When Comcast, the largest cable company in America, announced earlier this month it intended to buy Time Warner Cable, the second-largest cable company in America, pretty much everyone was angry.

Both Comcast and Time Warner Cable are two of the most disliked companies in America. There’s widespread fear that the combined entity will use its monopoly power to screw over everyone from content providers like Netflix to everyday Internet users.

Comcast CEO Brian Roberts had an interesting response to this criticism: The deal won’t hurt competition, he essentially said, because there’s already no competition.

He told Reuters: ?[The deal] will not reduce competition in any relevant market because our companies do not overlap or compete with each other. In fact, we do not operate in any of the same zip codes.”

This statement is actually pretty shocking.

Comcast and Time Warner are the biggest Internet service providers (ISPs) in the country. Together they serve more than 30 million customers. Time Warner serves communities in 29 states and Comcast provides broadband to customers in over 40.

There is no regional bent to each company’s territory—both operate in markets scattered across the country. Yet, there is not a single instance of the two companies even attempting to directly compete against each other, as Roberts admits. How is that even possible?

With high-speed broadband Internet service, actual competition is the exception rather than the rule. A report released last year by the Washington, D.C.-based New America Foundation argued that this lack of direct, local competition has a profoundly negative effect on both the speed and affordability of the country’s broadband Internet service.

“Our data also shows that the most affordable and fast connections are available in markets where consumers can choose between at least three competitive service providers,” the report charged.

?Only nine percent of Americans have access to three or more providers; the majority are limited to one or two incumbent telephone or cable companies.”

How this state of affairs came about is a matter of both history and economics.

?When cable was first getting started, it was thought of as a natural monopoly with high up-front costs [required to set up the core network infrastructure] and relatively low marginal costs [for signing up each new user],” explained Doug Brake, a policy analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

As with other services viewed as natural monopolies, such as Ma Bell-era AT&T, governments across the country signed deals granting companies exclusive rights local rights. But, in return, they’d have to take actions that served the interests of the greater community, like agreeing to host public access channels.

Municipalities selected cable providers based on which one paid them the most money. In the early 1990s, Congress outlawed these types of exclusive deals, which had the effect of enshrining these local cable monopolies into law. However, by then, it was already too late to really foster local competition because the infrastructure had already been built.

Cable companies were able to take this infrastructure, initially built to transmit TV signals, to cheaply and easily transform themselves into Internet service providers.

In the ensuing decades, the dozens of small cable companies that sprung up around the country consolidated into four telecom behemoths—Comcast, Time Warner Cable, Charter Communications, and Cox Communications. Comcast acquired 10 other cable companies on its path to regional dominance. For its part, Time Warner Cable gobbled up seven. The companies’ only two major competitors, Charter and Cox, are each the product of mergers between approximately a dozen previously independent firms.

The most intense merger and acquisition period occurred in the late 1990s, in what’s been termed the ?Summer of Love.” Largely orchestrated by telecom executive Leo Hindery, who ran AT&T’s broadband efforts, the summer saw a series of partnerships that, according to telecom industry blog FierceCable, ?put every market in the United States except four into the hands of a single operator.”

Maintaining the status quo and respecting each other’s boundaries works very well for the incumbent cable providers. They’re able to retain all the benefits of being a monopoly in a given market without having to worry about maintaining that monopoly nationwide. Sure, ISPs lose out on being able to attract large swaths of new customers. But it’s a lot easier for them to maximize revenue from the customers they do have.

Chris Mitchell, a director at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, argued that the combination of the cable companies’ decades-long head start and widespread industry consolidation has created a situation where new entrants have no hope to compete in established markets.

?To build a network in St.Paul, Minn., where I live, it would cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $200 million,” Mitchell explained. ?To get that together you’d have to raise all the capital required and then pay back those loans. Since Comcast is so big, it could cross-subsidize from other markets and just temporarily lower rates to the point where it was selling service below cost to drive their competitor out of business.”

