Facebook is changing. Surely you’ve noticed. Your best friends are getting buried beneath memes; your mom is getting pushed aside by image spam. Your social graph is becoming secondary to your interest graph.

Worried about competitors like Tumblr and Twitter, and urgently in need of new revenue flow following its rocky IPO, the biggest social network in the world is drifting away from its social core.

Say hello to the new Facebook. You won’t find many people here. But you will find a lot of trash.

![]()

In 2006, Facebook was still just an upstart. Sure, Mark Zuckerberg’s dorm-room creation was making waves in the burgeoning online social space, but it looked like a measly little brother compared to Myspace and its 100 million users. Facebook had just 8 million at the time, most of whom were college students.

Then in early September the game changed. Facebook released a new feature called the “newsfeed,” a central hub that collected every update from your friends in one place. Prior to this, you had to go through the laborious process of visiting friends’ profile pages to see what they were up to. But here was everything everyone was doing in one place: relationship updates, likes, comments, photos. You could sit down with the newsfeed open all day and never miss a thing. It did to your social life what RSS did to blogs.

Despite the name, the feature really had very little to do with “news,” at least not in the way CNN or the New York Times would use the word. Here’s how Facebook’s official blog described it at the time (emphasis ours):

News Feed highlights what’s happening in your social circles on Facebook. It updates a personalized list of news stories throughout the day, so you’ll know when Mark adds Britney Spears to his Favorites or when your crush is single again. Now, whenever you log in, you’ll get the latest headlines generated by the activity of your friends and social groups.

For Facebook, “news” just meant “what your friends are up to.”

Most sites are built on a short-term contract with readers: They show you something or perform a service for you and maybe, if you like it enough, you’ll keep coming back. Facebook was building its empire on a much stronger bond: real relationships.

It paid off. The newsfeed quickly made Facebook the most addictive social network, and users snowballed: 16 million by the end of 2006, 50 million by 2007, 350 million by 2010, and finally, 1 billion in 2012. Facebook soared as its competition, Myspace and Friendster, wilted and died.

Even today, Facebook’s users spend more time on the site than any other top Web destination in the world, thanks in part to those strong bonds: six hours and 41 minutes, according to Nielsen. That’s four hours and 30 minutes more than its nearest competitor.

Your average Facebooker spends 40 percent of those six hours glued directly to their newsfeed.

![]()

It was only a matter of time until scammers found out a backdoor to your newsfeed. We’ve called the phenomenon “content spam,” and it works a lot differently from the Viagra and diet pill emails you’re used to.

The formula is easy, if somewhat labor-intensive: Find a successful image or meme elsewhere on the Internet (Reddit, for instance), then repost it to your Facebook page. Since the images are proven online hits, they perform well on Facebook, too, and you quickly amass a huge following.

Soon the spammers start sneaking in links to external sites, all filled with the exact same stolen images, only this time slapped with advertisements. There are thousands of pages like this. Pretty much every top entry on the “people talking about” (PTAT) list at independent analytics firm Page Data, for instance, works on this model. (PTAT measures engagement on Facebook, and provides the best indication of the virality of a page’s content).

Maybe you’ve seen their names ooze into your newsfeed? Teen Swag, Stylish Eve, Dresses, Shut Up I’m Still Talking. These pages reach tens of millions of followers every day. Those people, in turn, like and share each other’s content, ensuring even newsfeeds get clogged with their fluff.

The future of Facebook in one image. Facebook’s mission is to “make the world more open and connected.”

It’s a serious quality problem. And it’s only one symptom of Facebook’s bigger malady.

Just about every organization in the world is trying to carve out a living space in the newsfeed ecosystem, from spammers and professional news organizations to charities and trolling misogynistic jerks. It’s a Darwinian battle for attention, and the pages who succeed become highly evolved social media beasts whose posts routinely rack up tens of thousands of likes and thousands of comments. Take, for instance, juggernauts such as I F*cking Love Science, with its 5.4 million followers, or Upworthy, the viral media aggregator (whose backers include Chris Hughes, a Facebook cofounder) that has amassed more than 1.9 million followers in little more than a year thanks to an almost exclusive focus on calibrating content for maximum sharing on Facebook.

Your friends can’t compete against that.

When friends’ posts do show up in your feed, a lot of times they’re just sharing another image or link or video. External content, i.e., stuff that isn’t native to Facebook (memes, articles, pretty science photographs), is the network’s new social currency. Facebook is mutating into a social media hydra, a bit like Twitter, which dominates live events (Facebook even experimenting with hashtags) and a bit like Tumblr, which rules entertainment and fandom. The only problem? Those companies are already the very best at what they do, and to compete against them Facebook has to dilute the highly personal network of real relationships that makes it unique.

