Making people laugh can be a pretty unfunny business.

The latest comedian to reveal as much is Emmy-winning Whose Line Is It Anyway? star Wayne Brady, who opened up this week about his serious and ongoing battles with depression. “It starts this cycle where you tell yourself these lies … and those lies become true to you,” the master improviser told Entertainment Tonight. “So, you stick to your own truth you’ve set up. ‘If I am this bad, then why should any of this matter?’ I feel at that point, you end up wanting to stop the pain.”

That Brady has decided to open up after the passing of Robin Williams, who also suffered from depression, is no coincidence. Brady had performed with Williams during the late actor’s guest appearance on Whose Line, and was unsurprisingly in awe of his raw comedic talent. “When he was on stage [in] full-on Robin mode—and I know this from being blessed enough to work with him—you could not touch that man,” said Brady, “He made all these people feel great. And at the same time, knowing that he had this sense of…what I make up in my mind, this low sense of self-worth, of belonging, of loneliness, of pain that all the money in the world can’t cure, all the accolades and awards, and all the love from people all over the world…all that love could still not stop that man from saying, I am in so much pain.’”

Brady picked the right time to come out about his depression, not just because of the attention Williams’ suicide has brought to the issue, but because it’s always the right time to come out about depression. Though it’s sad to think about in retrospect, Williams himself talked about how important it was to reach out to people if you’re hurting. However, Brady has now also forced us to return to a conversation may be hard to have. The truth is that many comedians have fallen victim to serious depression, now matter how difficult it is for our society to think of them in that way. And with the added pressure of the digital age, the constant demand to perform makes this issue more challenging than ever.

The link between comedians and depression is not exactly a secret. In their book, Pretend the World is Funny and Forever: A Psychological Analysis of Comedians, Clowns, and Actors, renowned psychotherapists Seymour and Rhoda Fisher examined over 40 professional comedians before arriving at the conclusion “that a major motive of comedians in conjuring up funniness is to prove that they’re not bad or repugnant.”

More recently, Dr. Peter McGraw at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Humor Research Lab conducted an online study asking people about their perceptions of comedians to find that 43 percent of participants believed there’s something wrong with most of them, while 34 percent believe most comics are “messed up” in one way or another. Heck, by now it’s such common knowledge that comedians often tend to be on the depressive side, L.A.’s Laugh Factory offers therapy sessions for comics twice a week.

Furthermore, anybody who has paid the slightest attention to actual comedians knows how deeply depression is threaded into the profession. From Lenny Bruce to Woody Allen, Rodney Dangerfield, George Carlin, and Richard Pryor, it’s on display for everybody to see in the so-called “greats.” Then there’s the many comics whose depression fed into substance abuse (a factor in Williams’ case, too), and vice versa, which thereby resulting in overdoses. John Belushi, Sam Kinison, and Chris Farley might all fall into this category. Moreover, Wikipedia literally has a whole page devoted to “comedians who committed suicide.”

However, in the wake of Williams’ death, and even the years preceding it, an increasing number of comedians have also opened up and talked freely about depression. There’s Stephen Fry, Conan O’Brien, Ellen DeGeneres, Louis C.K., Sarah Silverman, Jim Carrey, Patton Oswalt, and David Letterman, to name a few. This is a very good thing, as talking about depression (while not guaranteed to solve anything permanently) shows other people it helps to talk about depression, too. Because until you talk about it, people don’t know what you’re going through.

Illustrating exactly that, a Rolling Stone piece following Williams’ suicide by comedian and writer Dana Gould included an anecdote about the late comic genius, where Gould revealed, “I remember thinking that this man, who had a career like no one could ever hope to dream of, stand-up success, sitcom success, movie stardom, he’d even won an Oscar, and yet, he was humble, gracious, sincere, caring. He knew where happiness lay. He, who had so much, still knew what was important and what was not. ‘This guy,’ I thought, ‘he’s really got it together.’”

This is the fundamental tragedy about comedians and depression. Everybody sees it, everybody knows it, yet when we’re faced with the reality of it, we are unable to comprehend. Gould himself, a fellow comedian, thought Williams really had it “together.”

In the same piece, Gould also notes, “Five of my friends and fellow comedians have taken their own life. It’s shocking, but, sadly, not surprising. Non-comedians—or as we call them, “civilians”—are always surprised… Being funny is not the same as being happy.” What Gould is getting at here is that the we tend to think of comedians as being larger than life can be harmful, as sometimes they’re among the meekest, most sensitive people around.

Case in point, this January, Oxford University’s Professor Gordon Claridge conducted a study which found that “comedians tend to be slightly withdrawn, introverted people who may not always want to socialise, and their comedy is almost an outlet for that.”

