In December, I deactivated my Facebook account and deleted the Messenger app from my phone. That’s when the texts started.

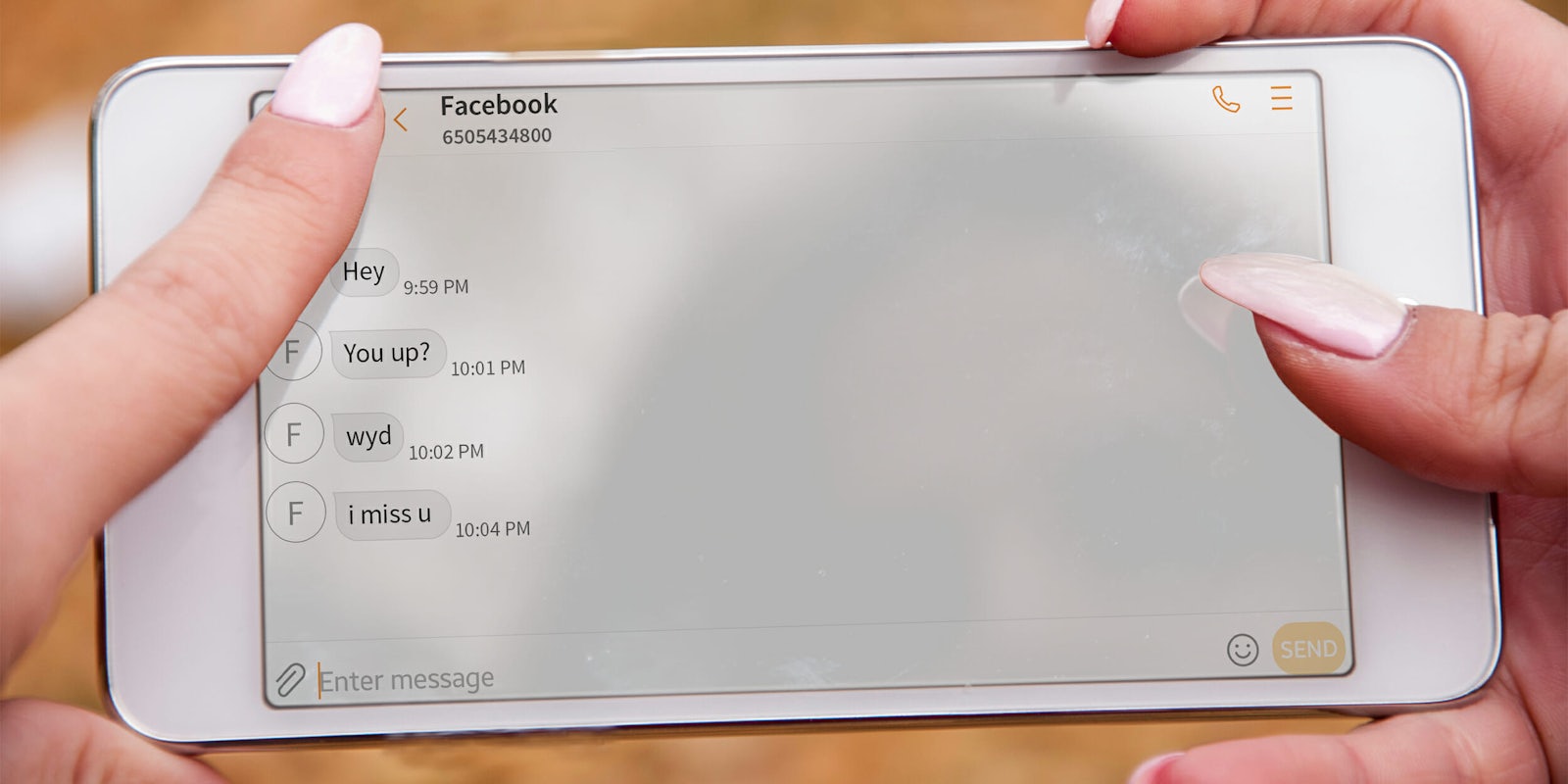

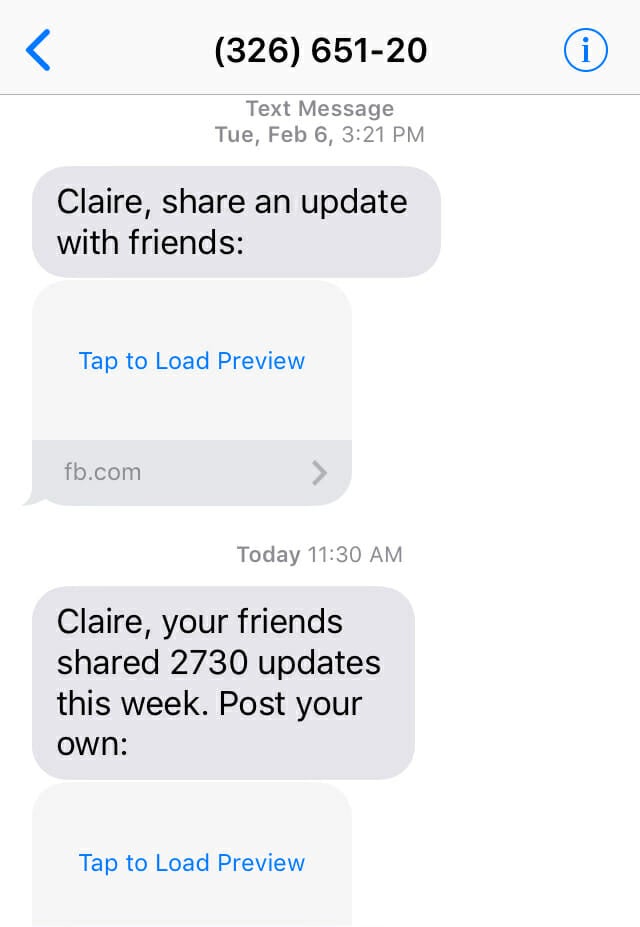

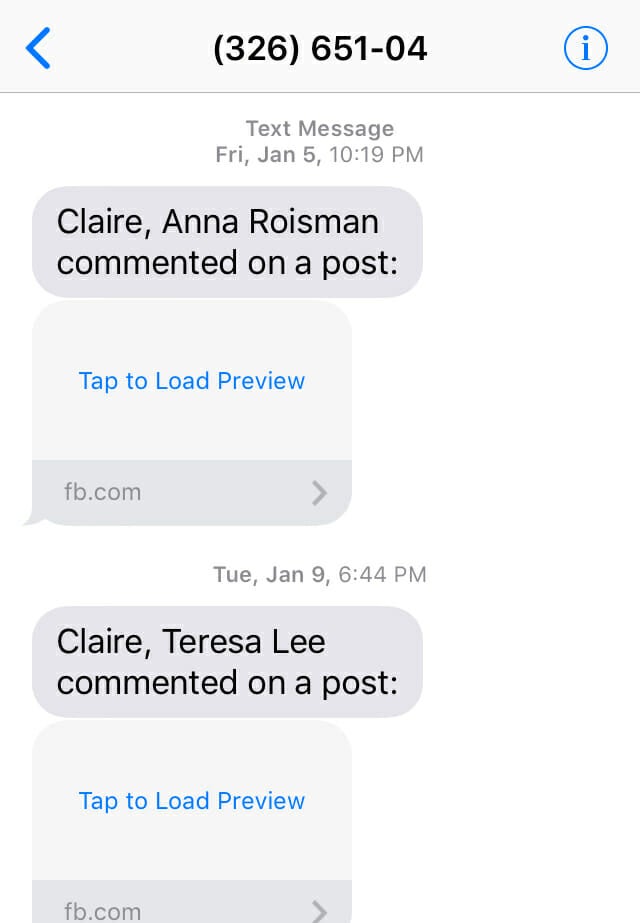

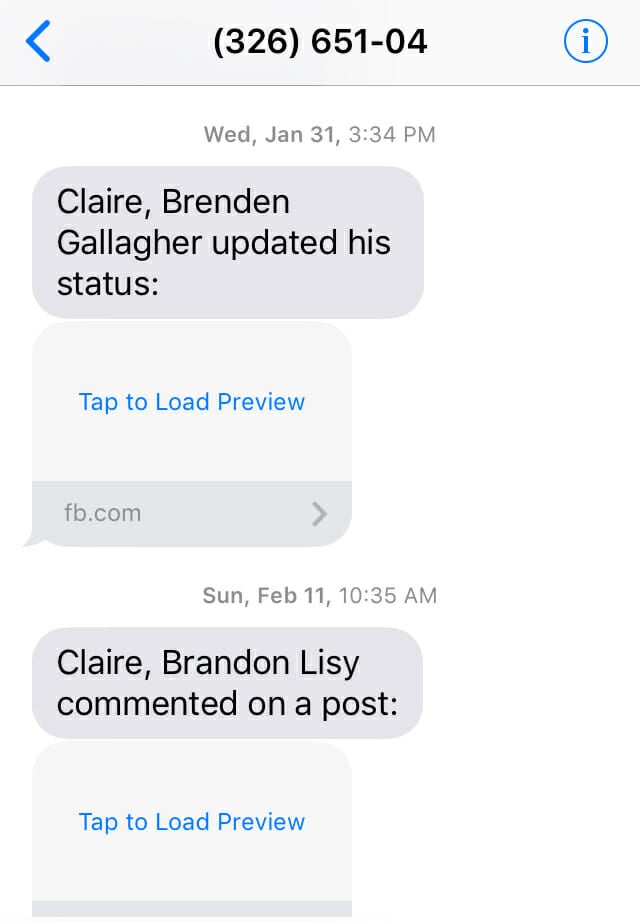

Not from my friends, wondering if I’d “unfriended” them. From Facebook. “Claire, [Friend] commented on a post.” Then, one day later, “Claire, [my live-in fiancé] updated his status.” I’d also hear about status updates from people I barely knew, events that other friends were going to, and photos that I wasn’t tagged in.

Every time, Facebook would address me by my first name, like a concerned mentor, often from different eight-digit numbers, sometimes multiple times per day. Even when I was out of the country, in a wildly different timezone, Facebook found a way to optimize those texts to send during daylight hours. Sometimes it seemed like Facebook was trying to stress me out: “Claire, your friends shared 2730 updates this week. Post your own.”

Usually, these texts would include a link. Once, I accidentally clicked on one, and it automatically reactivated my account.

This is my hell, and apparently, I’m not alone. In January, Facebook’s Q4 2017 report contained the admission that people spent less overall time on the social media site than in previous years. Privacy issues, failures to limit “fake news,” and general annoyingness has led many to release themselves from the grip Facebook once had on their lives. But just because you choose to leave Facebook, that doesn’t mean its interface will agree to let you go. Through a series of stalker-level communications, Facebook clutches onto former users with a thirst that cannot be quenched.

