Homelessness in America is generally on the rise and a number of cities are dealing with large populations of chronically un-housed people. This has resulted in a number of state and local problems, including disease outbreaks, local governments spending huge amounts of money with little result, and even violent attacks.

This attack is monstrous, but it was not random. It targeted the most vulnerable among us.

— Julián Castro (@JulianCastro) October 5, 2019

It is our failure to treat people experiencing homelessness with dignity that left these individuals vulnerable to such hateful violence. https://t.co/0gLAdHVIwd

But homelessness in America has also developed a number of myths and misconceptions that make it difficult to separate fact from fiction. As with any large-scale problem, much of what is believed and passed around about the homeless is either untrue or no longer accurate. And it drives policy decisions and baseless fear in wealthier communities.

Here are some of the most prevalent myths about homelessness in the U.S.

Homelessness myths, debunked

Has homelessness increased in the United States?

According to data from the National Alliance to End Homelessness, “between 2017 and 2018, homelessness increased slightly by 0.3 percent or 1,834 people.” But since 2007, when the Department of Housing and Urban Development began keeping track, homelessness has actually dropped about 15 percent overall, with larger drops among veterans and families.

Do most homeless people sleep on Skid Row?

It’s a popular perception that most major cities have some kind of run-down tent city where the homeless are more likely to congregate. But this has largely changed other than in Los Angeles, where the original infamous Skid Row originated.

Even in L.A. County, the homeless population is about 59,000—with only about 4,800 on the city’s Downtown Skid Row. Many other large cities have bulldozed or gentrified what was once their Skid Row, including New York and Chicago. A large portion of people without proper shelter either live in suburbs, rural areas, or in their cars—not in a centrally located part of town.

Common myths about the homeless in LA:

— Lexis-Olivier Ray (@ShotOn35mm) June 4, 2019

1. They’re not from here (almost 70% of all the homeless have lived in LA County for 10 years)

2. They’re mostly on drugs and mentally ill (70% are not)

3. They create most of the trash (illegal dumping is the biggest cause of trash)

Are most homeless individuals mentally ill?

In 1963, the U.S. embarked on a large-scale closing of long-term psychiatric institutions, resulting in many of these individuals becoming homeless—and leaving nowhere for these people to go since then. Subsequent studies have found that while homeless people are more likely to suffer from severe mental illness, mental illness is not one of the overall leading causes of losing one’s housing. Between one-quarter and one-third of the homeless population likely has some form of mental illness, but U.S. mayors generally believe that long-term joblessness, poverty, and lack of affordable housing are the top initial causes of homelessness.

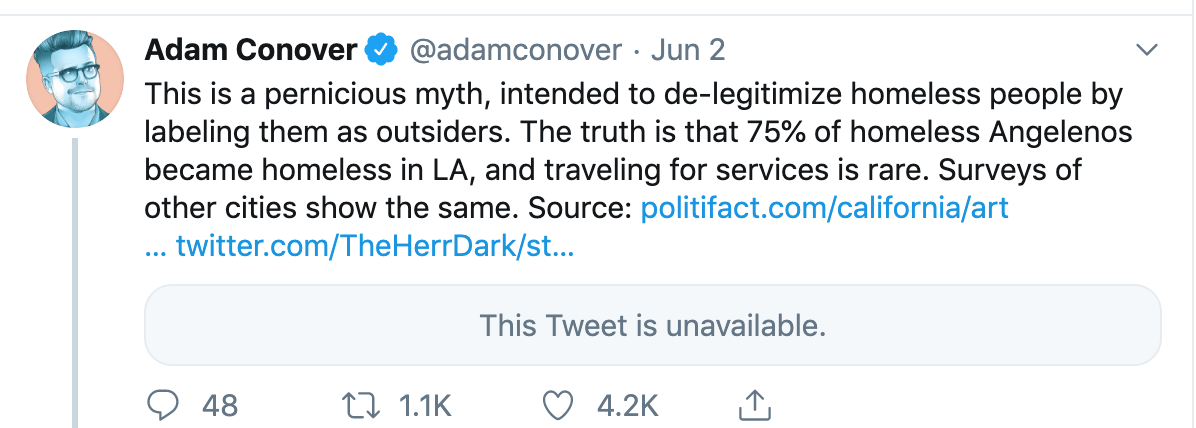

Do homeless people typically move to warmer climates to live on the streets?

Not generally.

For 2018 in San Francisco, about 70% of people identified as homeless were also longtime residents of the area. The numbers are similar for L.A. County, where about 65% of homeless people have resided there for more than 20 years. New York City has the highest individual homeless population of any city, and even states with the most extreme cold weather have some population of people without adequate shelter.

The higher proportion of homeless in California is almost certainly due to housing prices, rather than an influx of people from out of state.

Are most homeless people addicted to drugs or alcohol?

Homelessness and substance abuse are often intertwined, with one leading to or worsening the other. But overall, only about 26% of homeless have a serious drug problem, with a slightly higher percentage having a similar problem with alcohol. For the general population, studies show about 8-9% of adults dealing with substance abuse. So the number in the homeless population is higher, but not a majority.

Do most homeless people choose to be homeless?

The idea that homelessness is a popular choice among people who refuse to work is a powerful one. In response to the sharp uptick in American homelessness in the 1980s, President Reagan claimed in 1984 that “the people who are sleeping on the grates … the homeless … are homeless, you might say, by choice,” and added in 1988 that the people sleeping on benches just a few hundred yards from the White House “make it their own choice for staying out there.″

But when offered the opportunity to obtain permanent housing, the majority of homeless people readily take it. Other studies have found that homelessness increases every time a city sees major rent increases—showing that losing one’s home is far more often a consequence of high rents, rather than a choice.

Are most homeless people on the street because they refuse to work?

The myth that a homeless person will be shamed into getting their life together by yelling “get a job” at them is undercut by statistics.

In one 2018 survey, 13 percent of homeless people in San Francisco report having a part or full-time job. Other studies have found that about 44% of the homeless did some kind of paid labor during a 30-day period, and about 55% worked during the year while they were homeless. Many chronically under-housed people, living on someone’s couch or in a shelter, work two or three jobs—with none paying enough to remedy their situation. In many cities, it would take over 100 hours of minimum wage work per week to make median rent.

Homeless Mom Works Three Part-time Jobs While Living in a Skid Row Homeless Shelter https://t.co/umMacKAMjs

— Invisible People ➤ Imagine Everyone With a Home (@invisiblepeople) August 17, 2019

Is homelessness permanent?

According to a 2014 HUD survey, about one-in-six homeless people have been on the streets for over a year. The typical duration of homelessness is usually a few days.

Do homeless shelters or low-income housing depress the value of nearby properties?

Housing prices in areas with large-scale services for the homeless generally remain high. While areas directly near these housing units do sometimes see upticks in minor crimes like loitering, overall, they don’t see plummeting home values—and many have active gentrification going on.

There’s no data that shows the building of homeless shelters or affordable housing in a highly-populated area has any overall negative impact on the residents there.

READ MORE:

- GoFundMe for homeless opera singer raises more than $20K (updated)

- Florida city is pushing homeless people out by playing ‘Baby Shark’ on a loop

- HUD proposal would allow homeless shelters to refuse trans people