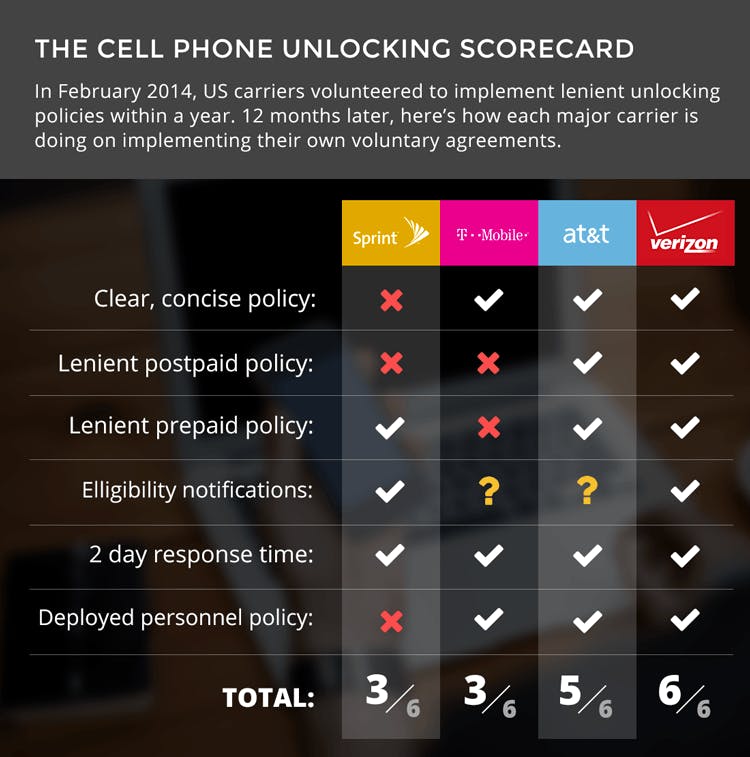

A year ago, U.S. cell carriers agreed to implement more lenient unlocking policies. I compared what they committed to do with what they actually did. Here are the results:

Summary:

-

Sprint and T-Mobile have failed to fulfill half their own voluntary commitments.

-

Verizon has the most lenient policy: it’s almost entirely stopped locking its devices. But that may only be because the FCC required it.

-

AT&T has met almost all its unlocking commitments.

-

The voluntary measures are missing a critical criteria: interoperability.

-

Third-party unlocking is still critical. Long overdue reform of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)’s anti-circumvention law is the only way to protect a consumer’s right to unlock.

The “Voluntary Agreement”

Back in December 2013, the wireless industry association CTIA wrote a letter to the Federal Communication Commission. In it, the trade group announced that all four of the country’s major carriers—AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon—had committed to adopting six voluntary measures to make unlocking cellphones easier for consumers.

That “voluntary” agreement came at the last minute, after months of pressure from the FCC. In late 2012, the Librarian of Congress had removed an exemption from the DMCA for cellphone unlocking. Consumers were appalled. Without an exemption for using third-party software to unlock devices, the only way to break phones and tablets free from carriers’ software locks was by asking the carriers themselves. Trying to negotiate anything with a wireless carrier’s support center is infuriating, let alone an unlock code.

President Obama spoke out for the need for better unlocking practices, and the FCC threatened to impose new regulations on the carriers. But FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler gave the carriers an out: If they were able to commit to voluntarily improve their policies by the end of 2013, he wouldn’t push for regulation. So on Dec. 13, just a few weeks shy of Wheeler’s deadline, the carriers came up with their six voluntary unlocking principles and promised to implement them within a year.

Earlier this week, the FCC announced that it was “proud to report that the country’s major providers have met their commitment.” I’ve spent much of the last two years advocating for the right to unlock and modify devices (cellular or otherwise), so I was particularly curious to check out exactly how each carrier has implemented the principles set out in the CTIA’s Consumer Code for Wireless Service.

Here’s what the carriers promised:

Disclosure

Each carrier should post clear, concise and accessible policies for how they’ll handle unlocking postpaid and prepaid devices.

Postpaid policy

Postpaid customer’s phones should be unlocked by carriers for:

-

their customers

-

former customers with accounts in good standing

-

individual owners of eligible devices,

If either:

-

their contract has ended,

-

their device financing plan has been completed,

-

or an early termination fee has been paid.

Prepaid policy

Prepaid phones should be unlocked no later than one year after initial activation, as long as “reasonable time, payment or usage requirements” are met.

