The federal government is evaluating its entire computer network to determine which systems are at greatest risk of a cyberattack.

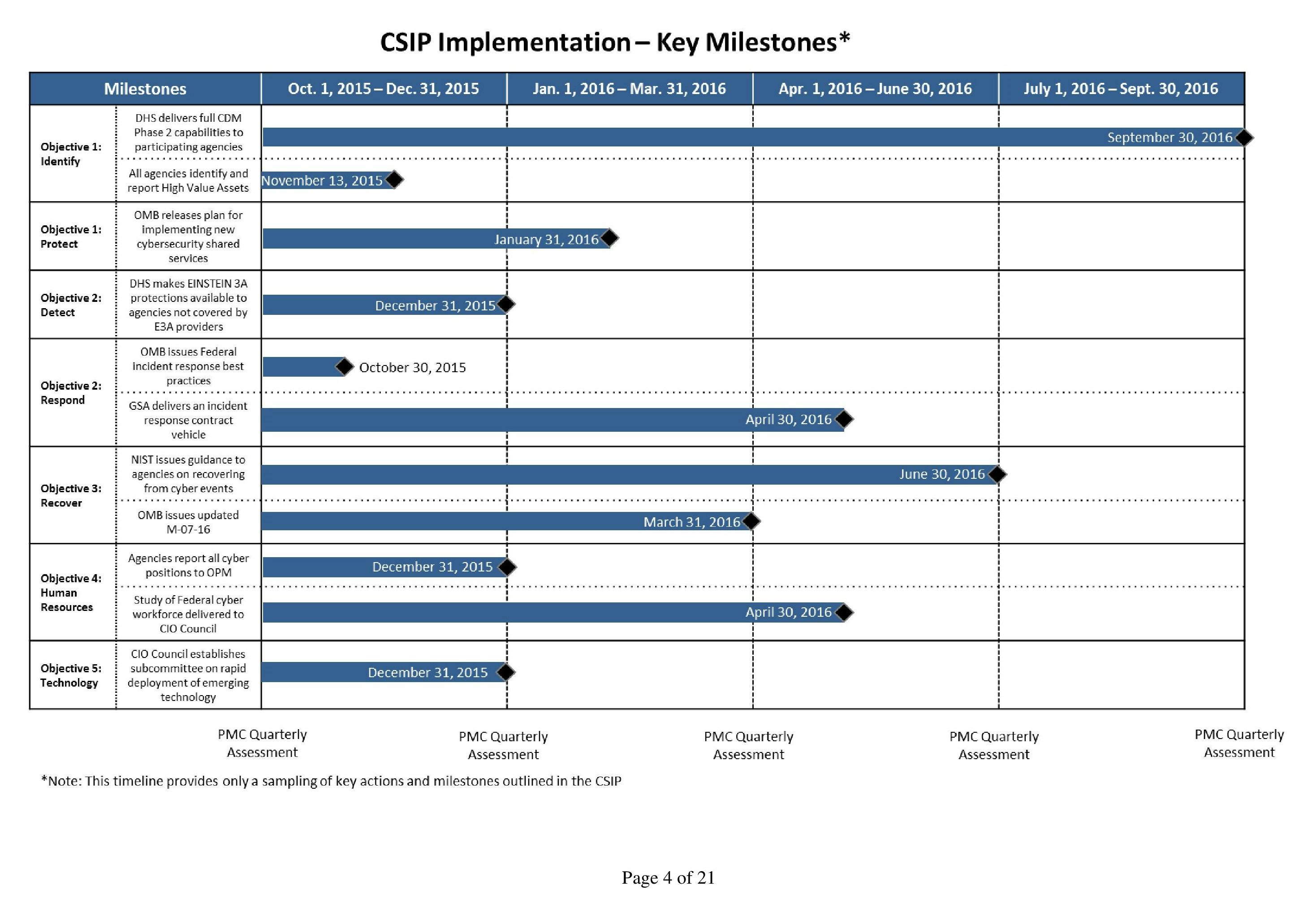

After a crisis-filled summer full of embarrassing news about a major breach of the Office of Personnel Management, in which hackers stole more than 22 million federal workers’ personnel records, President Barack Obama directed the Office of Management and Budget to conduct a month-long “cybersecurity sprint” in June. On Friday, OMB released the Cybersecurity Strategy Implementation Plan and provided an update on its continuing cyberdefense work.

