Have you ever looked at an ad Google’s running alongside your search engine and thought that it was rather racially explicit in nature? Is your name Chase, Logan, D’Antrel, or Destiny? If so, the mere fact that Google knows your name may have something to do with the way those ads are showing up.

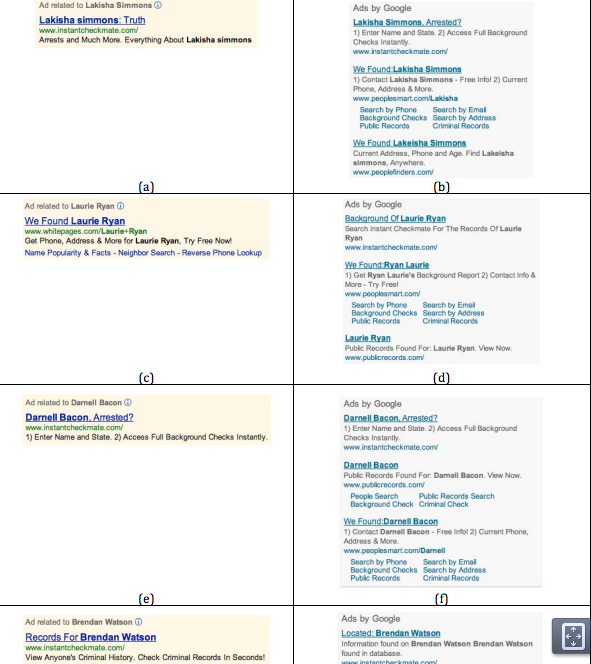

According to a study performed by Harvard University government and technology professor Latanya Sweeney, there’s an alarming trend going on online in which Google’s pay-per-click ads were showing a somewhat skewed pool of racially charged results. Titled “Discrimination in Online Ad Delivery,” Sweeney’s study suggests that Google is more likely to return a background-check advertisement if you search a name that could be categorized as traditionally black (Sweeney cites such names as DeShawn, Marquis, Kenya, Terrell, and Tamika as such possibilities) rather than those that are traditionally white. For the latter, Sweeney found, Google was more likely to send searchers to a White Pages result.

Naturally, the whole hypothesis reeks somewhat of subjective studies and superbly skewed perspectives, but Sweeney was quick to point out that she’d done her part to put the research on a proper playing field.

“From Sept. 24 through Oct. 23, 2012, I searched 2,184 full names on google.com and reuters.com,” she wrote. “Execution took place at different times of days, different days of week, with different IP and machine addresses operating in different parts of the United States using different browsers. I manually search 1,373 of the names and used automated means for the remainder.”

Through that, and among many other things (all of which are detailed on page 20 of her study), she found that “ads for public records appeared more often in black names than white.”

“Regardless of company, proportionately more ads appeared for names having a black-identifying first name,” she wrote. “PeopleSmart ads appeared for 270 white and 280 black names, being disproportionately higher for blacks, 41 percent to 29 percent. PublicRecords ads appeared 10 percent more often for black than white names, and Instant Checkmate ads 2.45 percent more often for blacks.”

Sweeney closes by conceding that the study raises more questions than it answers, but it can conclude one item for certain: “Our hypothesis states that no difference exists in the delivery of ads suggestive of an arrest record based on searches of racially associated names. Our findings reject this hypothesis. A greater percentage of ads having ‘arrest’ in ad text appeared for black identifying first names than for white identifying first names in searches on Reuters.com, on Google.com and in subjects of the sample.”

You can read the study in full—all 35 pages—right here.

Photo via Spencer Holtaway/Flickr