On April 11, Oklahoma reported 74 new coronavirus cases and five deaths. In terms of the numbers, it was a pretty average day, if not lower than usual—the state’s curve even appeared to be flattening. Less than two weeks later, the governor would announce plans to begin lifting shutdown orders.

But for Megan Adkins, there was nothing normal about that day.

“I felt like it was very easy for people to dismiss: ‘Oh, there’s only two deaths, or one death today,’” she told the Daily Dot by phone in July. “I just felt like people weren’t looking at these numbers as if they’re real people with families and stories behind them.”

Families like hers.

“My dad passed away on April 11, and unfortunately, of course, we weren’t able to be there with him,” Adkins said. There was no family gathering; no funeral. And so: “It just kind of felt like he just disappeared.”

At first, she heard from a lot of friends, but over time, those messages started becoming scarce as friends started going back out, “like nothing’s going on.” Outside of her family, she didn’t know anyone else in Oklahoma who had a personal connection to the coronavirus; let alone anyone who had experienced a similar loss.

So, she turned to social media.

There’s been a well-documented surge in users on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter during the pandemic’s spread, with many publicly struggling to handle the accompanying increase in misinformation and conspiracy theories. Still, for some who have experienced or lost loved ones to the coronavirus, social media sites have provided an essential link to community in a time of isolation and confusion.

“I mean, I was about to delete Facebook,” Diana Berrent said, reflecting back to before she got sick. “It just seemed irrelevant. And then, it saved my life.”

In March, Berrent believed she had been exposed to the virus, but did not meet the qualifications necessary at that time to get tested. She vented her frustration at the situation on Facebook. To her surprise, the post was shared by thousands.

Because of that attention, a local politician helped Berrent to get tested, and she received her COVID-19 diagnosis. She started a Facebook group, Survivor Corps, to create a community of others like herself who had contracted the virus and were navigating the unknown “after” phase.

“[Facebook] is such a critical part of mine and so many other peoples’ lives in a new way, and one that we never could have anticipated,” Berrent explained of the group, which now has more than 85,000 members. “No one would ever want this, but given the circumstances, it’s been a godsend.”

As Survivor Corps grew, Berrent instituted strict rules to avoid the issues she saw in other coronavirus social media groups. No political posts or personal theories are allowed. No articles from Medium; no YouTube videos of doctors. You can share what worked for you, but you can’t suggest treatment for anyone else. She enlisted nearly 30 administrators to help her make sure these guidelines are followed.

“We call it the ‘epicenter of hope’ for a reason,” she said of the atmosphere she’s trying to cultivate. Members post about bright spots, like a sore throat finally easing after months, or being able to donate plasma after a testing negative. Meanwhile, “Long haulers” compare notes on new symptoms surfacing months after their initial diagnosis—hair loss, rashes, anxiety—which Dr. Natalie Lambert from the Indiana University School of Medicine compiled into an anecdotal study.

And then, there’s the increasing volume of members who have lost family or friends to the virus.

“We see these death notices all day long on Survivor Corps and they’re heartbreaking,” Berrent acknowledged.

People ask deeply personal questions that reveal both the regular, painful banalities that still exist—the burial planning, legalities, costs—and the uncertainty that surrounds the virus victim, even after death. One son, preparing to be a pallbearer at his father’s funeral, questioned whether attending the service would be too risky for his wife and children. Hundreds offer prayers, “hugs,” and heart emojis on posts about family members and friends who didn’t make it. Berrent said some members reached out to her about splintering off to create a grief-specific group, which she encouraged.

As the death toll from the coronavirus continues to climb, surpassing 150,000 in the United States and 600,000 worldwide, more of these communities are forming across social media platforms. “Grief: Releasing Pain, Remembering Love & Finding Meaning,” a private Facebook group that offers regular virtual meetings, has more than 16,000 members. Multiple others on the platform have rallied around a yellow heart as a symbol of remembrance. Within them, members share stories and discuss ways they plan to publicly memorialize those who died, whenever that is safely possible.

