Last week, news broke about a psychological study conducted by Facebook researchers that once again set the Internet talking about the ways the company controls users’ data, invades their privacy, and, in this case, actively tries to alter their moods without knowledge or consent beyond standard “terms and conditions.”

The study was published in Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), using the Facebook data of over half a million users to show “experimental evidence that emotional contagion occurs without direct interaction between people.”

Facebook researchers altered the News Feeds of users as part of an experiment looking into whether people’s moods could be affected by the content they view. The experiment set out to find whether the moods of study “participants,” and I use that word loosely, could be affected by changing the number of posts with positive or negative emotional content in news feeds.

All gross misconduct aside, it’s understandable why Facebook executives would want to look into how the social network affects people’s moods. After all, the point of the social network, like most consumer products, is to make its customers happy and coming back for more.

But another psychological paper published in the June 2014 issue of Computers in Human Behavior shows that Facebook might already be well behind the curve where their customers’ mood is concerned.

The title of the paper says a lot: “Why Facebook causes a decrease in mood and why people keep using it.”

Two Austrian psychologists, Christina Sagioglou and Tobias Greitemeyer, ran three studies for the paper and found that, while users log on to Facebook expecting to elevate their moods, Facebook significantly decreases mood by giving people a sense that their time on the site was meaningless.

Sagioglou and Greitemeyer’s first study investigated the emotional state of Facebook users after they had browsed the site. They used a “common validated mood questionnaire” that looked into the moods of users who had been “actively using” the site for over 20 minutes. According to the study’s methodology section, “active usage” involves posting pictures, chatting, or browsing Facebook friends’ profiles.

Findings of this study indicated that the longer users stayed on Facebook, the worse they felt.

The second study of the paper looked into several control measures. In short, results showed that participants’ decrease in mood didn’t occur when they were just browsing the Internet, only when they were on Facebook. Furthermore, the second study found that this mood change stemmed from participants being affected by “a feeling of not having done anything meaningful.”

The third study conducted by the researchers for the paper looked into the popularity of Facebook. As in, why does the social network continue to be so popular, when it so demonstrably bums its users out? These surveys found that people keep coming back to Facebook, because they expect their moods to be elevated, even though the opposite actually occurs.

Given the conclusion of Sagioglou’s study, one can’t help but wonder whether Facebook had already cottoned on to the deleterious effect of Facebook on its users’ psychological well-being, and whether Kramer’s mood study was looking into ways to counteract this. It would certainly make sense from Facebook’s point of view.

In Kramer’s apology for the PNAS paper, he cited “the common worry that seeing friends post positive content leads to people feeling negative or left out” as one of his team’s motivations. And this is a phenomenon that has already been looked into in a 2012 paper titled “‘They are happier and having better lives than I am’: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of other people’s lives.” Another telling title.

From that paper’s abstract, published in psychological journal Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking:

The multivariate analysis indicated that those who have used Facebook longer agreed more that others were happier, and agreed less that life is fair, and those spending more time on Facebook each week agreed more that others were happier and had better lives.

I exchanged a few emails with Dr. Sagioglou, the lead researcher on “Why Facebook causes a decrease in mood and why people keep using it.”

Daily Dot: How do your findings fit in with other studies of the same sort? Is there a consensus among the psychological community concerning Facebook’s effect on users’ moods?

Dr. Sagioglou: There cannot really be a consensus yet, because there haven’t been many experiments conducted that examined users’ mood. It is quite conceivable that some activities have a negative outcome on users’ mood, while others may increase one’s mood.

Browsing through other people’s profiles, for example, seems to be one of the activities that dampens our mood, while more directed FB behavior such as chatting and organizing an event or one’s studies may have positive effects.

The third part of your study gets to the motivation of why Facebook continues to be so popular, given that the net emotional effect on users appears to be negative.

In your opinion, why do users keep coming back to the site? You mention expectation of positive emotions as a factor. But given that your study shows people experience negative emotions after Facebook use, why haven’t they learned better?

It is kind of hard to answer this question. Motivation has always been a big question in psychology and often [provides] complex answers.

I think that a few factors lie at the core of a continued FB use. People may expect that FB satisfies some basic human needs, like the need to control our social environment or the need to belong. But eventually FB doesn’t do a good job at it.

If you’re really hungry, for example, and eat two chocolate bars, you won’t be hungry afterwards but you’re not necessarily happy either, because you’ve just eaten something very unhealthy. It may very well be that users go online, get some important things done, but then stick around on FB, which eventually feels like a waste of time.

Are you familiar with the recent PNAS Facebook study that has made the rounds in news lately? What do you think about this team’s methodology? What do you think of the public’s negative response to the study?

Yes, I am familiar with this paper. I can understand the public’s reaction to it. After last June, this shouldn’t surprise anyone. However, [this] doesn’t make it any more ethical the way users’ were “informed” by FB about their data being collected.