Cracked’s David Wong expressed a similar sentiment after the news about Williams broke. Wong wrote, “When I hear some naive soul say, ‘Wow, how could a wacky guy like [insert famous dead comedian here] just [insert method of early self-destruction here]? He was always joking around and having a great time!’ my only response is a blank stare. That’s honestly the equivalent of ‘How can that cow be dead? She had to be healthy, because these hamburgers we made from her are delicious!’”

Wong backs up the notion that most funny people suffer from mental health issues, breaking the journey down from being different or scarred or just plain depressed during childhood, to discovering that laughter can put a bandage on that. “In your formative years, you wind up creating a second, false you—a clown that can go out and represent you, outside the barrier,” he asserts. “The clown is always joking, always ‘on,’ always drawing all of the attention in order to prevent anyone from poking away at the barrier and finding the real person behind it. The clown is the life of the party, the classroom joker, the guy up on stage—as different from the ‘real’ you as possible. Again, the goal is to create distance.”

“You do it because if people hate the clown, who cares?” he continues. “That’s not the real you. So you’re protected. But the side effect is that if people love the clown…well, you know the truth. You know how different it’d be if they met the real you.”

So as Wong sees it, comedians don’t exactly use humor “to prove that they’re not bad or repugnant,” as the Fishers settled on. According to Wong, they use humor because they know they are bad and repugnant, and humor is a way of masking that.

The only problem with this is that for some, this line of thinking can glamorize the idea of the “tortured artist.” Or to put it another way, the negative side of talking about depression and great comedians is that a person could get the idea that you need to be depressed if you want to be a great comedian.

But despite all the very good points made by Gould and Wong, this isn’t necessarily the case. In April, Slate ran an article that explored Dr. McGraw’s Humor Research Lab, and the conclusions they came to were fascinating.

According to McGraw’s theory of humor, the benign violation theory, humor arises when something seems wrong or threatening but is simultaneously OK or safe… To test his theory, McGraw recruited grad student Erin Percival Carter and Colorado State University professor Jennifer Harman to run an experiment in which they had 40 people come up with a short story they might tell to others at a get-together. Half were asked to recount a funny story while the others just had to be entertaining. Among the humorous stories were tales of a dog swallowing a box of tampons, a guy getting caught singing in the men’s room to Cyndi Lauper’s ‘Time after Time,’ and someone deciding one drunken night to let a buddy burn a lightning bolt into his forehead so he’d look like Harry Potter… So perhaps comedians aren’t much more disturbed than anyone else—they’re just in the business of telling the world about their foibles.

So maybe the truth isn’t so much that comedians are depressed, as much as it is that comedy itself is depressing. Or maybe it’s a chicken and the egg thing. Or maybe the very act of over-analyzing something like comedy and the people who work in it is folly. Either way, it’s important to recognize that a) depression is real, and whether someone is funny or not has nothing to do with it, and b) depression is not something to aspire to, and any artist who has dealt with it would probably be happy to tell you that personally (if they’re still here, that is).

Unfortunately, the one other thing we know for sure is that the Internet does not help with this. In fact, if anything it hurts. Consider that although Williams’ death ushered in a reinvigorated conversation about mental health online and throughout the rest of this country, we were all momentarily distracted from that by the bottom-feeding trolls who temporarily drove his daughter of Twitter. Wong also talked about how harmful this kind of behavior is for all creative people, especially those prone to depression, writing, “do you want me to tell you how many messages/comments/emails we get from fans telling a writer to “kill yourself” because said writer wrote a joke they didn’t like? When I ban them, they always act confused as to why.”

Wayne Brady discussed how he identified with Williams in terms of the pressures of being a comedian. “When you have a job like this,” he said, “and when you’re someone like Robin…people really aren’t interested for the most part in you having a regular outlook on something. So, the joy that you carry with you onstage, you’re supposed to carry with you even in real life… he [Robin] was always on, for everyone. Because that was what was expected.”

Now think about that expectation, of always being “on,” and compound that with the pressures of maintaining an online presence. Comedians are now expected to craft an Internet-friendly brand for themselves, in addition to working on their actual stage material. On one hand, this makes things easier, as it allows you to reach a wider audience. But where it becomes more difficult is in the constant pressure that not just comedians, but all of us are under to perfect a digital image of ourselves.

When Patton Oswalt took a vacation from social media in June, he mentioned, “Constantly feeling like I have to have an instant take on things.” We’ve already seen the negative impact that being online has had on many celebrities; it’s no wonder that a comedian like Oswalt would feel crushed by the demand to always be “on” when he’s online. Of course, this demand would weigh heavily on anyone, but for comedians, who are expected to be not only insightful and interesting, but also perpetually witty, this pressure is at a fever pitch.

