Over the past two years, BitTorrent has made monumental strides in proving that torrent technology can be useful for something other than watching Game of Thrones without an HBO subscription. By creating the BitTorrent Bundle marketplace, complete with paywalls, they’ve successfully shown that torrent files can be utilized as a profitable alternative to iTunes or Amazon, with releases from artists like Thom Yorke, RATKING, Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros, and David Cross, and deals with Drafthouse Films, Sony, and FilmBuff.

But it’s not just distribution BitTorrent’s seeking. Two years after its initial release, the company recently moved one of its programs, Sync, out of the beta stage. The “Pro” version costs $39.99 a year, and with Sync 2.0, they’re taking dead aim at the likes of Google Drive and Dropbox with a non-cloud-based approach to file sharing.

As somebody who occasionally does remote video editing, which involves sending and receiving large files, I decided to give Sync a test drive. I downloaded the program onto my Mac and discovered it works a lot like Dropbox: You designate a folder to share and put whatever files/other folders you want to share inside of that folder.

Unlike Dropbox or Google Drive, you can’t simply share the files with a URL download link; anybody wanting to access the files must do so through Sync. It’s incredibly simple to install, but if you’re trying to send a file to somebody with zero computer skills—who finds clicking on a direct download link to be very difficult—you’re better off mailing it to them on an external hard drive.

Sync’s biggest asset isn’t actually its ability to send people files—it’s the fact that, by linking devices together on one account, it basically creates a long-range local access network. Any file or folder edited on one device is updated to all other linked devices, although an archive feature can retrieve anything that was overwritten by something worse than the original.

Once I had my folders set up properly, I downloaded the Sync app to my Galaxy S5 and set about linking it to my computer. This involves toggling the “link device” function on your desktop, which brings up a QR code. Selecting the same function on your phone toggles its camera, which you then have to align with the QR code on your computer screen to successfully link the devices. The whole process feels like something out of a Mission Impossible film, and it makes you feel confident that somebody won’t be able to hack into the nude selfies you’ve stashed away in your Sync folder.

After three days of my phone giving me an error message after scanning the QR code on my desktop, telling me that it couldn’t link my devices, I uninstalled the program from both my phone and computer and reversed my tactics: I installed it on my phone first, making it the original account, then linked my computer to it (which is the same QR code-scanning process). This time, my phone notified me that you can’t link to another device that’s set more than 10 minutes off. My mind reeled—was my computer existing in the future? Could I use this wormhole to exploit the stock market and the world of sports betting?

After realizing my computer’s clock was 30 minutes off, I set it to the correct time and the two devices were linked within seconds. This probably isn’t an issue anybody but me would run into, but check your clocks.

At any rate, it was time to sync a file. For the first test, I started small, with a whopping 45MB version of this photo that I made custom for this experiment.

I dropped the file into the shared folder on my computer, and with the “sync all” option toggled on both my computer and phone, the file automatically began downloading onto my S5 (if this option isn’t toggled, ghost files will appear on linked devices that can be manually selected to download). With both devices connected to the same Wi-Fi network, the download speed hovered between 3 and 4 MB per second, which made for an impressively quick transfer.

