J. Pat Brown just wanted to know who thought the CryptoKids were a good idea.

After years editing the alt-weekly DigBoston, Brown started working at the government transparency organization MuckRock in 2014. MuckRock’s mission is helping people use the Freedom of Information Act to expose the government’s inner workings and assisting news organizations in turning that info into compelling journalism. While Brown spent much of his career in the news business, he was relatively new to using FOIA as a means of obtaining government documents and was looking for some opportunities to try the process out for himself.

That’s when he read a listicle from the satirical website Cracked entitled “5 Sites That Prove the U.S. Government Sucks at the Internet.” The story mockingly detailed a project by the NSA called CryptoKids—a website aimed at getting teens interested in cybersecurity careers using a cadre of hip, anthropomorphic animals who love to chill out, have fun, and decipher encrypted communications.

“I realized [that a FOIA request] could give some accountability to this,” Brown told the Daily Dot. “It’s not just that I can’t believe money was spent on this. I could actually ask questions about why this money was spent, who did it, and who was responsible for it.”

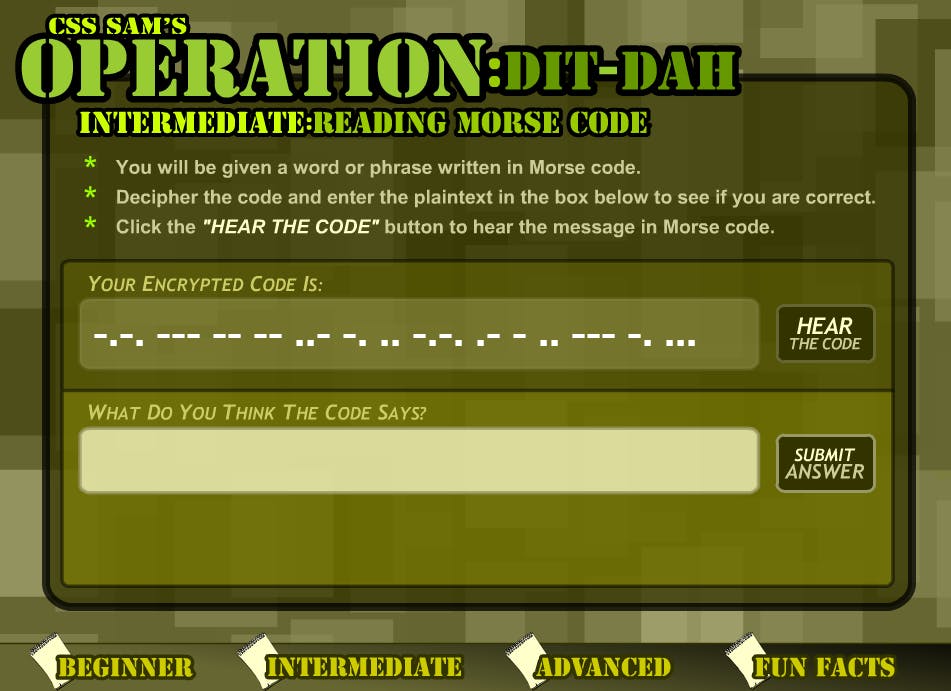

As he explained in a recent blog post, Brown filed a request to get more information about “who at the NSA signed off on making a saxophone-playing squirrel in safety goggles their kid-friendly mascot … [and] how can [CryptoKids character] Joules have a pet dog that acts like a dog when one of her friends is an anthropomorphized dog whose literal last name ‘Dog?’”

Two years later, he’s still waiting.

Even though this effort is an attempt to shed sunlight on one of the least serious aspects of what the National Security Agency does, Brown argues that these two years of almost complete silence are indicative of a culture of secrecy within much of the intelligence community that serves to undermine the sense of trust in government that FOIA was enacted to engender. The CryptoKids may be relatively trivial, but Brown’s experience carries implications about how the agency interacts with the public regarding all of its other activities.