The 21-page plan directs James Clapper, the Director of National Intelligence, to put together a team for a “threat assessment” of the government’s “high-value assets” and prepare a report on the most likely targets.

“The vast majority of Federal agencies cite a lack of cyber and IT talent as a major resource constraint that impacts their ability to protect information and assets.”

When that threat assessment is complete, agencies with systems that are at greatest risk must review their process for protecting Americans’ personal data in those systems. They will need to certify that that process both “accurately addresses risks” to personal data and details the steps taken to “mitigate those risks.”

The new plan also requires agencies to “patch all critical vulnerabilities immediately or, at a minimum, within 30 days of patch release.” Agencies must report any vulnerabilities that persist for more than 30 days.

In the strategy document, the government touted its success in promoting the use of strong encryption. It said that the overall use of strong encryption by federal workers had risen from 42 percent to 72 percent during the month-long cyber sprint alone. Among so-called “privileged users”—network administrators and other employees in senior positions—that number rose from 33 percent to just below 75 percent.

The Department of Homeland Security is charged with collecting and evaluating cyber threat indicators, samples of code and other evidence that offers clues to the origins, goals, and methods of cyberattacks. The new plan requires agencies to scan for intrusions into their systems within 24 hours of DHS transmitting threat indicators to them.

Congress is currently considering legislation to encourage businesses to share more of these threat indicators with the government, but the bills are controversial because of concerns over personal information winding up in the shared data.

In addition to the cybersecurity improvement plan, OMB also issued guidance to federal agencies about reporting security incidents in compliance with the Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA). The document for the first time issues guidelines for determining what constitutes a “major incident,” which agencies must report to Congress within seven days.

Major incidents, the guidance said, are situations where sensitive information has been “exfiltrated” and publicly shared; where agencies lose the ability to perform some or all critical services; where recovery from the incident is unpredictable or impossible; or where classified information has been compromised.

“Across the Federal Government, a broad surface area of legacy systems with thousands of different hardware and software configurations contains vulnerabilities and opportunities for exploitation,” White House Chief Information Officer Tony Scott wrote on the OMB blog. “Additionally, each Federal agency is responsible for managing its own IT systems, which, due to varying levels of cybersecurity expertise and capacity, generates inconsistencies in capability across government.”

The Obama administration wants to centralize much of that work, eliminating redundancies, inefficiencies, and communications gaps that have stymied federal cybersecurity responses over the last few years.

The federal cybersecurity plan places significant responsibility on the National Institute of Standards and Technology, a small agency within the Department of Commerce that creates technology standards like encryption protocols. Under the plan, NIST has until June 30, 2016, to create and distribute to agencies recommendations for recovering from “cyber events.”

The new plan also stressed the importance of Personal Identity Verification cards, which offer a second form of authentication on top of standard passwords, and it directed NIST to publish strategies for increasing the use of PIV cards based on the rollout during the cyber sprint.

Critics of the data-sharing legislation pending in Congress have argued that the government’s main problem isn’t access to relevant data, but access to trained cybersecurity professionals who can properly analyze it. OMB’s information-security guidance echoed this concern.

“The vast majority of Federal agencies cite a lack of cyber and IT talent as a major resource constraint that impacts their ability to protect information and assets,” the guidance said. “There are a number of existing Federal initiatives to address this challenge, but implementation and awareness of these programs is inconsistent.”

To address these issues, OMB, NIST, DHS, and other agencies are mapping the federal government’s “entire cyber workforce landscape” to spot “cyber talent gaps.” They will then issue recommendations for hiring or retraining personnel to fill those gaps.

The cybersecurity strategy focused mainly on securing access to networks, rather than the actual data on them. But it also suggested several ways to improve data security, including a digital rights management (DRM) scheme that encrypted data so it would be unreadable outside of a secure government environment.

“Cyber threats cannot be eliminated entirely,” Scott said in his blog post, “but they can be managed much more effectively.”

Photo via Elliott P./Flickr (CC by 2.0) | Remix by Max Fleishman