Given that browsing people’s profiles are shown in your study to be one of the activities that dampens Facebook users’ moods, how does that finding clear with Kramer’s findings that seeing “positive content” produces positive mood via “emotional contagion”?

In the study Kramer et al.’s report in PNAS, they did not specifically measure people’s mood. They looked at the content of people’s posts as a consequence of manipulated news feed posts. This may not necessarily reflect users’ overall mood, but just the selection of their current emotional state that they decide to share on Facebook.

At first, these study may seem to show diverging results, but human emotions are so multicausally determined that each finding reveals just one facet.

Are you on Facebook? Why or why not?

I was on FB but deactivated my account many years ago, because I felt like it was a waste of time and didn’t do anything that other ways of communication couldn’t achieve just as well and easily.

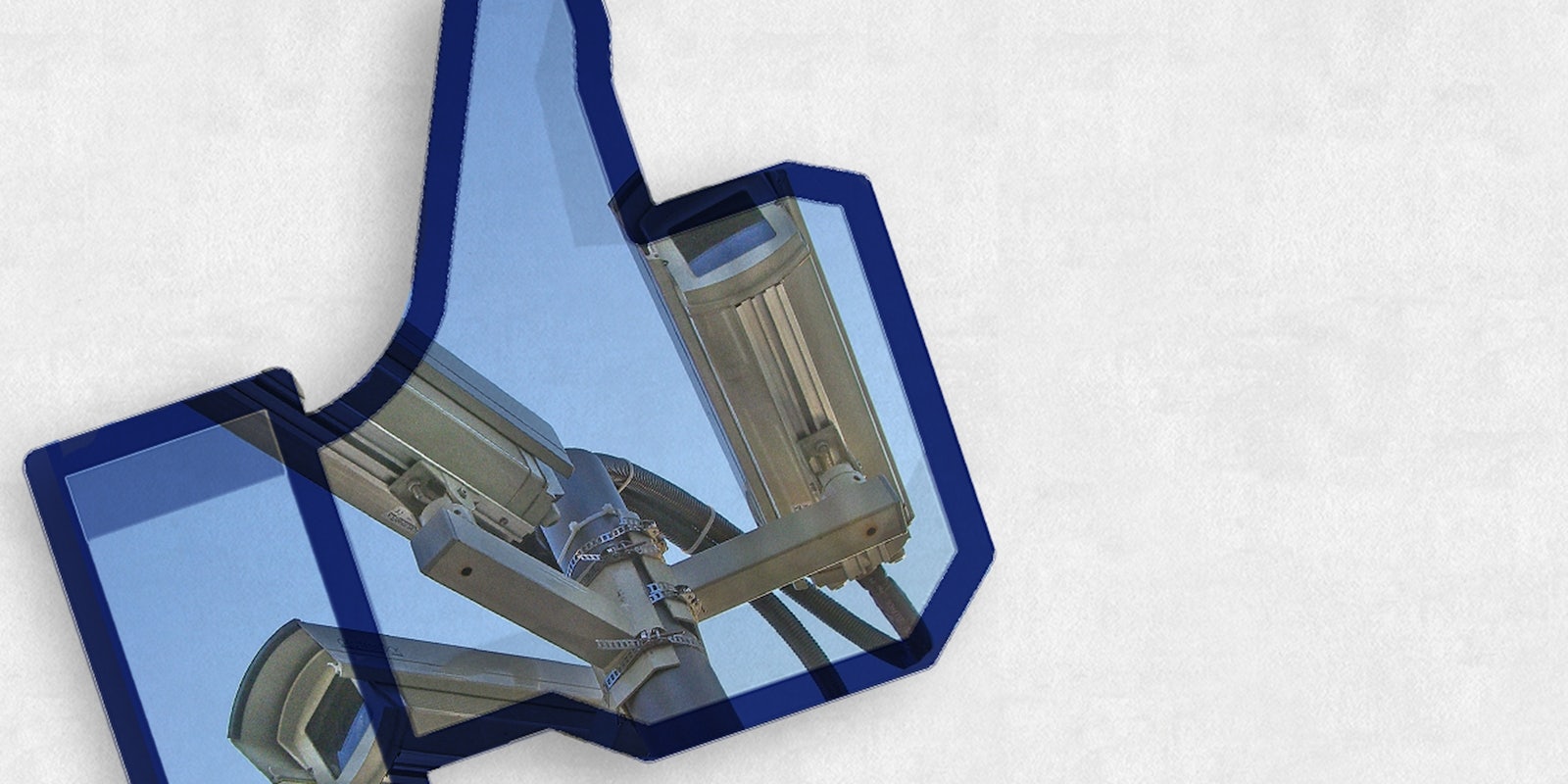

Photo by CBS_Fan/flickr (CC BY SA 2.0) | Remix by Fernando Alfonso III