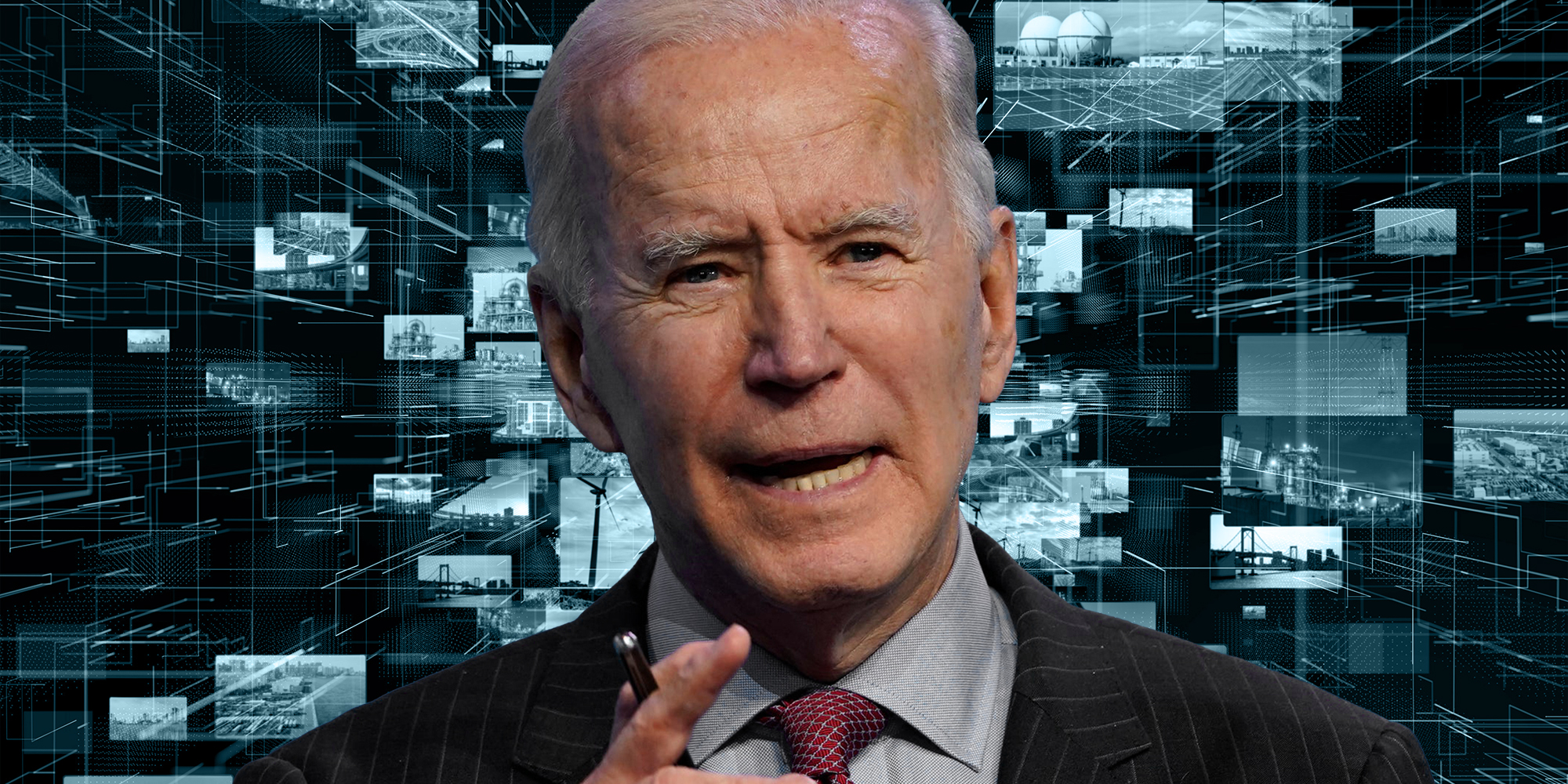

When President Joe Biden unveiled the American Jobs Plan, one of the standout elements was his proposal to invest $100 billion into expanding broadband access across the country—or at least it was. The Biden administration decided last month to lower its proposed investment down to $65 billion.

While the Biden administration made decision with the hopes of “seeking common ground” to match the Republican offer for getting the bill passed, the decrease seemed contrary to the intentions of the president.

According to the Washington Post, talks on the infrastructure package broke down last night. While the White House is still working to pass it, given the recalcitrance of Republicans on the pricey proposal, it's practically guaranteed that in whatever deal is struck, the money for broadband won't be going up.

The president has consistently argued that “broadband is infrastructure” as he's pushed the American Jobs Plan, which is a massive infrastructure proposal.