Notification

Carriers should notify customers that their devices are eligible for unlocking or automatically unlock users’ devices once they’re eligible for a free unlock. For prepaid customers, that notice can occur at the point of sale or via a notice on the website.

Response time

Carriers should unlock devices within two days of receiving a request, or at least send a request to the OEM within two days, or explain why the device can’t be unlocked or they might need more time.

Deployed personnel

Carriers should unlock devices for deployed military personnel who are customers in good standing, as long as they show deployment papers.

What’s missing: interoperability

The most significant missing component from the “Consumer Code” is a commitment from carriers to accept unlocked devices on their networks.

Interoperability is an obvious and critical piece of what makes unlocking valuable. If you unlock your phone, you need to be able to take it to another carrier and use it. Sure, in some cases, the technologies differ (for example CDMA vs GSM), but with the rollout of LTE and modern smartphones with mutli-band, multi-technology support, including the iPhone, that’s a decreasingly common barrier.

But many carriers, most notably Sprint, specifically says that it won’t activate phones that were originally sold by another carrier. That’s despite the cellular technologies the phones use being entirely standardized.

In Sprint’s case, those restrictions even apply to Virgin Mobile devices, which run entirely on Sprint’s network. Even if Virgin Mobile unlocks your phone for you, Sprint won’t activate it for use on a prepaid or postpaid account. It’s patently absurd: There’s simply no good reason to prevent users from bringing their own devices—in fact, it makes it even harder for consumers to switch to your carrier. The only justification for that kind of policy is to gouge customers and force them to buy more expensive, “carrier-approved” devices that come with 2-year contracts.

Verizon is the only carrier that seems to have realized how ridiculous it is to “lock” consumers’ devices in the first place. It’s largely stopped the practice, though to be fair, the company apparently was required by the FCC to do so when it bought licenses in the 700MHz Block C auction.

But even Verizon doesn’t make interoperability simple. Its Bring Your Own Device program, for instance, makes it clear that your phone needs to be an “unused Verizon phone” to be eligible.

Reforming the DMCA is still critical

It’s worth taking a step back and examining the absurdity of these locks. If you’ve paid for your AT&T phone, committed to a 2-year contract, and agreed to an “early termination fee,” what purpose does a lock really serve? If you’ve paid cash to purchase a prepaid device, why should it come locked to just one carrier?

There’s plenty of evidence that locks serve little real commercial purpose. Verizon’s business hasn’t suffered since it stopped locking its phones. Countries like China and Israel have made locking devices outright illegal with no harm to their wireless industries and plenty of gain for consumers. But unfortunately, it’s unlikely that Congress or the FCC will take action to implement a similar policy here in the U.S.

That’s exactly why the right to unlock and modify electronics is critical. Corporations may be able to sell us locked-down devices, but consumers should at least have the right to take action and circumvent those locks as they see fit.

Unfortunately, a shortsighted and clumsy provision of the DMCA can make it completely illegal for consumers to modify the devices, software and content they purchase.

The DMCA’s anti-circumvention provision was a shortsighted law, written under pressure from the content industry in 1998, ostensibly with the goal of preventing piracy. It includes a problematic legal loophole: It can make it a crime, punishable by 5 years of jail and $500,000 in fines, for circumventing a “technological protection measure,” even if there’s absolutely no copyright infringement.

Courts have tried to strike down that interpretation of the DMCA, but there’s still no clear legal precedent. As a result, the DMCA has been used to threaten software developers, consumers, and security researchers, as well as to harass authors of unlocking software.

Though Congress passed a bill in August of last year to reinstate a temporary exemption to the DMCA for unlocking, that measure will only last until later this year. As it stands, we may well lose our right to unlock our devices without carrier permission when the Librarian of Congress announces the results of the rulemaking in a few months time.

There’s a simple and easy fix to all this. Congress could pass a bill clearly stating that it’s not illegal to circumvent a lock as long as there’s no intention of copyright infringement. That’s exactly what the Unlocking Technology Act would have achieved if it were passed back in 2013. But as is often the case in Congress, the bill was stalled due to opposition from special interests.

It remains to be seen whether Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), the chair of the House Judiciary Committee, will include anti-circumvention reform in his current review of U.S. copyright laws. If you’ve made it this far, take a moment and tweet at him to ask him to take action and protect your right to remix and repair.

How we scored the carriers

We studied each unlocking policy to check how it compared with the CTIA’s Consumer Code. Here’s our full rundown:

AT&T

-

Disclosure: AT&T provides clear instructions online at this URL.

