Think about your day-to-day routine: When you get to work in the morning, when you end up at your favorite bar, what route you take home, and so on. We often lose sight of these patterns in the daily blur of life, but if you tracked your personal data for a year, would you notice a distinct rhythm or cadence to your day? Brian House did.

House teaches part-time in the Design and Media program at Rhode Island School of Design. For two years, he was also on staff at the New York Times’ Research and Development Lab, where he helped develop OpenPaths, a mobile app that collects personal geographic data, then creates a visual map of where you’ve been, which you can share or keep to yourself. House tracked his movements around New York City and beyond for a year.

“OpenPaths works in the background, so you really forget about it,” House told the Daily Dot. “And then you look at the map and see the trace of all those narratives, and it is striking. … What’s surprising is really how much I did adhere to patterns, in ways I wasn’t really aware, such as how late I stayed out or how often I left the city, and how going through the city I tend to travel clockwise.”

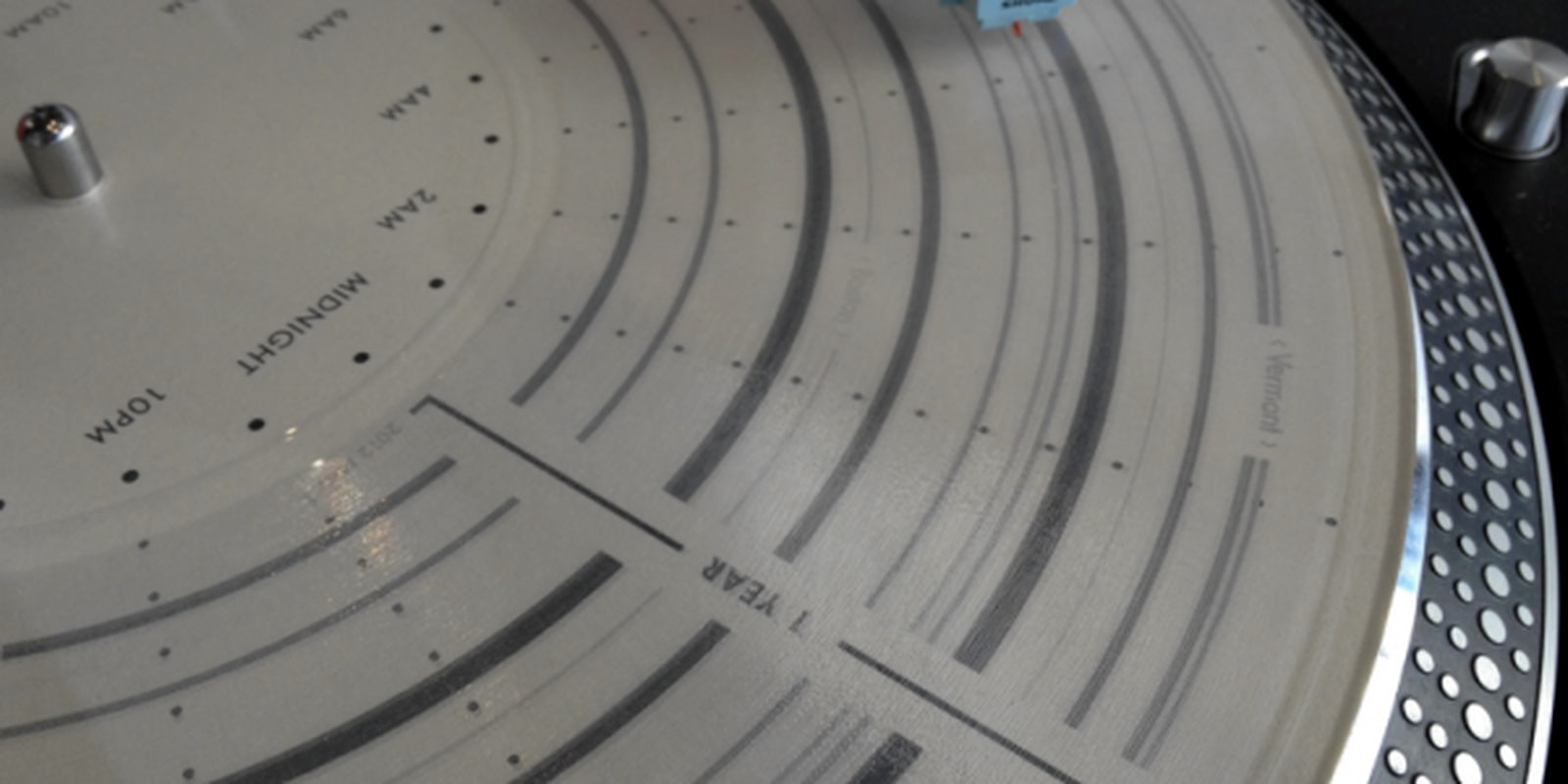

House is also a musician, and decided rather than feeding the data into a computer program, he would make it a participatory experience. He narrowed down the locations he frequented most often, then pressed 365 days of data into 365 rotations on a record. One day equals one rotation. He called it “Quotidian Record,” and produced it as an 11-minute limited-edition LP.

“I think that the way we move in the world is inherently musical,” House says. “And that all music reflects that. Everyone can relate to music, musician or not, and I’m interested in finding new ways to utilize that capacity.”

The goal of OpenPaths is twofold: to give users ownership over their personal data, and to encourage artists, researchers, and other creative minds to analyze data differently. As the National Security Agency continues its mass collection of info, House finds it troubling that some people don’t care who’s collecting their data.

“People don’t seem to connect with the idea that this goes beyond individuals with ‘something to hide,’ but affects the texture of daily life,” he says. “Whether it’s corporations building an advertising profile on you, individuals looking to hire you or date you, or the NSA evaluating your potential as a terrorist, personal data are increasingly defining, and increasingly inescapable. And we have to reckon with that. And in an art context, one way is to find alternative means of relating to data, ways that are not about classification and commodification and control but which emphasize embodiment and subjectivity and expressivity.”

Photo via Brian House