and character over the internet. I see Emo-Emoji as the evolution of the emoji, because emoji just aren’t emotional enough,” he said.

Emo-Emoji definitely strike more of an emotional chord than your standard smiley face. Whether that’s a positive thing remains uncertain.

Following the deadly attack on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, the subject of free speech is being hotly debated. In the wake of the tragedy, in which “controversial” artists were needlessly attacked and killed, made martyrs for free speech, we’re likely due for a reminder that being offensive does not make something more virtuous by default.

Hopefully if “I Can’t Breathe Barney” pops up in a chat, it’s followed by many text boxes discussing the topic with more nuance and understanding.

Photo via Emo-Emoji