As a result, competition doesn’t usually come in the form of cable. There’s DSL, often offered by the local phone companies. But since it’s largely run over copper phone lines, the speed of Internet over DSL typically lags behind that of cable. It’s a similar story with satellite Internet—although, to be fair, even American DSL and wireless Internet achieve faster speeds than what’s available in most countries in the world.

The other option is fiber-to-the-home Internet offered by Verizon’s FIOS service and Google Fiber. However, neither of these options are particularly viable for most Americans. According to the New America Foundation study, FIOS offers customers far more high-speed bang for their buck than what most cable giants have put out there. But the company only rolled out the service in a small handful of markets and said it has no future plans expand the program outside of the few major metropolitan markets where it currently exists.

Google Fiber, on the other hand, is expanding. Only a few days after the announcement of the Comcast-Time Warner Cable deal, Google announced it plans to bring its lightning-fast Internet service to eight new cities including Portland, Ore., San Jose, Calif., and Nashville, Tenn.

However, Google’s service isn’t replicable everywhere. ?Many municipalities see the cable franchise as a revenue opportunity…Google Fiber turned this process on its head, and instead played municipalities against each other to see which would give it the best deal,” explained Roslyn Layton, a tech policy analyst at the American Enterprise Institute.

?Kansas City offered Google the best deal with a tax holiday, free rent, free electricity, use of the telephone poles to hang the fiber, and so on.”

So Google was able to shop around for the best deal among city governments, many of whom were clearly looking for the PR boost that comes from getting the company’s blessing. But Google’s also been allowed to pick and choose which neighborhoods it would offer its service, ensuring the highest rate of adoption.

While Google Fiber may not exactly be a workable model for everyone in the U.S., there is some evidence that injecting additional competition into the wired broadband market has positive effects for consumers. In recent years, there’s been a growing push for local governments around the county to invest in their own municipal broadband networks. Ephrata, a small farming community in rural Washington state, has a municipal network built and owned by a local public utility district but operated by a small, private ISP. Its Internet is the fastest Internet in the country,

Mitchell, whose organization is a strong advocate for municipal broadband, explained how a new competitor coming into a previously cloistered market has the potential to do wonders for consumers.

?When Lafayette, Louisiana built its municipal fiber-to-the-home network, Cox Cable initially insisted that it was providing fine service,” he said. ?But, in the run-up to the municipal network’s roll-out, Cox didn’t raise rates in Lafayette, although it did hike prices four times in neighboring communities.”

Mitchell added that Cox also started distributing the next generation of cable modem in the community quite early—usually major cities are the first to get new technologies, not small towns like Lafayette.

Even so, Brake, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation analyst, warned against assuming that municipal broadband is the solution to local cable monopolies. These projects do well in providing Internet connections. But they also often attempt to branch out into cable television, and that’s when things can get a bit dicey.

?A lot of the smaller networks that succeed do so because they don’t offer TV—just phone and Internet,” Brake said. “Because securing the rights to carry TV content is unexpectedly expensive…and increasingly so.”

Brake, who is generally in favor of the merger, said one potential benefit of tying Comcast and Time Warner Cable together is that the newly enlarged firm would command a larger share of the market. That means it might be able to negotiate better rates from media companies, particularly when it comes to live sports. Those are by far the most expensive content on cable, because they’re one of the few bits of TV programming that the overwhelming majority will watch live. Savings from those deals, Brake argues, which could eventually be passed along to consumers.

However, if the deal goes through, it seems unlikely those reduced costs are going to trickle down any time soon. “The impact on customer bills is always hard to quantify,” Comcast executive Steve Cohen told BGR during a conference call shortly after the merger announcement. “We’re certainly not promising that customer bills are going to go down or even increase less rapidly.”

If the government allows the merger to go through, Comcast might end up getting a better deal on content but not pass along those savings to consumers. But if customers are unhappy about that, they won’t exactly be able to find another provider. Undoubtedly, that’s the way Comcast likes it.

