Working on a Marvel comic is a dream for many and a nightmare for some, an opportunity that lets you play with iconic superheroes while also becoming a target for vitriolic harassment.

Mockingbird writer Chelsea Cain experienced the harsh side of this on Wednesday, driven off Twitter by abusive comments from fans who disliked the feminist message of her work.

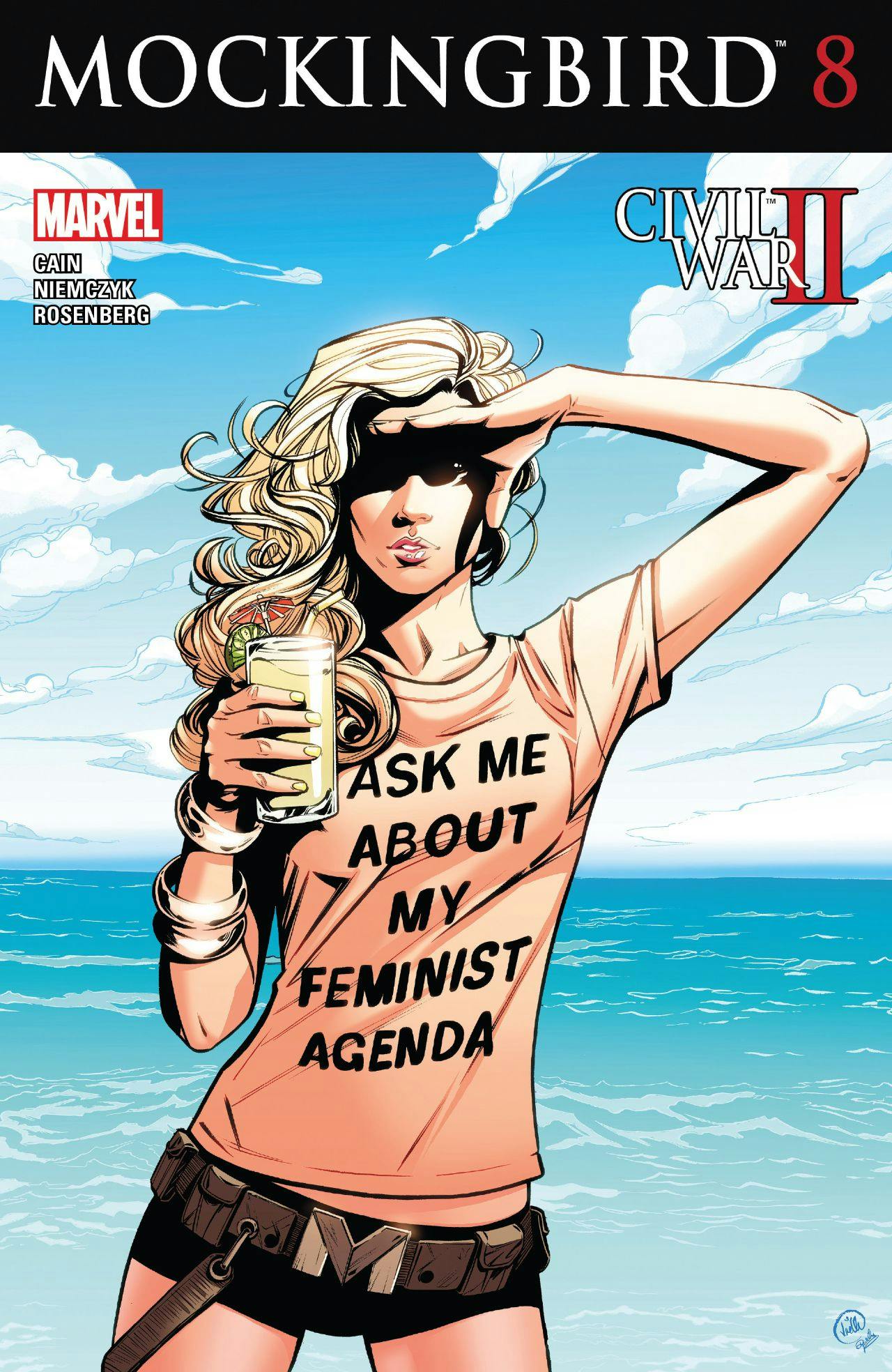

Better known as a bestselling author of prose fiction, Chelsea Cain was recruited by Marvel to write Mockingbird from March to October 2016. The comic was cancelled this month, and its final issue featured cover art with the slogan “Ask me about my feminist agenda.”

