Nearly 25,000 union members were exposed last month in a massive data breach in Northern California.

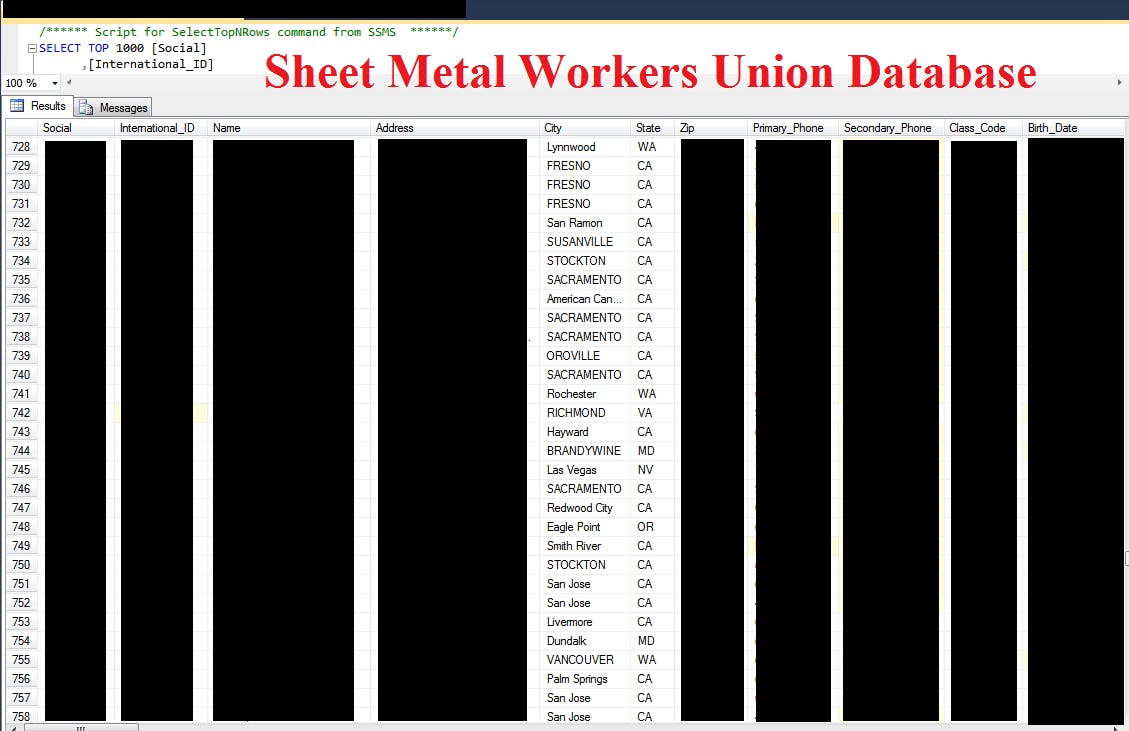

Members of Sheet Metal Workers Local Union No. 104 were left vulnerable to identity theft or worse by a misconfigured database, which was discovered online by Chris Vickery, an oft-cited cybersecurity expert and lead security researcher at MacKeeper.

The database, discoverable by search engine, was not protected by a password, and contained an extraordinary amount of personal information belonging to the union members: addresses, phone numbers, social security numbers, dates of birth, ethnicity, gender, marital status, family members and beneficiaries (plus their contact information), employment dates—up to 108 individual details per member—among other personal files detailing litigation and contracts, essentially any legal work performed by the union on behalf of its members.

Vickery, who earlier this year reported a data breach affecting 191 million U.S. voters, did what he always does when he finds protected personal information online: He contacted the owner to warn them. On Oct. 10, he left a voicemail with Local Union No. 104. “The database and other files were secured sometime shortly,” he said. He remains concerned, however, about the union members whose information was put at risk.

“I haven’t heard anything in response from the Sheet Metal Workers Local 104,” he said. “They have my name and phone number. They know that my message was accurate.”

It’s a scenario that seems to repeat itself, as Vickery routinely discovers leaky databases online, publicly accessible and unprotected. More often than not, the organizations whose records are improperly stored work to avoid disclosing security breaches, even to the employees, volunteers, and customers most likely to be impacted.

Last month, after he reported finding the personal information of roughly 5,000 Habitat for Humanity applicants and volunteers in Michigan, the organization and those responsible for maintaining its servers had little to say. A tech company, which likely hosted the data, pointed the finger at Vickery instead, suggesting the researcher who discovered the problem may have been responsible for causing it.

That also happens a lot, he says.

“Shouldn’t they have some questions for me?” Vickery wonders. The workers union files contained a slew of passwords as well; they were scrambled, but wouldn’t be impossible to crack. And there’s no way for Vickery to know whether or not others accessed the data. “Perhaps so that when they (hopefully) let their members know of the security failure, the union can at least be fully informed of every relevant detail,” Vickery said. “That seems like the reasonable thing to do.”

An attorney for the Local Union No. 104 said it was currently investigating the breach. Asked if they were planning to notify members their personal information was exposed, they declined to comment.

Update 5:46am CT, Nov. 17: Added comment from union attorney.