Much of the broadband push has been inspired by the deleterious effects of communities being isolated at home during the coronavirus pandemic. Not only did it make access to telehealth services in low-speed internet areas difficult, it severely inhibited the ability of poorer students and employees to complete their assignments in a timely and functional manner.

Essentially, the country's long-existing digital divide—the gap between people who have access to high-speed affordable broadband and those who don't—was highlighted by the pandemic.

While the exact details of Biden’s broadband expansion plan remain vague, the package is the most significant investment made into broadband expansion by a presidential administration, even after the Biden administration lowered the investment and billed it as a compromise. But how much would it cost to fix this problem?

“Our expectation is about $150 billion,” Johnny Park, CEO of Wabash Heartland Innovation Network, reportedly said at a recent congressional hearing. Biden's plan is now less than half that.

A different study from Tuft University predicted that $240 billion would be required to fill in the gap.

But regardless of the estimated cost, there's a sense that current estimates provided by the administration are not enough to fill the gap.

“It’s best to not get hung up on a magic number that will solve the digital divide,” Dana Floberg, a policy manager at Free Press, said. "Suffice to say that we know it's an expensive problem, and $100 billion certainly sounds better than $65 billion.”

Floberg argues that the broadband investment could significantly fill in the rural gaps, but it would not necessarily ensure that the regions would have optimal speeds.

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulations require that any broadband connection installed needs to be able to handle 25 Mbps a second for downloads and 3 Mbps upload. That definition has been in place since 2015, and there's been a push by lawmakers and tech advocates to update the minimum speed requirements to 100/100 Mbps.

Another issue that the FCC faces is how it tracks who has broadband access, which makes the exact amount of funding needed to help close the digital divide difficult to estimate.

Current FCC reports estimate that 14 million Americans lack broadband access. However, this data relies on Form 477, which only requires one household inside a Census block to have broadband to count for every member of the block. This practice has led many to believe that the FCC's numbers are unreliable.

Tyler Cooper, the editor-in-chief at Broadband Now, estimates that the numbers are much higher than what the FCC has reported.

Broadband Now manually checked more than 58,000 addresses to see whether wired or fixed wireless service was available in particular areas. Through this method, Broadband Now found that 42 million Americans likely lack meaningful broadband access.

Issues like unreliable counts are what concern some experts when it comes to expanding broadband. While large bills like the American Jobs Plan sound positive, some experts believe they require meaningful regulation and proper definitions for its spending.

“$65 billion invested well is much better than $100 billion invested badly,” says Kristian Stout, director of innovation policy at the International Center for Law and Economics.

Stout has expressed skepticism about using government funding to help expand broadband in unnecessary areas. Stout argues that municipal broadband may diminish competition and make it harder for smaller companies to compete or significantly impact a local level. It would also not answer the specific struggles related to pricing.

Cooper is less convinced, arguing that municipal broadband would help expand the capabilities of businesses in less-wired areas. Biden's current infrastructure plan prioritizes prioritize building in underserved and unserved areas and would support local-owned, non-profit, and cooperative broadband networks like municipal broadband.

Where will Biden's $65 billion for broadband go?

While Biden might eventually get the infrastructure plan passed—with or without Republican support—the specifics on how the funding will be used would still need to be debated in Congress.

“I think that the prioritization of the funding is going to come into the limelight at the legislative level.” Cooper told the Daily Dot. “You have Democrats who propose prioritizing a municipal deployment for these funds, and figuring out how to dole out that funding. The Republicans take a different view and are generally opposed to municipal broadband.”

The states have mixed policies on the matter. Currently, 18 states restrict access to municipal broadband. House Republicans also proposed a national ban on municipal broadband in February 2021, arguing that the ban would “promote competition” and “encourage private investment.” While the bill failed to pass in Congress, it reflects the Republicans’ anticipated resistance to the American Jobs Plan.

Cooper, Floberg, and Stout all echoed a similar sentiment: It is difficult to know what the decline in spending will affect in regards to congressional spending because of the overall the vagueness written within the American Jobs Plan regarding broadband.

However, Floberg pointed to the Accessible, Affordable Internet for All Act (AAIA), co-sponsored by Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-S.C.) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), which is part of the House Democrats infrastructure package.

The bill currently contains significant funding for deploying broadband to areas with no service at all, as well as to underserved areas. The bill also includes increased funding for the Emergency Broadband Benefit, a temporary coronavirus-related program that offers badly-needed financial assistance to low-income families struggling to afford an internet connection.

The investment into broadband's success will depend on the level of compromise the Biden administration can acquire within the Senate, where the filibuster continues to exist as a significant barrier to the passing of such a bill.

But suppose it can pass in the immediate future: in that case—even though it's $35 billion less than originally proposed—it would become a substantial stimulus toward fixing the state of American broadband.