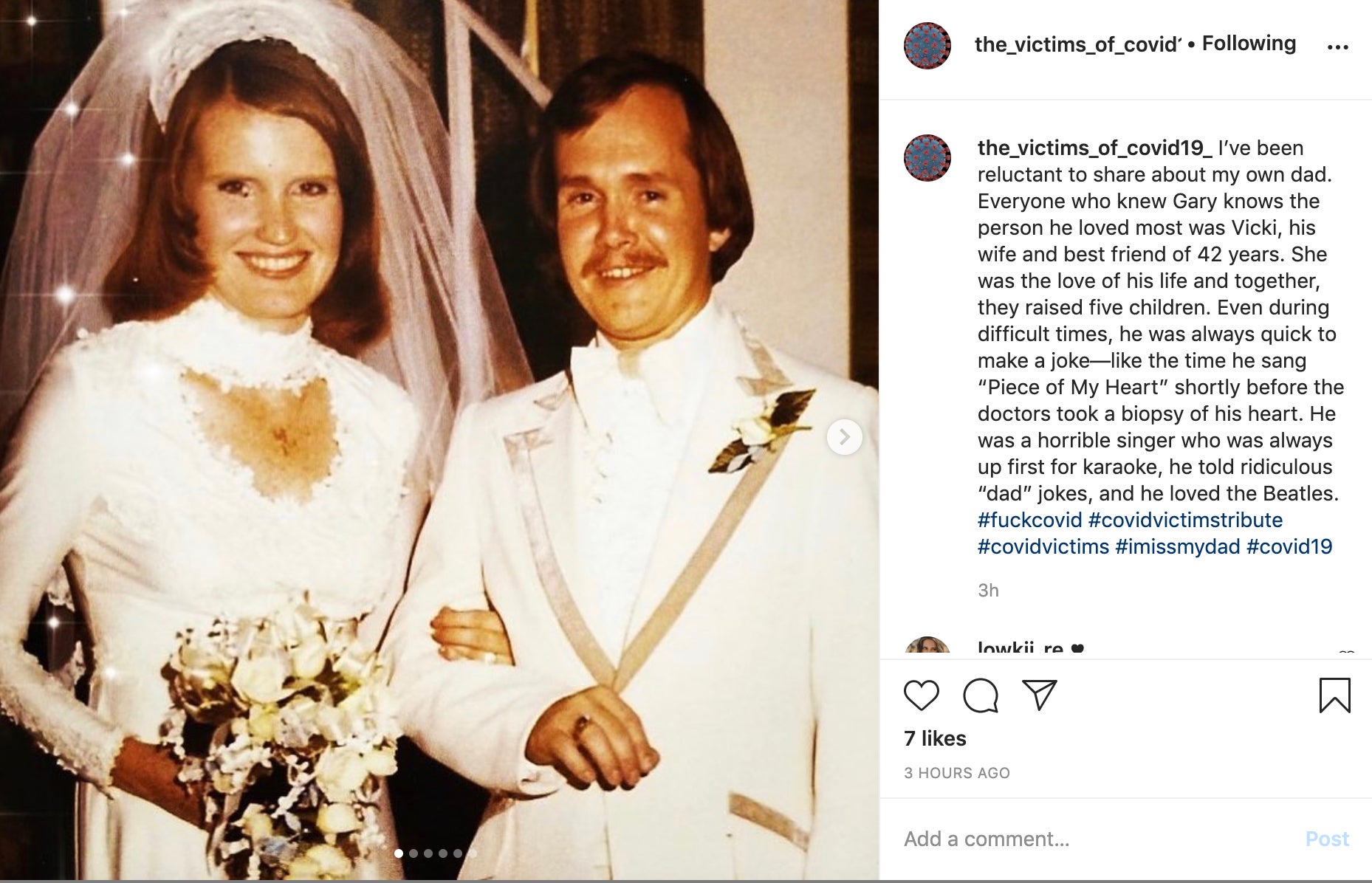

Adkins tried joining a number of these groups, but none felt quite right. Inspired by Humans of New York, she decided to create her own community, an Instagram account called “The Victims of COVID-19.” She invited others who have lost loved ones to send in photos and captions that she shares.

Among those who have reached out to her was a woman around her age whose father was hospitalized, and later passed away on the same day as Adkins’.

“It’s horrible that anyone else has experienced it, but it’s also been such an isolating experience,” she explained. “And so I found some comfort in knowing that there are other people who are having very similar feelings.”

In her first post in early July, Adkins admitted that she didn’t feel ready to talk about her father yet.

She wrote a draft, saved it, reconsidered it.

Then, two weeks after starting the account, she shared her story. Below a slideshow of photos of her father, Gary, through the years, she talked about his quick sense of humor, his “horrible” singing voice, and his decades-long marriage.

“It’s really hard to sum up who he was in just a short Instagram post,” Adkins said. But, at the same time, she sees the power in sharing on social media, a place where she can feel a little less alone, and put a face to the numbers.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled Diana Berrent’s name. The Daily Dot regrets the error.

READ MORE: