The only man to lead both the National Security Agency and the Central Intelligence Agency warned the Obama administration on Monday to drop its demand that Apple help the FBI unlock a dead terrorist’s iPhone.

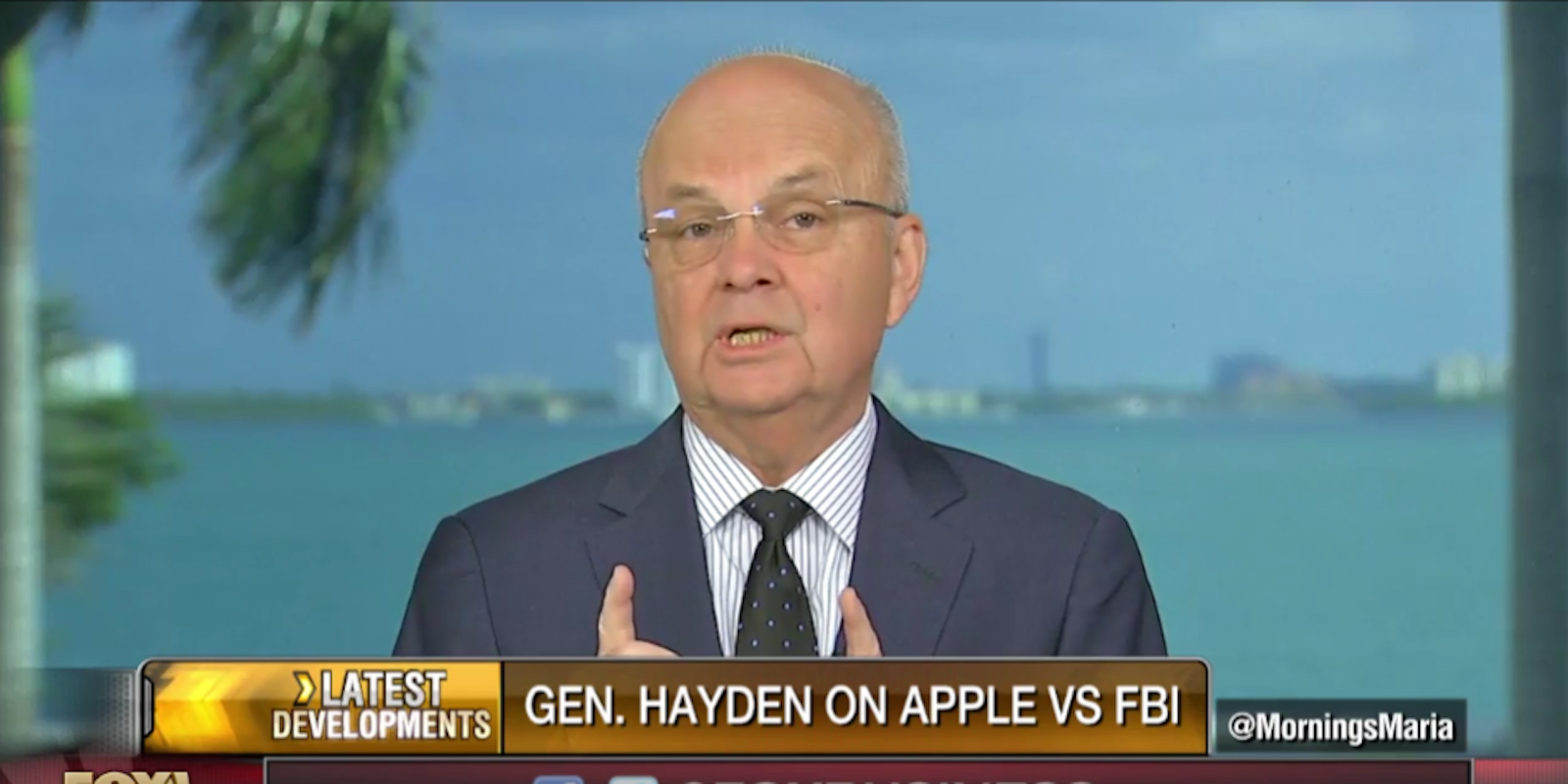

“I think it’s a close but clear call that Apple is right on just raw security grounds,” Michael Hayden, now a principal at the Chertoff Group, told Fox Business Network’s Maria Bartiromo.

Citing warnings from Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, who has repeatedly warned that cybersecurity threats pose the biggest risk to national security, Hayden said that Apple was “technologically correct when they say doing what the FBI wants them to do in this case will make their technology, their encryption, overall weaker than it would otherwise be.”

“This may be a case,” he added, “where we’ve got to give up some things in law enforcement and even counterterrorism in order to preserve this aspect, our cybersecurity.”

“Any effort to legislate, or to use a court, to stop this broad technological trend just isn’t going to work.”

Apple is fighting a court order directing it to write custom code that would let the FBI flood the iPhone used by one of the San Bernardino shooters with password guesses, eventually enabling the bureau to unlock the device. The company and its supporters, including Silicon Valley firms, civil-society groups, and cryptography experts, argue that Apple’s compliance would open the door to increasingly dangerous demands for technical assistance.

James Comey, the FBI director, has staunchly defended the government’s position in the fight, which is part of a larger war over whether tech companies should design their encryption so that they can bypass it for investigators. Hayden urged Congress not to pass legislation that would weaken encryption, like mandates that companies add so-called “backdoors” to their security.

“Any effort to legislate, or to use a court, to stop this broad technological trend just isn’t going to work,” Hayden said. “We are going to a world of very high-end encryption that will be used routinely by people around the planet.”

Some outside observers have questioned whether the NSA, which employs the world’s most powerful computers and its most experienced code-breakers, could simply bypass the encryption protecting the San Bernardino iPhone and let the FBI search for the evidence it’s seeking. Hayden told Bartiromo that he doubted this was possible, saying, “If the NSA had it within its ability to act with FBI authorities to get inside that phone, you and I would not be having this conversation.”

Hayden’s arguments against backdoors—which set him apart from the vast majority of current and recently departed national-security officials—mirror those advanced by security experts and privacy advocates.

“If we legislate against” strong encryption, he warned, “a second- and third-order effect will be to drive the world’s best encryption off-shore.”

A recent study found that foreign companies, which would be unaffected by a U.S. backdoor mandate, produced 63 percent of identified encrypted products.

Hayden added an argument that privacy groups generally leave out: That U.S. investigators can still glean certain information from encrypted communications by looking at its metadata—including when it was sent, by whom, and from where—even if they can’t decrypt the full communications. That ability, he warned, would disappear if investigators were forced to reorient to new foreign platforms.

“All that other stuff, which I call your and my digital exhaust, that digital exhaust won’t be available to U.S. law enforcement,” he warned.

Hayden argued that the answer to the encryption problem was to increase funding for federal agencies working to secretly and quietly break it, not to put the onus for bypassing it on the private sector.

If Hayden were still in government, he said, he’d be thinking, “I’ve got to aggressively develop new machines that allow me to break that code, not [insist] that Apple break it for me.”

Screengrab via Fox Business Network