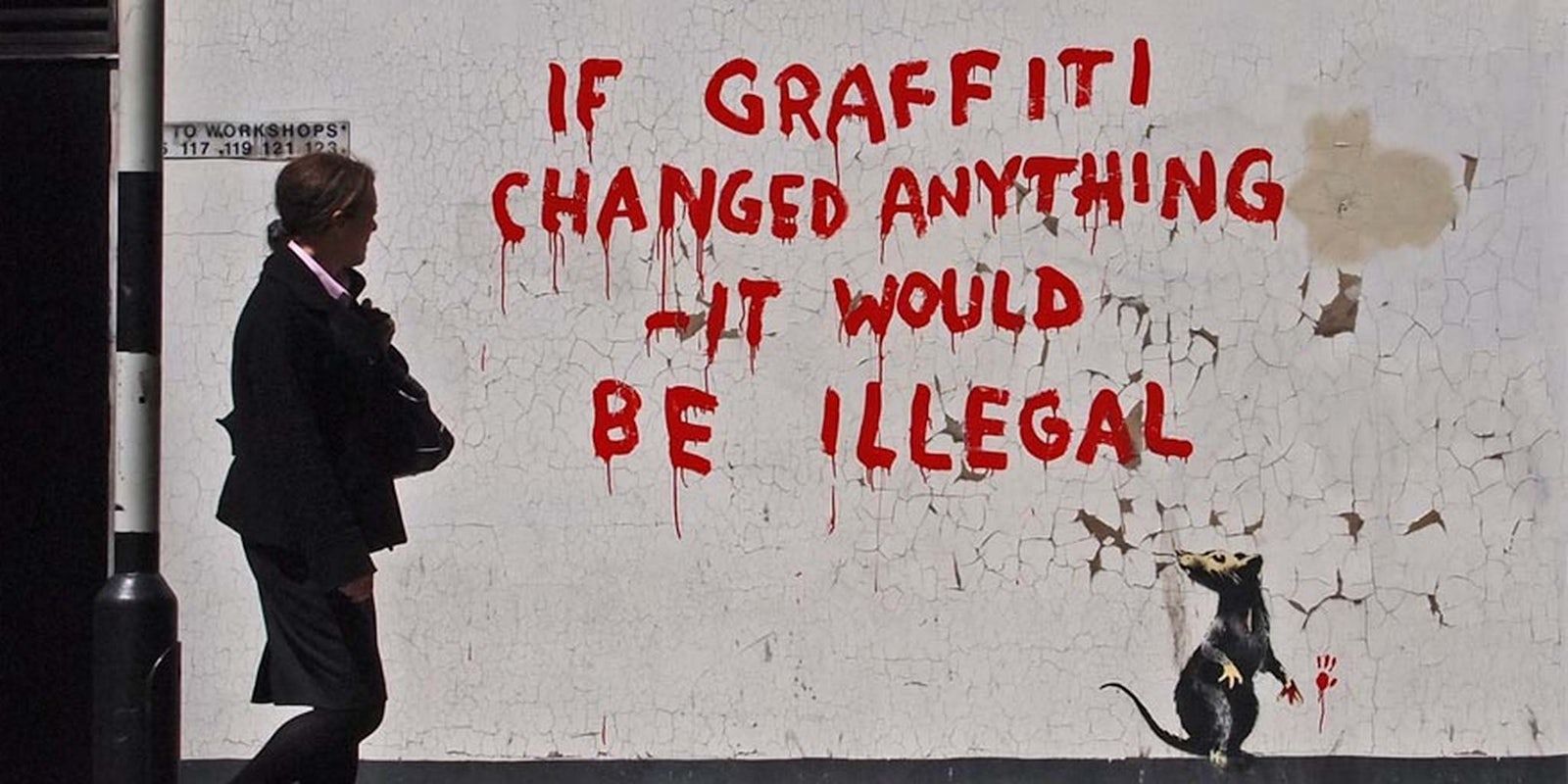

Scientists may have just unmasked the world’s most elusive artist.

In a study published last week, researchers seemingly confirmed a long-held theory about the street artist Banksy‘s real identity by cross-referencing the locations of Banksy pieces with the main suspect’s known addresses. Geographical profiling is typically used in criminology, but a team at Queen Mary University of London wanted to see whether it would work to identify the anonymous, guerrilla graffiti artist, too.

The authors of the study stopped short of saying that they’d positively ID’d Banksy after lawyers for the artist got involved, but QMUL biologist Dr. Steve Le Comber says he’d be “surprised if it’s not him.” The man they named, Robin Gunningham, has been a prime Banksy suspect since the Mail on Sunday discovered him in a 2008 investigation.

Sometimes publicly available data, collected and analyzed, reveals things that weren’t obvious before. Instagram recently banned an app called Being that let users see the site through others’ eyes by looking at a photostream from everyone the target follows. The list of people you follow on Instagram is public, but the company didn’t expect anyone to use it in that way.

The locations of Banksy’s works and the past addresses of Robin Gunningham are similarly public, but when you combine them and analyze the data, you get something that was not previously out in the open: Banksy’s (probable) real name.

That’s already raising red flags for some. Shouldn’t we be wary of applying the same techniques we use to stop serious crime in the hunt for a counterculture artist?

If it doesn’t concern you that big data is being used to target subversive artists, you need to study more history. https://t.co/949uzdRKs4

— Dino A. Dai Zovi (@dinodaizovi) March 6, 2016

@dinodaizovi @HughRundle bit of a worry when #streetart artists #banksy being targeted by academics / scientists using public research funds

— Paul Jewell (@pdjewell) March 7, 2016

The authors of the study suggest that the same application of big data to patterns of graffiti could be used to suss out hidden terrorist cells before they strike.

“More broadly, these results support previous suggestions that analysis of minor terrorism-related acts (e.g. graffiti) could be used to help locate terrorist bases before more serious incidents occur,” the researchers write, “and provides a fascinating example of the application of the model to a complex, real-world problem.”

At its best, big data—and even this specific technique—can certainly change the world for the better. The BBC points out that geographical profiling has been used for everything “from tracing infectious disease outbreaks to locating the roosts of wild bats.”

But at its worst, predictive analytics can violate our privacy—or even kill us.

The U.S. government already relies on big data to target drone strikes in Pakistan, and Ars Technica reported last month that the practice may have killed thousands of innocent people. A security researcher told Ars that the algorithm is “completely bullshit” because “there are very few ‘known terrorists’ to use to train and test the model.”

The National Security Agency’s SKYNET system, revealed in documents leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, allegedly works by tracking cellphone metadata to determine people’s locations, daily routines, and shared contacts. But information on a group of just seven terrorists was reportedly used to sift through cellular records collected from 55 million people, potentially resulting in innocent people falsely identified as extremists.

This is a problem without a clear solution, though. Big data isn’t going away, nor is it clear that we should want it to. All we can do at this point is to be as informed and judicious as possible about the personal information we make public online, and support limits on how much of our private data governments and law enforcement can collect and what they can do with it. Maintaining a right to encrypt our data would be a start.

If even Banksy can’t keep a secret, though, that doesn’t bode well for the rest of us.

Photo: Francisco Uhlfelder/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)