Opinion

In the fight against fake news, it’s not up to internet giants like Facebook to ensure what you’re reading is trustworthy and accurate. It’s up to you.

Whether you’re searching Google or browsing your social media feeds, you cannot simply take a headline at face value. Websites are clamoring to make money off of your eyeballs, trying to game the system for clicks and pageviews—and some sites are willing to do this by any means possible, with no regard for social consequences. This is something the American public is having a difficult time understanding, and something tech companies are desperately trying to remedy.

Facebook, largely blamed for the “fake news” issue popularized after the 2016 election cycle, has implemented a number of tools and algorithms to stop misleading articles from cropping up in your feed. It’s made it easier for users to flag fake news themselves, and it began using third-party fact checkers to verify flagged stories. Most recently, Facebook has also tackled ways to keep misleading news sites from making money on the platform and offered tips for how to spot fake news.

“False news is harmful to our community, it makes the world less informed, and it erodes trust,” Facebook’s VP of News Feed Adam Mosseri wrote in a recent blog post.

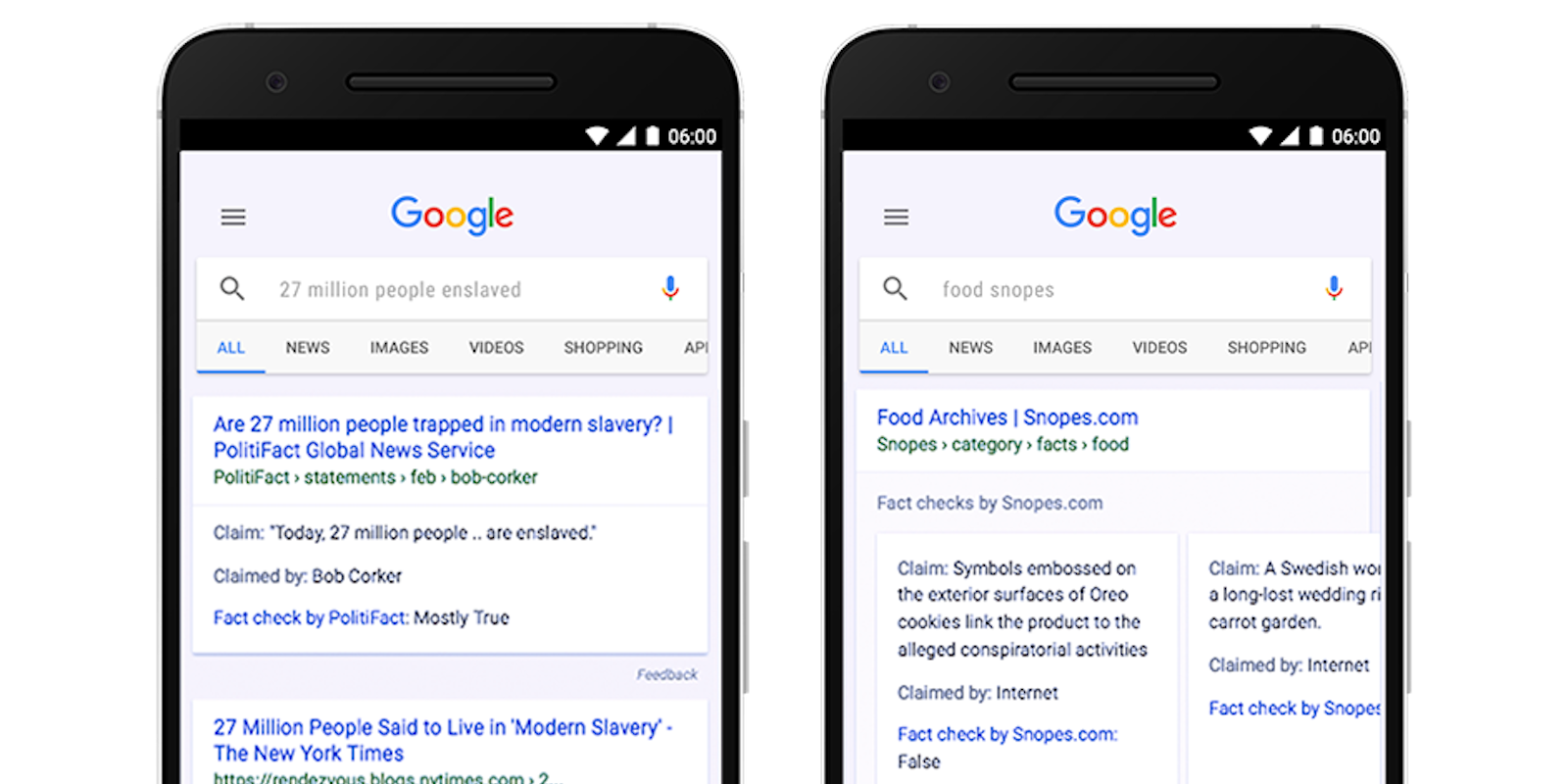

Google is also battling this issue. The search giant has similarly begun using third-party fact checkers for articles that crop up in Google News and Search results. Soon, when you Google a popular stat, you will quickly learn whether it’s real or false. Hopefully, this will help stop folks from perpetuating out-of-date or completely made-up “facts.”

The real problem

What Google and Facebook are doing is merely a Band-Aid for a bigger problem, though. We aren’t using our critical thinking skills as we browse the Internet. We see a headline that enrages us and click “Share” without a second thought. We read an article that confirms our long-held beliefs and treat it as fact, without examining the source of that information.

The problem extends beyond just news articles, too. A friend, looking for a new iPad case recently, couldn’t remember what model iPad she owned. She Googled her tablet’s model number, saw it was an original iPad, and shared the case she was planning to buy. Something didn’t feel quite right, so I asked her to relay the model number information to me, and I searched as well. My search revealed that she did not have a first-generation iPad, but rather a fourth-gen model.

You see, the top search results for that query were from a seller who’d SEO’d the shit out of its products. “First generation iPad” featured prominently in the SEO title, so she assumed that’s what she owned. Below that result was a link to Apple’s website detailing the model numbers for its iPad line—where I learned the truth.