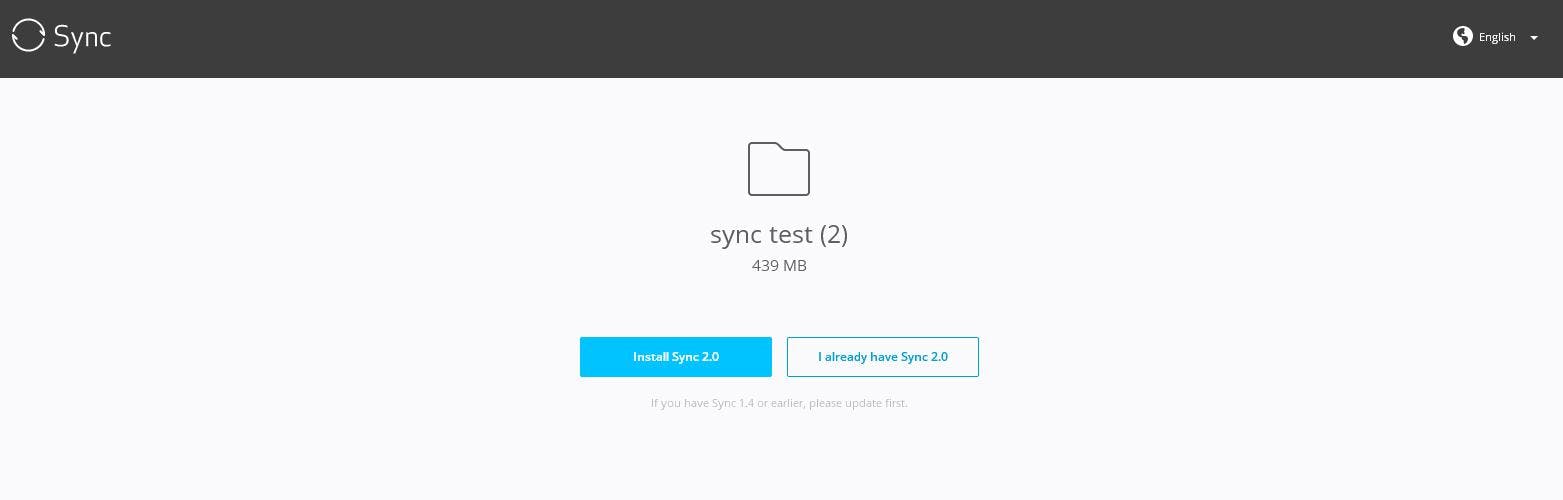

Google Drive and Dropbox also hit similar speeds, but being cloud-based systems, they require you first upload a file to the cloud before it can be accessed remotely. This isn’t a big deal when you’re dealing with a 45MB file, but when you’re dealing with files in the gigabyte range, cutting out the upload step is a massive time saver. Since you’re dealing with direct connections with Sync, you simply drop a file in the shared folder and it’s immediately available to download to a linked device. Or you can share the folder with an unlinked Sync user by sending them a lengthy URL, which will take them to a page that looks like this, prompting them to either open or download Sync:

When sharing a file with a user on a device not linked to your account, you can set an expiration date for the URL link and also designate whether the receiver has editing permissions. If you’re sharing to somebody’s phone—and they’re sitting next to you—you can also share a folder via a QR code that they can scan.

Unfortunately, there is a downside to cutting out the cloud middle man: Since you’re dealing with direct peer-to-peer connections, you can’t access files from a device that’s turned off or doesn’t have Sync currently running. If you’re using it primarily to shares files between your office computer and home computer/phone and like to power down your computer when you leave the office, you’re going to have to change your habits and start leaving it on (and set it to not go to sleep).

This isn’t a problem if Sync is being used to share files between an entire office, though, and the program seems to really shine when it’s linking several devices together. Due to the fact that it’s basically a GUI mask paired with a security system for creating and sharing torrent files, it’s a “the more, the merrier” situation—the more peers you’re connected to, the faster things go.

If your devices aren’t currently connected to the same Wi-Fi network, having more peers is a bit important—when I cleared the test image from my phone and re-synced it at a friend’s house (with a perfectly adequate Internet connection), the download speeds hovered around a somewhat unimpressive 400-600 KB per second, whereas Google Drive maintained its 1-2 MB per second speeds.

Still, with large files, it beats having to upload them to a cloud, which usually results in at least an hour passing for you to remember that you need to download them. To test Sync’s ability to handle large files, I dropped a (legally) downloaded copy of the modern classic Trailer Park Boys: Don’t Legalize It into my share folder, then synced it to my phone at a Starbucks. The 6.5 GB file took about three hours to download, and that’s not too shabby for only being connected to one peer.

All in all, Sync 2.0 is a pretty nice thing to have around. For stuff like remote film shoots that need quick turnaround from editing bays on the other side of the country, or band members living in separate states recording an album in the style of the Postal Service, the program is a godsend.

Many users are upset about Sync’s move from the beta stage, as the Pro version of Sync 2.0 has essentially taken features that were previously free and added an annual fee of $40. But with Microsoft OneDrive and Google Drive’s cheapest offerings (after the free 15 GB storage options) being about $25 a year for 100 GB of space, and Dropbox costing $100 a year for storage space above 2 GB (and having a max limit of 1 TB), Sync’s $40 a year for unlimited space doesn’t seem like such a bad deal.

If you’re not using the Pro version (your download gives you a 30-day trial) and stick to the free one, you’ll lose the ability to link your devices, but you can still send files to unlinked accounts. If you’re only using the program for the occasional large file transfer and not as a continually synced network of folders, the free version will do you just fine.

Another nice touch: The phone app comes with a “camera backup” option, and switching it on resulted in my 1.6 GB of photos traveling from my phone at Starbucks to my computer at home in about 45 minutes.

Despite the fact that Sync doesn’t use cloud-based technology and the photos backed up from my phone should be safe from hackers, I’m still going to treat my nude selfies the same way I always have: photographing them exclusively with Polaroid instant film and immediately burying them in my backyard.

Photo by Joey Keeton