Soon you’re going to start judging Facebook friends on how good they are at sharing stuff—not on their actual relationship with you.

You choose to subscribe to pages, but their content is starting to push your friends out of the way. Is that in Facebook’s best interest?

![]()

From their beginning, pages were an explicit part of Facebook’s advertising platform, even if it wasn’t yet clear how the company could earn money from them. Personal profiles had always been strictly restricted to real people, and businesses were chomping at the bit to finally start making inroads on the world’s largest social network.

Released in 2007, pages were the solution to that problem. “Facebook Pages expands the social graph by enabling brands, businesses, celebrities, and other entities to have a presence on Facebook,” the company wrote when announcing their launch. But in the years since, that final category, “entities,” expanded to included just about anything you can imagine. Pages are platforms for anyone to build a an audience about anything.

Whether you were a professional content creator, amateur, or spammer, if you ran a successful page you became addicted to all of that free attention. Facebook started to recognize a significant advertising opportunity.

Whether you were a professional content creator, amateur, or spammer, if you ran a successful page you became addicted to all of that free attention. Facebook started to recognize a significant advertising opportunity.

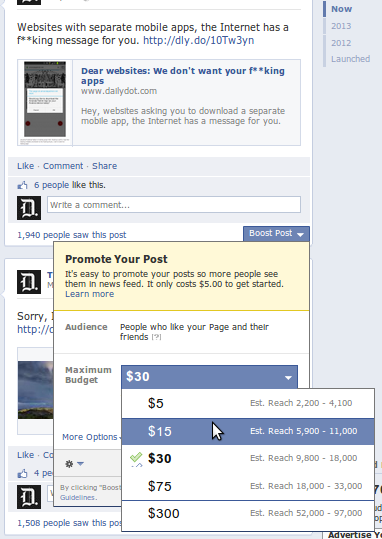

The way to monetize was easy: The company tightly controlled the gate to a users’ newsfeed in order to limit noise; usually brands only reached 15 to 20 percent of their followers with a single post. Enter the “promoted posts” feature in May 2012. For a small fee, Facebook said, it would help you reach even more people than usually do. Depending on much you paid, you could reach that remaining 80 to 85 percent. The bigger your page, the more the service would cost.

It was a solution for two problems: Facebook’s sidebar ads have historically performed very poorly, and what’s worse, they don’t even show up on mobile devices, to which most users are migrating. Because promoted posts showed up in your newsfeed, they partially solve this mobile advertising dilemma.

A few months later, page owners noticed a precipitous drop in engagement, as much as 63 percent. It seemed like Facebook was throttling engagement to press page owners for whatever they could, though the company claimed it was all a coincidence. Yes, the algorithm changed right after announcing promoted posts, and yes many people noticed huge drops on their pages, but engagement as a whole actually increased by 34 percent, Facebook said.

You’ll have to take their word for it. Everyone from the New York Times‘ Nick Bilton to George Takei and Mark Cuban noticed a significant drop in how many followers they reached with every post.

The pay-to-play controversy seems to have barely registered on Facebook’s radar. It’s doing everything it can to remind page owners they can pay to reach their audience, plastering a glaring “boost post” button at the bottom of every post. To increase followers, Facebook urges you to pay for ads that will hover next to newsfeeds: Pay to add followers, then pay again to reach them!

Just a few months after Facebook rolled out the promoted posts feature, COO Sheryl Sandberg boasted that more than 500,000 pages used it, 70 percent of whom became repeat customers. There are more than 60 million pages on Facebook. Suffice to say, the company has just started to squeeze them for cash.

Pages are as important to Facebook’s future as people.

![]()

Earlier this year, a hoodie-draped Mark Zuckerberg took the stage in a tightly choreographed press event to announce the reinvention of the newsfeed. Everything was going to be bigger now, he declared: Images, videos, ads, link previews. The feed would become a lush media experience.

“We want to give everyone in the world the best personalized newspaper in the world,” Zuckerberg said (emphasis ours).

That’s a tremendous departure from how the company described the newsfeed in 2006. Back then, it was just a place just for your friends. Now Facebook’s most important feature, its bloodline, is just a dumping ground for anything that exists on the Internet.

It makes sense, to a certain extent. Many of the fastest growing social companies over the past few years thrive on shareable media: Twitter, Tumblr, Pinterest, Instagram. The fact Facebook was willing to drop close to $1 billion for the latter—far more than most analysts believed the photo-sharing startup was worth—shows just how panicked the company really feels about its rich media competitors.

This slow metamorphosis into a different type of social network is a big risk for Facebook. The strong bonds you have with friends are becoming overwhelmed by the weak ones you form with anonymous strangers.

That might be good for jacking short-term pageviews, but it’s not the basis for a very healthy long-term relationship.