Perhaps sad comedians aren’t a big deal to most people. Perhaps we should all just agree that depression is “no laughing matter,” then have a good chuckle anyway, and move on with our lives. But the next time depression takes one of our favorite comedians, or someone we work with, or a close friend, or a family member, chances are we’ll wish we’d taken mental health issues a little more seriously.

Ideally, comedy can be used as a tool to deal with anything, including depression. Nevertheless, we have to keep discussing it anyway, on the Internet and everywhere else. Brady’s struggles represent not only the struggles of Williams and many other comedians, but of many Americans and people around the world in general. Laughter is good medicine, but we musn’t forget that a killer stand-up routine doesn’t solve a person’s deeper problems.

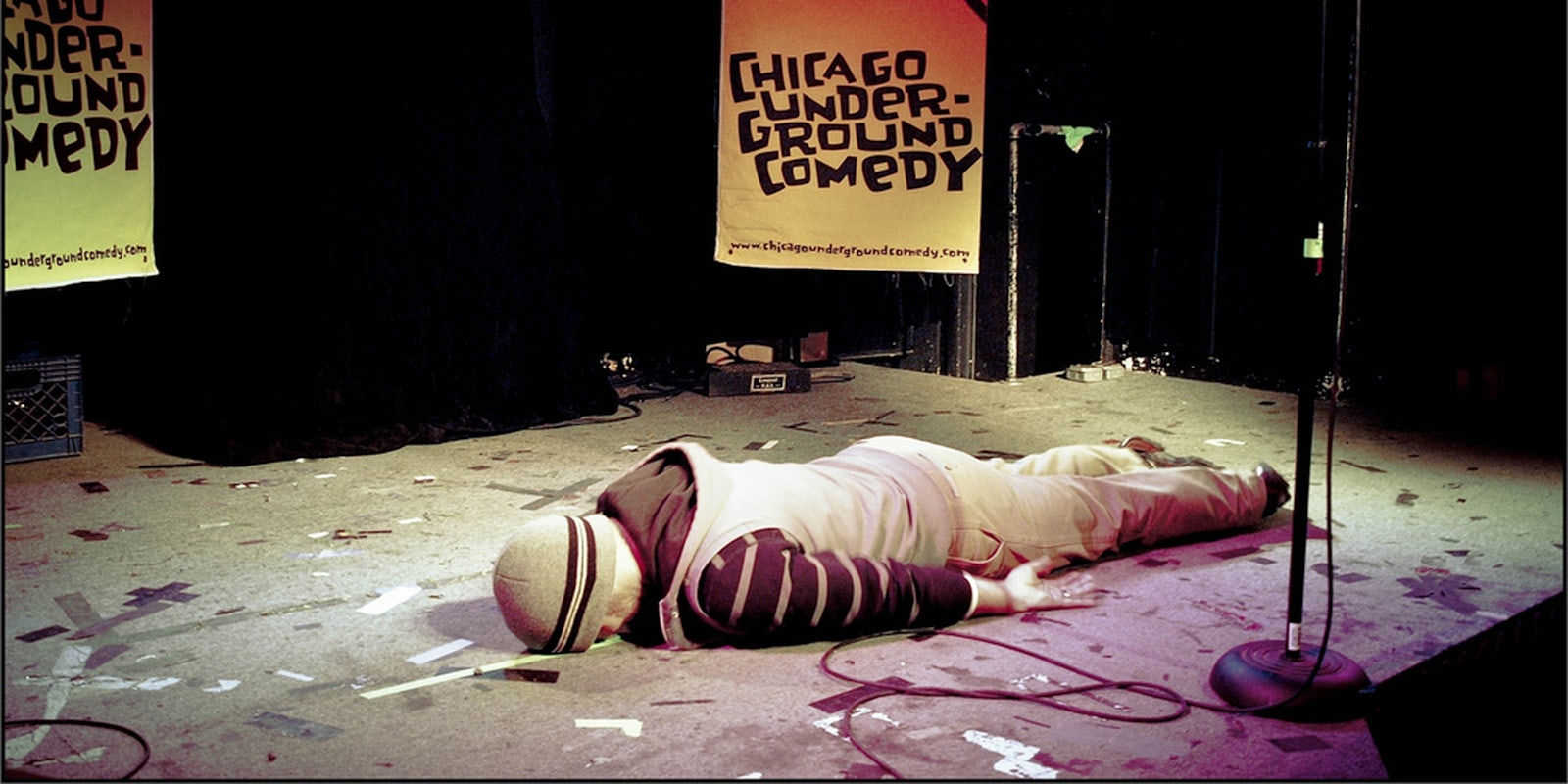

Photo via TheeErin/Flickr (CC BY S.A.-2.0)