When I decided to deactivate, it wasn’t dramatic. I had spent nearly 12 years of my life on a site that, for the most part, bored me to tears. I couldn’t imagine spending another decade, much less another hour, passively scrolling through the News Feed. Deactivation is encouraged by Facebook’s customer service over full account cancellation. It allows you to keep your profile data and photos while still remaining hidden in searches and event invites. Besides, complete deletion is incredibly complicated to do and doesn’t guarantee that Facebook will actually remove your data from its site.

The thirst continued on Instagram, which is owned by Facebook, where I’d periodically receive a pop-up telling me that in order to use the app, I’d have to reactivate my Facebook account. This turned out to be untrue. Meanwhile, Twitter was still posting my tweets to my profile, because I’d failed to disable a Twitter extension before leaving Facebook.

Other users have complained of similar badgering in the form of emails from Facebook. One former user told Bloomberg that he started receiving security prompts from a Facebook customer service address. “It looks like you’re having trouble logging into Facebook,” the emails would say. “Just click the button below and we’ll log you in. If you weren’t trying to log in, let us know.” The user wasn’t trying. Another perturbed user noted that they were receiving push alerts on their laptop about friend requests.

Obviously, it benefits Facebook to keep users logged in. (How else is the company going to recoup the over $1 billion it is spending this year on narrative television programming?) But despite its urgings, deactivation is utter bullshit. You can still get friend requests, messages, updates to your account, and hear about the News Feed via text, push notifications, and email. Third-party apps can still use your Facebook data, unless you go through and disable them. As of right now, the only way to remove Facebook’s ability to text you without reactivation is to text “OFF” to the number 32665 (which I highly recommend).

Tech companies using annoyance tactics to re-engage customers is nothing new. People have been complaining that Spotify ramps up its awful ads after you cancel its Premium Service for years. Uber came under fire last year for continuing to track users, even after they had deleted the app. But when decades-long users of Facebook give up, the company doesn’t just make it difficult. It uses your personal connections, your friendships, security threats, and the fog of FOMO to manipulate you back in.

After announcing the Q4 report, founder Mark Zuckerberg said that Facebook will be rolling out new features to “make sure people’s time is well spent” and focus on “meaningful connections.” True, it seems like the last few years on Facebook have been all about fabricated milestones. From “friend anniversaries” to “top liked photos,” it feels like Facebook is struggling to give users an injection of saccharine positivity. None of this helps the fact that the site looks like a time machine to 2010 and often reads like a small town hall gone awry.

If you’re not ready to take the plunge and fully cancel your account, there’s only one way to make sure Facebook never contacts you again. Designate a legacy contact—a person who can control your profile after you die, and then have that person tell Facebook you’re dead. From there, Facebook can execute your “wishes” to permanently delete your account.

But unless you’re OK with confused acquaintances thinking you’ve died, we wouldn’t recommend it. It seems like we’re with Facebook till death do us part.