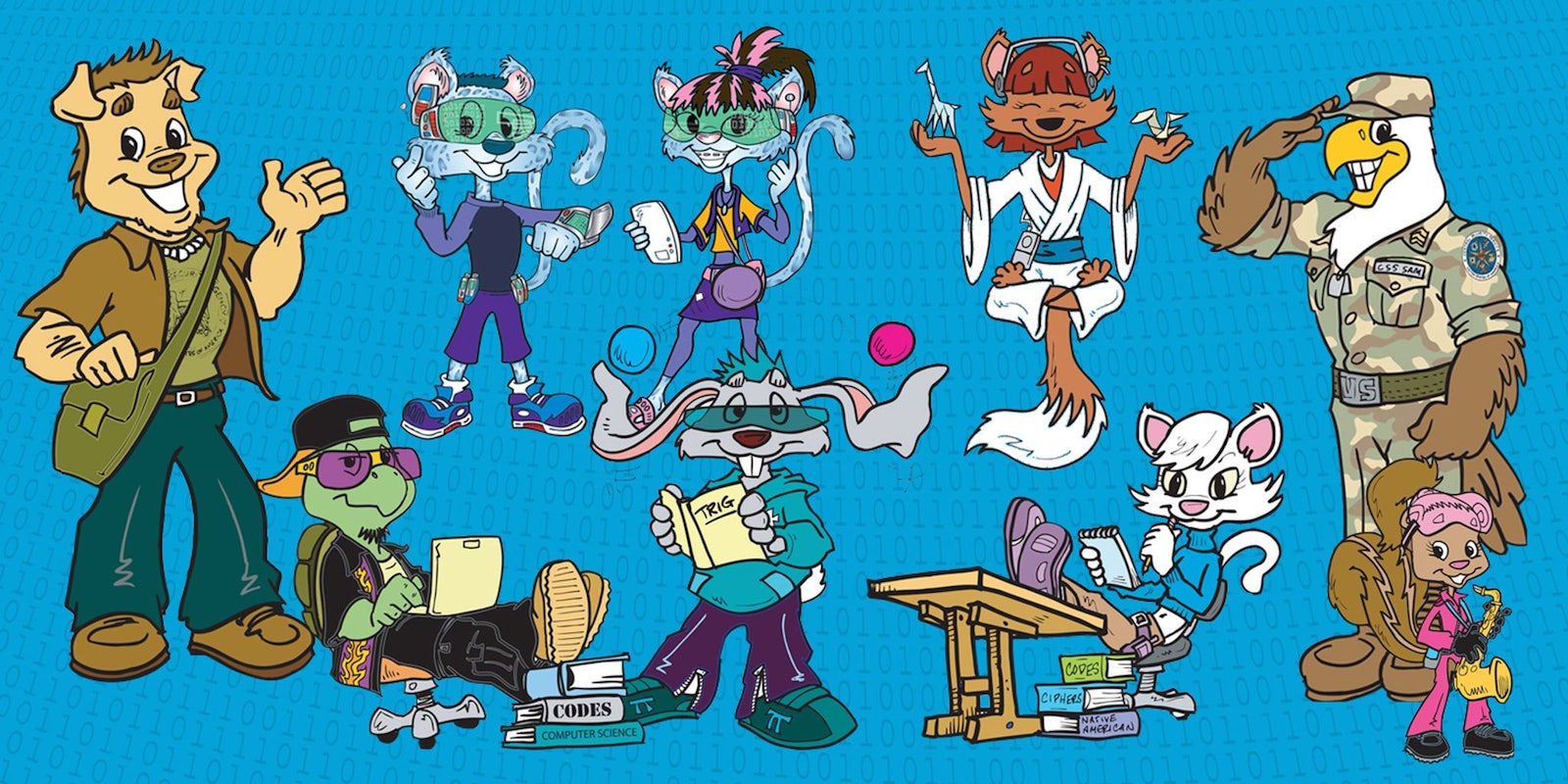

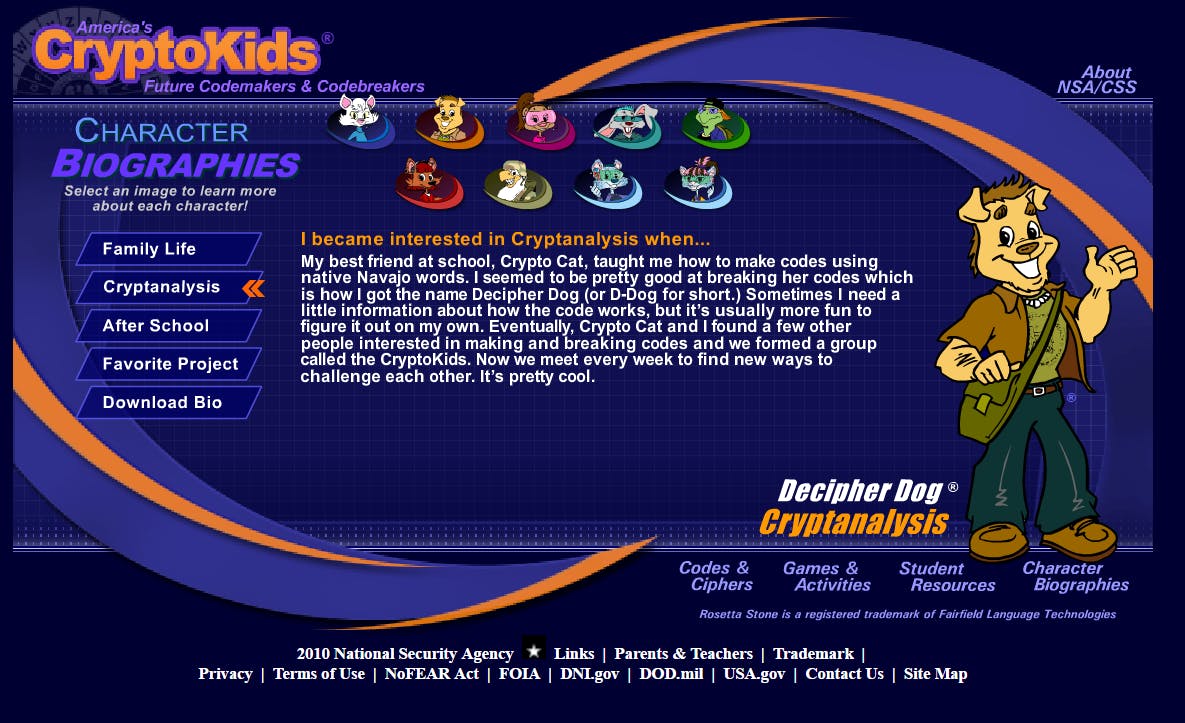

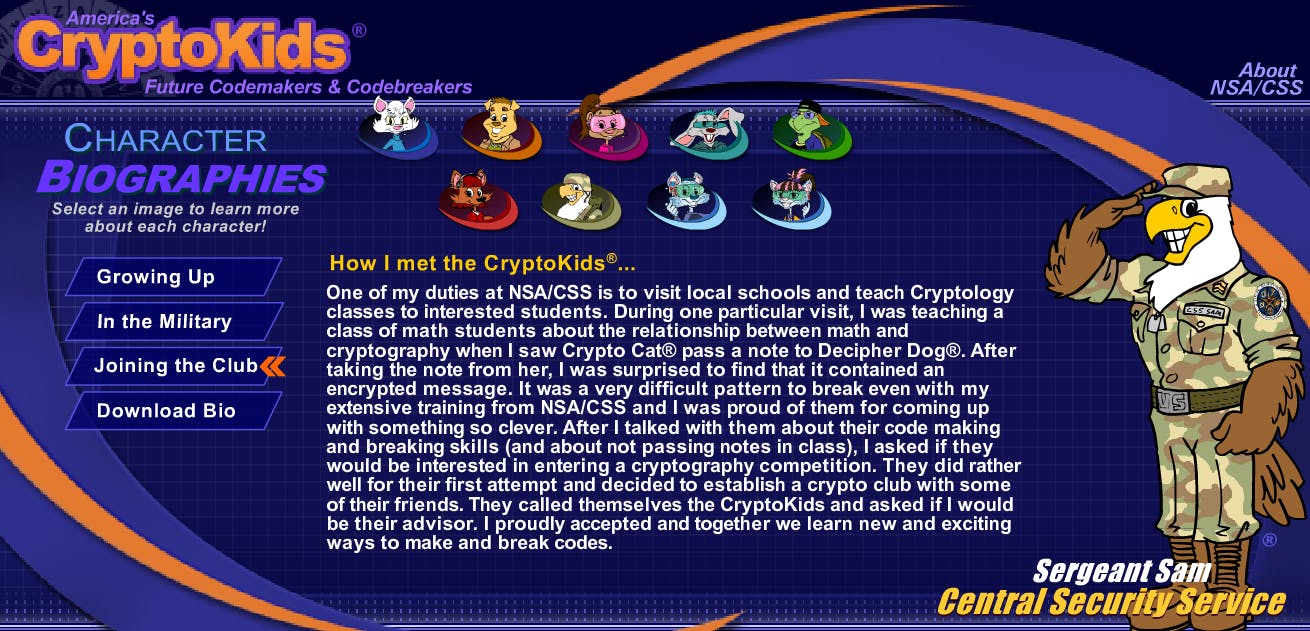

The CryptoKids website was launched in by the NSA in 2005. It features biographies of cool teen animals who are in a super-fun codemaking and codebreaking club.