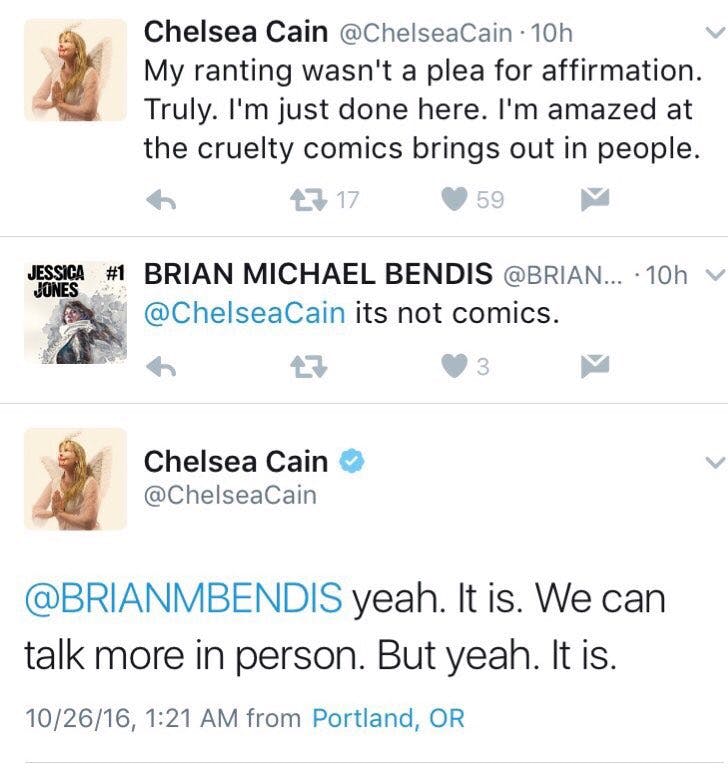

This cover, drawn by Joelle Jones, provoked a barrage of unpleasant messages to Chelsea Cain on Twitter. In a series of tweets that have since been deleted with the deactivation of her account, Cain wrote, “I’m in my office dealing w/ misogynist bullies on Twitter” instead of spending time with her 11-year-old daughter, adding, “I’m just done here. I’m amazed at the cruelty comics brings out in people.”

Brian Michael Bendis, one of Marvel’s top writers, responded with a tweet that some fans interpreted as him “mansplaining harassment” to Cain, although he later said it was misconstrued, and they are friends.

While many communities have a harassment problem, Cain is correct in saying the comics industry stands out. In an earlier tweet, she also pointed out that she never had to block anyone on Twitter before Mockingbird, which has a tiny audience compared to her novels.

Marvel and DC have both faced numerous public scandals regarding harassment and sexual assault, and we’re currently witnessing a culture war between people who want superhero comics to represent a more diverse range of characters and creators, and those who don’t. This has led to controversies like the recent criticism of sexualized cover art for Marvel’s new Iron Man, and women receiving rape threats for sharing their opinions about comics online.

I #StandWithChelseaCain not because she wrote a great book–which she did–but because there’s no excuse for online harassment. None.

— Giant Waterbear (@giantWB) October 26, 2016

Following Cain’s disappearance from Twitter, several fans highlighted a quote from Marvel Editor-in-Chief Axel Alonso: “I’m the last thing from a social justice warrior.”

The quote comes from an interview about Marvel’s push to diversify its cast with characters like Amadeus Cho, the new Hulk. However, Alonso’s use of the phrase “social justice warrior” is significant because it’s widely regarded as a dog-whistle term, a pejorative popularized by Gamergaters mocking feminists online. By distancing himself from so-called SJWs, Alonso was (perhaps unintentionally) sending a message to the kind of trolls who would unironically use that phrase to describe Chelsea Cain.

Alonso has since pledged his support for Cain, but not before comics Twitter launched into yet another conversation about sexism in the industry.

(Ed Brubaker wrote superhero comics throughout the 1990s and 2000s, best known for creating the Winter Soldier. He has since moved on to write for Image Comics, which allows its creators to retain legal ownership of their work, unlike Marvel or DC.)

So getting something trending or all over Tumblr is nice and all. But if everybody went to ComiXology or wherever and bought Mockingbird #8

— Tom Brevoort (@TomBrevoort) October 27, 2016

…that would be a much more potent statement about what you want in your comics. And you can do it from this device you’re looking at now!

— Tom Brevoort (@TomBrevoort) October 27, 2016

Marvel editor Tom Brevoort and Captain America writer Nick Spencer both argued that the best way to support writers like Chelsea Cain is to buy their books.

https://twitter.com/nickspencer/status/791379017769201665

https://twitter.com/nickspencer/status/791380101296328704

But this “vote with your wallet” strategy is more complicated than Spencer and Brevoort suggest. If women creators are driven off social media, it’s harder for them to promote their books and increase sales. If publishers continue to employ known harassers, fans may boycott their books regardless of content, thus sending the “wrong” message. And if—to take one recent example—a team of middle-aged white men is hired to write a comic about a black teen girl, there’s a good chance they’ll do something to alienate readers.

Meanwhile, there’s a massive untapped audience for queer superhero fanfic and art, and people are throwing money at indie comics by women on Kickstarter. The most popular cartoonist in America is Raina Telgemeier, whose comics are aimed at 12-year-old girls.

Marvel and DC can’t have it both ways. Either they can proactively discourage harassment and promote a more diverse pool of creative talent, or they can placate the kind of fans who think “SJW” is an insult. It’s understandable for a corporate entity to be motivated by sales, but it’s equally understandable for fans and creators to avoid an increasingly toxic industry.