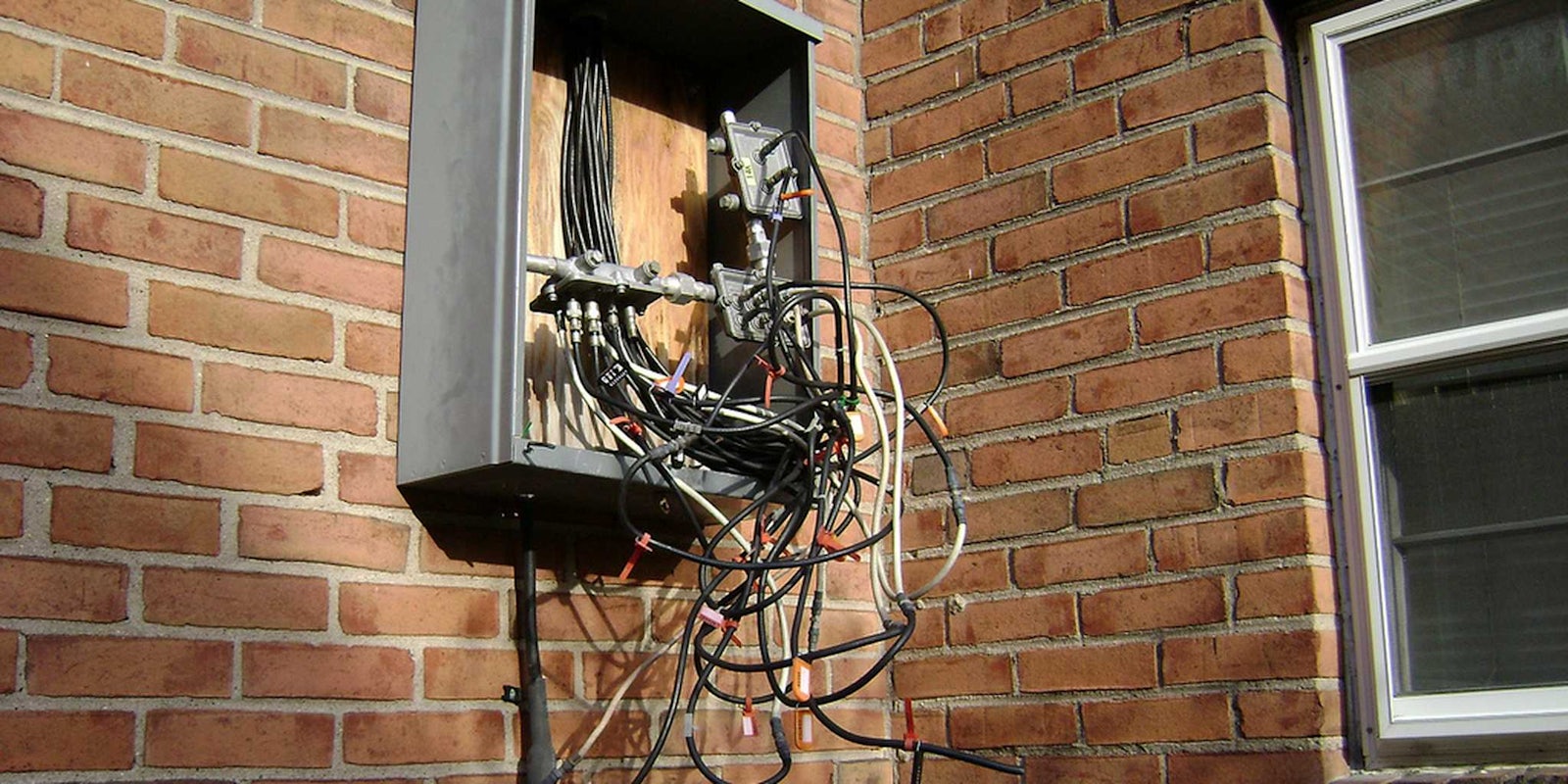

Photo by Douglas Muth/flickr