Edward Snowden is the world’s most wanted man. He faces charges related to espionage and theft of government property for leaking classified NSA documents to journalists. He is actively evading U.S. law enforcement by living under asylum in Russia.

So, can he still vote in the 2016 election?

Absolutely, yes, according to Ben Wizner, leading U.S. attorney for Snowden and director of the Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project at the American Civil Liberties Union.

“There’s no legal basis whatsoever for depriving Edward Snowden of the right to vote.”

“The short answer is: He’s eligible,” Wizner told the Daily Dot when asked about Snowden’s voter status. “There’s no legal basis whatsoever for depriving Edward Snowden of the right to vote. He’s been convicted of no crime, much less one that would strip him of his civil rights.”

Two and a half years after his leak of secret National Security Agency documents, Snowden remains at the center of the ongoing debate over the balance between civil liberties and security. Whoever becomes the next president of the United States must grapple with this issue in a post-Snowden world, making his ability to actually vote for his candidate of choice all that more important, if only symbolically.

“He has every much right to vote as any other American citizen,” added Wizner, who took on Snowden’s case shortly after the North Carolina native turned 30 and became stranded in the transit zone of Moscow airport.

Snowden’s Timeline

Before absconding to Hong Kong in May 2013, Snowden rented a three-bedroom house in the Waipahu community of Oahu. He had arrived on Hawaii’s most populous island in March 2012, after accepting a technologist position with Dell, a leading U.S. government contractor.

To vote in Hawaii, Snowden need only be registered and considered a resident of the state. (His attorney declined to confirm his residency status.) Without a conviction, the charges against him, which carry a penalty of up to 30 years in prison, have no bearing on his voter eligibility.

“I’m not aware of any state that disenfranchise people accused of crimes,” said Richard Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine. “If he did not renounce his citizenship and intends to return to Hawaii, my guess is he could request an absentee ballot. But again, it is a matter of state law.”

Voter disenfranchisement

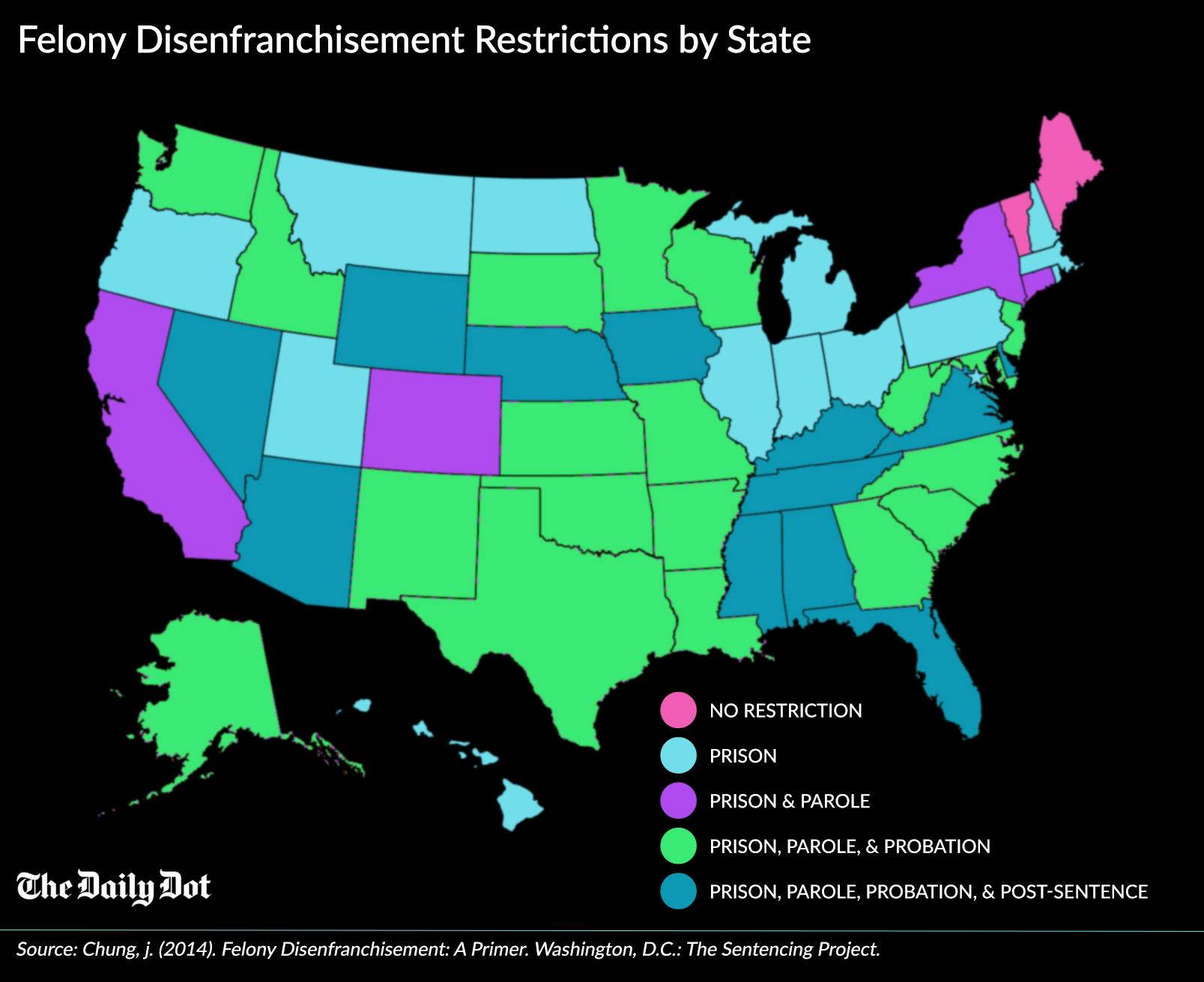

With regards to voting, Hawaii has some of the most relaxed laws in the country. Voting rights can only be suspended while a convicted felon is serving prison time. Even while on parole or probation, a released felon can participate in an election by re-registering with the state’s election office at a minimum of seven days in advance.

Only in Maine and Vermont are the laws more laid back, permitting convicted felons to complete absentee ballots from behind bars.

At the other end of the spectrum, 11 states—Alabama, Arizona, Delaware, Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nevada, Tennessee, Virginia, Wyoming—reserve the right to permanently strip residents of the vote due to past crimes.

And in eight U.S. states—Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, South Carolina, and South Dakota—being incarcerated for a low-level misdemeanor means a suspension of voting rights.

With the world’s most populous prison system, America’s felony disenfranchisement significantly reduces the number of votes on election day. An estimated 5.85 million Americans will be denied the right to vote in the 2016 presidential elections due to a criminal record, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, disproportionately affecting racial and ethnic minorities who now make up 60 percent of the U.S. prison population.

Of the 2.2 million Americans incarcerated, more than 200,000 are under the federal government’s control. As of Sept. 30, 2014, 50 percent of them were serving time for drug offenses.

Even more striking is that, while only making up one-third of the population, two-thirds of all incarcerated drug offenders are people of color, despite research showing white Americans consume illicit drugs at a far greater rate than their minority counterparts.

According to the Sentencing Project, one of every 13 African-Americans will be ineligible to vote in the upcoming election.

Illustration by Max Fleishman