My first job was in retail. As a wild and fun-lovin’ deeply insecure teenager, I may or may not have let an acquaintance of mine, one that I evidently wanted to impress, talk me into giving him a heavy discount on a new video game. So I might have nervously and ruefully broke the law. If I was caught, my name would probably have been entered into a gigantic private database, and I would never have worked in retail ever again. I just might not have known why.

The New York Times has a front-page investigation into this massive database, called Esteem. It is operated by the First Advantage Corporation, which tracks workers who have been accused of stealing from their employers. “Facing a wave of employee theft,” the Times reports, “retailers across the country have helped amass vast databases of workers accused of stealing and are using that information to keep employees from working again in the industry.”

Note that right there: “accused of.” Not “convicted of.” Not “charged with.” Now carry on: “The repositories of information … often contain scant details about suspected thefts and routinely do not involve criminal charges. Still, the information can be enough to scuttle a job candidate’s chances.”

The story details the travails of 28 year-old Keesha Goode, who was accused—never charged or convicted—by her employer, the discount store Forman Mills, of failing to ring up a former employee’s goods at the cash register she was operating. She says she did no such thing, but was coerced into signing an admission form by management under threat of legal action—she was fired, and her name went into the database.

Now Goode can’t get a job in retail because potential employers, who pay to access that database, see that she has been accused of theft. Or aiding theft. Or whatever the text in some tiny blinking box says she did that has rendered her permanently untrustworthy. Kyra Moore, who was also accused by her employer, CVS, of stealing, has the following description listed in the same database: “picked up socks left them at the checkout and never came back to buy them.” For this she was fired, and is now permanently deemed unemployable in retail thanks to a sprawling digital blacklist.

What I did as a seventeen year-old was way worse than either. I too should have been deemed a menace to the retail industry and ineligible for any future job. Maybe I still will be after this article is published. For me, a privileged, middle-class college-bound white kid, that wouldn’t have been the end of the world. I could always find other summer jobs—I was a privileged white kid, after all. But millions of people depend on retail jobs to pay the rent and put food on the table. They don’t have that luxury. And the fact that they can be blacklisted from a job by a dumb transgression when they were a teenager—or, as we’ve seen for doing nothing at all—is disturbing.

Read the full story on Motherboard.

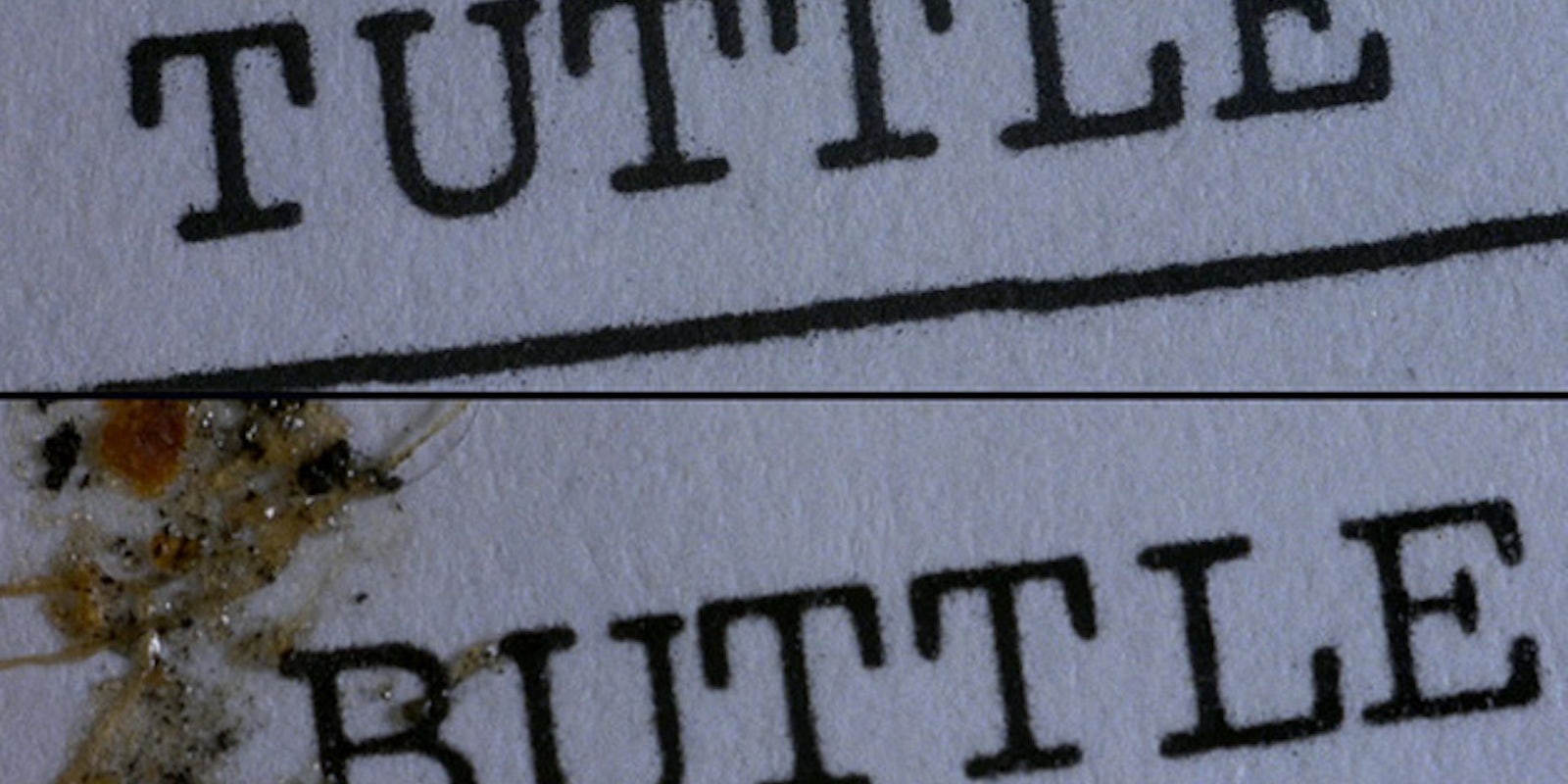

Screenshot via Brazil | By Brian Merchant