In today’s digital world, you cannot search for something and trust the first result that crops up. Luckily, there’s a very quick way to fix this problem.

What we need to do

To avoid fake news and internet scams, there needs to be a fundamental change in the way we think about getting information online. We need to teach our fathers, grandmothers, children, and friends to use critical thinking skills before trusting what they read. At the very least, we really need to beat into people’s heads that the results that show up at the top of Google are often advertisements—and often misleading.

Beyond that, there are a few quick, easy questions you can ask yourself before trusting anything you see on social media or in search.

1) Who’s the source of the information?

If it’s one of these 25 legitimate-sounding websites, it’s likely false. Move along. If it’s a website you’ve never heard of, try to find if similar information is also printed—not just by other sites—but by reputable places like the New York Times or scientific journals. If you can’t find additional support, don’t trust it.

2) Does it sound too good to be true?

Ah, the hallmark of the hoax. When it sounds too good to be true, it probably (almost definitely) is.

3) How old is it?

The internet is constantly circulating and re-circulating stories. Check the date something was published; you may be surprised to learn it’s actually several years old and being taken (in today’s world) completely out of context. If a story is published without a date, that’s also a sign you should question its veracity.

If you want to be seriously thorough, FactCheck.org has a handful of other ways to check if a story is real or not. However, I find with the three questions above, I can quickly and accurately ascertain whether something sounds legitimate within a matter of seconds. (Then, of course, you’ve got to take the next step: reading the content and judging whether it lives up to your first impression.)

You can point fingers at Internet giants. You can say they need to improve their algorithms so we can lazily search without engaging a brain cell. But with the vast amount of information produced each day (2.5 exabytes’ worth, according to Northwestern University), it’s becoming an increasingly complicated algorithmic mountain to climb. On top of that, let’s be real: You shouldn’t be trusting a company that makes money off of your browsing to tell you what is and isn’t fact. That’s kind of like trusting pharmaceutical companies to tell you what illnesses you do and don’t need to treat.

Unless the structure of the Internet fundamentally changes, discerning what’s “real” and what’s “fake,” what’s “legitimate” and what’s a “scam,” will continue to fall on users. And those of us who are enlightened about how this game really works need to help educate those who are stuck in the Ask Jeeves era.