I’m the last person in the world to decry a good Twitter parody account. The Mayor Emanuel Twitter handle, launched during Rahm Emanuel’s election bid for the mayorship of Chicago, was a lesson in brilliant dadaist surrealism that caricatured Emanuel’s penchant for profanity and grandiosity and ensconced it in an alternate reality so absurd that it transcended mere satire.

I can also appreciate Twitter parody accounts that peddle in inside baseball. I never knew much about longtime New York Observer editor Peter Kaplan, but that didn’t dissuade me from following the two parody accounts, each reflecting opposite ends of his personality, run by former staffers of his: Wise Kaplan and Cranky Kaplan.

And perhaps some of the best Twitter accounts out there are those that don’t parody a specific person, but rather satirize an entire demographic or cultural phenomena. BuzzFeed’s Ryan Broderick recently profiled several teenagers who have launched an entire network of parody accounts, many with names like Tweet Like a Girl and Common White Girl, that have amassed millions of followers, propelled by the humor derived from common experiences and observations.

But there’s another kind of parody account that’s gained traction in recent years, one that, in my opinion, skirts Twitter’s rules about running impostor handles and aims to deceive the users who retweet and follow it.

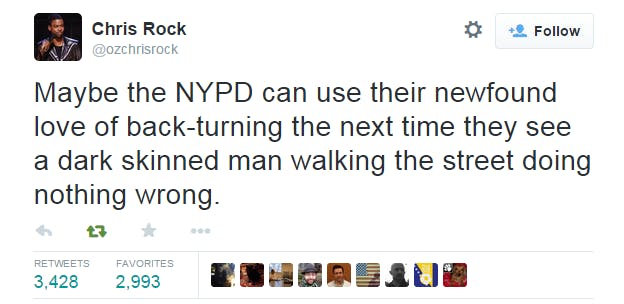

In late December, in the wake of the brutal murder of two NYPD officers by the gun of a deranged anti-cop killer, I saw a tweet supposedly from Chris Rock retweeted into my stream:

The tweet was just the kind of biting observational humor that fans of Chris Rock have come to expect, and it latched on to the haunting racial dynamics that have plagued the New York Police Department and the minority targets of its stop-and-frisk initiatives. It also mirrored my own complicated feelings about how the NYPD had reacted to Mayor de Blasio’s rhetoric on law enforcement racial profiling. So I retweeted it.

A more insidious form of impersonator has begun to emerge.

Then, curious to see more of Chris Rock’s tweets and possibly follow him, I clicked through to his profile. It was only then that I discovered that this was not, in fact, Chris Rock tweeting, but what was described in the bio as a “parody account.” Perusing through the handle’s tweets, however, I saw nothing that resembled any sort of parody. Rather than caricaturing Rock, pushing his personality through a prism that magnified his absurdities, the account merely mimicked his progressive comic sensibilities—it was an imitator, not a parody, and for that imitation it had generated close to 80,000 followers. There’s no doubt that many of those follows and the hundreds of thousands of retweets came from users like me who had been duped into thinking we were reading the words of Chris Rock.

Twitter as a company has long understood the negative implications of impostor accounts. In 2009, once the social network began to achieve mainstream success, it was plagued with celebrity impersonators who regularly duped the media and millions of users into following them. That year, the media exploded after an account claiming to represent the Dalai Lama appeared on Twitter, and it attracted thousands of followers in a matter of days. Soon, however, it was reported that the account was a fake, and Twitter quickly stepped in to suspend it.

A year earlier I had outed a D.C. consultant who had been running an account that purported to be Republican pollster Frank Luntz. Like the Chris Rock account, the Luntz Twitter handle gave no indication that it was a parody and often tweeted mundane observations like what he happened to be eating. The account was regularly retweeted by beltway insiders who had no idea they were promoting an impersonator. “It’s actually kind of scary,” Luntz told the Washington Post after the fakery had been revealed.

The problem got so bad that Twitter introduced verified accounts in mid-2009 as a way for celebrities to battle the cadre of impostors that had been buzzing around them like flies. Twitter continued to swat down those flies and the verified checkmark badge allowed celebrities to tweet with some level of security and their fans could follow with assurance that the accounts were the real deal.

But while the most blatant impostors were zapped, a more insidious form of impersonator began to emerge, one hiding under the banner of “parody” to mask its real intention: capitalizing on the celebrity of others in order to amass followers and influence.

Case in point: the Twitter handle for Bill Murray. Sporting the handle @biIImurray (those are two uppercase I’s disguised as lowercase L’s), it has amassed nearly a half a million followers. Like the Chris Rock account, it offers a disclosure on its profile (“I AM NOT BILL MURRAY. This is a parody account”), but also like the Rock account, nothing it tweets resembles parody. It is merely a series of one-liner jokes, some corny, others actually funny. And because of the way Twitter is designed, seeing these jokes retweeted into your stream in no way reveals that they’re coming from a parody account, so you can be excused if you retweet to your followers what you think are the actual words of Bill Murray.

They’re capitalizing on the celebrity of others in order to amass followers and influence.

“What’s the harm in this?” you may ask. Well, for one, you have a writer who is cashing in on Murray’s career and brand, a brand he spent decades erecting. There’s a reason why I can’t publish a novel while claiming to be Stephen King, just as there’s a reason I can’t begin releasing designer bags and slapping the Gucci logo on them.

The account is also blatantly unethical in another sense: it’s a serial plagiarist. Take any of its one-line jokes and plug them into Google and you’ll find they originated somewhere else, yet the fraudster who runs the account gives no credit or any indication that he didn’t originate the joke. The most recent tweet about cellphone photos, for instance, had originated at least two months prior on other accounts.

So you have an imposter who isn’t Bill Murray who’s tweeting out jokes that neither he nor Murray wrote, and for those troubles he’s tricked hundreds of thousands of people into following and retweeting an account many of them believe is run by Bill Murray. Given that Twitter hasn’t stepped in and banned the account, this person could easily profit from these followers by running sponsored tweets and linking to off-site content.

The plagiarism is a consistent theme on these parody accounts. I won’t bore you by listing them all, but I’ll point you to one more: an account with the handle @thereaIbanksy. That handle alone should render its claim to be a mere “fan account” absurd, but no, it not only continues to exist, but it’s also gathered nearly a million followers for its troubles.

And in case you’re wondering, no, it doesn’t actually appear to be a fan account of Bansky the street artist at all. Very few of its tweets have anything to do with Banksy, but rather they’re of uncredited artwork and quotes with no quotation marks or citations. Google any of the tweets it offers up and you’ll find that not a single one contains any sort of originality. This is an account that has flourished merely for its name and for no actual inherent talent, unless you consider shameless theft a talent.

I realize that Twitter walks a fine line when it tries to discern impostors from parodies, and that removing parodies at the request of those they satirize would have a chilling effect on free speech and criticism, but it seems obvious to me, based on the examples above, that these accounts are flaunting Twitter’s rules against impersonation by offering up ludicrously thin disclosures. The barrier for entry for a parody account should not exist within the fine print, but instead should be painfully obvious in its manner and impact. These accounts don’t even begin to meet that threshold.

Simon Owens is a technology and media journalist living in Washington, D.C. This article was originally published on his personal site. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, or Google+. Email him at simonowens@gmail.com.

Illustration by Jason Reed