The site has information about work-study programs at the agency for non-cartoon high school kids and summer internship programs for college students. It details the types of jobs available at the NSA—from signals analysts to mathematicians—and gives tips on what kids can do to gain the skills necessary to get those jobs. There are quizzes and games, like ones providing lessons in translating English into and out of Morse Code.

Also, there are pages of a coloring book to print out and fill in because why not?

While the entire thing seems, well, a little ridiculous, a lot of government agencies have similar programs aimed at giving young people an idea of what they do and possibly adding “federal official” to their list of dream jobs—hopefully between professional basketball player and astronaut. The National Counterterrorism Center’s Kids Zone, for example, features a squad made up of a child dressed like Uncle Sam and a laptop in a wheelchair.

In a era when government cybersecurity officials often feel understaffed and demoralized, getting STEM-inclined kids interested in public service early may be one of the only ways to combat brain drain away from government agencies and toward significantly higher paying tech jobs at places like Apple or Google .

Shortly after Brown filed his CryptoKids request, he got a response from the NSA. Based on the horror stories he had heard about the long delays the agency often forced on people who requested documents, the window between his submission and turning over documents was effectively the blink of an eye. What he got back wasn’t precisely what he was looking for. Instead, it was two pages of documents recounting how the American Library Association had added CryptoKids to its list of “Great Web Sites for Kids,” and Kids.gov featured CryptoKids on its homepage.

It wasn’t much, but Brown wrongly assumed it meant more would be soon forthcoming. He followed up a handful of times with the agency, but those two pages represent everything he was able to get on the Cryptokids.

“I didn’t realize that I had sort of fallen into a trap. When it comes to documents that are … per-processed and favorable, it’s usually very easy to get them … especially when dealing with the intelligence community,” he said. “But if you want anything else related to the actual impact of what people are doing, that’s when you start to see these tremendous delays.”

Brown, who has since filed countless FOIA requests with hundreds of different government agencies as part of his work at MuckRock, noted this experience is largely par for the course when it comes to dealing with agencies like the NSA—a quick acknowledgment that your request was received, which is required by law, followed by months, if not years, of silence. That’s because even assigning a request to a public-information officer can take up to 18 months, and processing the request, especially a complicated one, can take years.

“I am sympathetic when a FOIA officer says they are understaffed and there are only so many people that are working on this kind of stuff. I do understand that it is difficult for them to process that many requests,” he said, adding that the number of FOIA requests the NSA received after the Edward Snowden revelations led to a 1,000-percent increase in the number of FOIA requests to the agency. “But it’s a little bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy. … [Since] so few resources are put into FOIA, there is an arbitrary under-staffing of these FOIA offices because they want to divert your attention to the information that they’re releasing voluntarily rather than the information they’re releasing involuntarily.”

Brown noted that some agencies are considerably more difficult to pry information out of than others. He pointed to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) as being particularly helpful. It’s largely the agencies that deal with national security—the Department of Homeland Security, for example—that have cultures that view transparency as a distant second to gathering intelligence on suspected terrorists or patrolling the U.S.-Mexico border.

At the end of the day, Brown insists getting stonewalled on something as seemingly inconsequential as the CryptoKids shows that, when it comes to getting information out of the government that some official may not want public, persistence is key.

“If they quietly closed [my CryptoKids request] without telling me, I wouldn’t be surprised. But it’s not going to stop me from asking 10 more questions about it of other agencies. You can’t just ask one question, you have you be constantly asking at every different level. You can get answers, but it’s all about refusing to back down,” Brown said. “You run into all of this bureaucracy designed to make you unwilling to use … [public records laws]. That’s how the government manages to keep these things hidden in plain sight. Even though you’re entitled to this information, they just make it really frustrating. You have to always be asking and always be pushing forward.”

Representatives from the NSA did not respond to a request for comment.