-

Postpaid policy: AT&T will unlock postpaid phones for its own customers whose phones have been active for at least 60 days. It’ll also unlock devices for past customers, and for people who bought a second-hand device, as long as the phone is not stolen or actively being used on someone else’s account.

-

Prepaid policy: Prepaid AT&T devices will be unlocked as long as they have been active for at least 60 days and have no unpaid balance.

-

Notification: We were unable to find any information about whether AT&T has implemented any notification system to let prepaid customers know of their unlocking eligibility. We spoke to two customer service representatives who gave conflicting accounts of how notifications might be delivered, and the official unlocking website was unclear.

-

Response time: AT&T says on this page that it will unlock phones within 2 business days.

-

Deployed personnel: AT&T will unlock phones and tablets as long as personnel provide proof of deployment. But AT&T claims it has “sole discretion” to limit the number of devices unlockable by military personnel, and it’s not clear what that number is.

Verizon

-

Disclosure: Verizon’s full unlocking policy is available here.

Verizon doesn’t lock any of its 4G LTE or 3G devices, other than its “Phone-in-the-Box” devices, which are trivially unlockable with either the code “000000” or “123456.” So we automatically gave them credit for all the other categories. Again, it was apparently required to do this.

Sprint

-

Disclosure: Sprint provides information about its unlocking policy online here. But those policies certainly can’t be described as “clear, concise and accessible.” The policy described on that page only applies to postpaid devices. The policy for prepaid devices, meanwhile, is hidden two links away, at this URL. A strange and artificial distinction is made between “domestic” and “international” unlocking, the latter of which is only available to current Sprint customers. The “domestic” unlocking category is again broken down into two subcategories: “Master Subsidy” and “Domestic SIM” unlocks.

-

Postpaid policy: Sprint’s postpaid unlocking policy breaks unlocking into two categories: one “for domestic usage” and another “for international travel.” Sprint says that it will only perform an “International SIM unlock” for active customers. There appears to be no provision for unlocking phones for international use if you are not an active Sprint customer, which is one of the requirements of the CTIA’s “Consumer Code.” Furthermore, it places restrictions on the number of devices you can unlock: For example, consumers don’t qualify for an “international” unlock if they’ve unlocked a different phone in the past 12 months.

-

Prepaid policy: Sprint says on this page that it will unlock a prepaid device if “[t]he device has been active on the associated account for at least 12 months with the account active at that time.” Though this is a bit confusing, the FAQ indicates that the company “may” unlock devices whose accounts are in good standing, even if the customer is not the original owner. We tentatively give Sprint the benefit of the doubt, even though the language it uses is very unclear.

-

Notification: Sprint says that it will “generally” notify postpaid users via SMS or a notice in their bill if they are eligible to have their device unlocked. Postpaid users are only notified via Sprint’s website.

-

Response time: Sprint doesn’t indicate how quickly it’ll process unlocks.

-

Deployed personnel: While Sprint claims that it “greatly appreciates the service that our U.S. military men and women provide at home and abroad,” its unlock policy has restrictions that don’t read that way. Specifically, it refuses phone unlocking for any personnel who has “previously unlocked another device within the past 12 months.” That’s well outside the voluntary guidelines of CTIA’s Consumer Code. What happens if a user’s phone or tablet is damaged or breaks while deployed?

T-Mobile

-

Disclosure: T-Mobile’s unlocking policies are described on this page.

-

Postpaid policy: T-Mobile will unlock postpaid devices but adds restrictions preventing consumers from unlocking more than two devices per line of service in a 12 month period. It also requires devices on its monthly plans to have been active for at least 40 days, even if the contract expires after a month under T-Mobile’s “uncarrier” policies and all dues have been paid. That requirement, that “the length of completed contract must be longer than 40 days,” violates CTIA’s Consumer Code, which states that consumers should be able to unlock any device once it’s out of contract.

-

Prepaid policy: T-Mobile will unlock prepaid devices, but strangely it requires that “[t]he [prepaid] account must not be canceled and in good standing.” That means if you buy a prepaid device, use it for a year then cancel your service, you can’t get your phone unlocked. The company also has a clause that “T-Mobile may request proof of purchase or additional information in its discretion.” It’s hardly clear-cut.

-

Notification: T-Mobile doesn’t indicate whether it’ll notify prepaid or postpaid customers of their unlock eligibility.

-

Response time: T-Mobile says it’ll provide unlock codes within two business days or provide further information about timing.

-

Deployed personnel: T-Mobile will unlock phones for deployed military personnel upon provision of deployment papers.

An earlier version of this post originally appeared at repeaterstore.com.

Photo via EvelynGiggles/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Fernando Alfonso III