As Napoleon Bonaparte and what remained of the Grande Armée retreated from Moscow on Oct. 19, 1812, the sun shone brightly. When he departed the city, the French Emperor declared: “Look how fine the weather is. Do you not recognize my star?”

Those seemingly minor details from the French invasion of Russia may have been consigned to history if not for a hardy researcher who’s recounting incidents from that year in real time.

Fernando Souza is using Twitter to trace the events of 1812, including that year’s major military conflicts, albeit with a 200-year timeshift. The Twitter account for the project, @1812now, shares details about “all types of facts and people” from political figures and soldiers to writers and regular people.

“When I thought of doing a feed about the year 1812, I knew that I would have to deal with military events,” Souza, 47, told the Daily Dot.

“In 1812 you cannot ignore the War of 1812 or Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. At the same time, I wanted the feed to include other aspects of the past. I wanted the feed to try and capture something from each day two hundred years ago.”

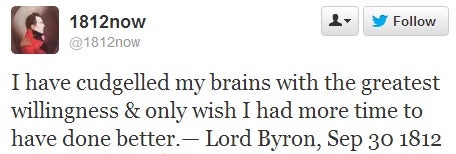

The tweets cover a broad range of life in 1812. Notes from Lord Byron sit alongside reports from the War of 1812.

As time has progressed, Souza told the Daily Dot, he realized the most compelling way to share the past was to tweet out “excerpts from letters or diaries written two hundred years to the day.”

Souza studied history at the University of Toronto, a city in which he still resides. He’s always had an interest in the topic, particularly in the areas of intellectual, political, and literary history.

A commercial litigation lawyer, Souza trawls through original documents scanned and placed online, biographies, and history books to find compelling facts and stories to share. His favorite tweets so far relate to “the diary of Martha Ballard (a New England midwife), excerpts from the journal of Aaron Burr, and the letters of Thomas Jefferson and Lord Byron.”

His accompanying blog offers context and some historical documents related to the tweets. So, for instance, for a tweet about Ludwig van Beethoven’s first meeting with poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Souza crafted a blog post with more detail about that rendezvous.

He tries to keep the content of the tweets to the point; it’s actually the blog that takes up most of his time.

“A tweet cannot bear too much information,” Souza said. “If it does, readers tune out. Even when there are a set of tweets describing an event, each tweet ideally should be sufficient unto itself to convey one idea or image.”

Souza was inspired to start work on @1812now after discovering @RealtimeWWII, which tweets about events from World War II as closely as possible to the time in which they occurred 72 years prior. He thought that he could do a similar feed for 1812. It’s like Trivial Pursuit unfolding on Twitter.

Of course, it’s a little more difficult for Souza to tweet events close to the time they occurred since “in most cases, the actual time—in terms of the hour from 200 years ago—is simply not known.”

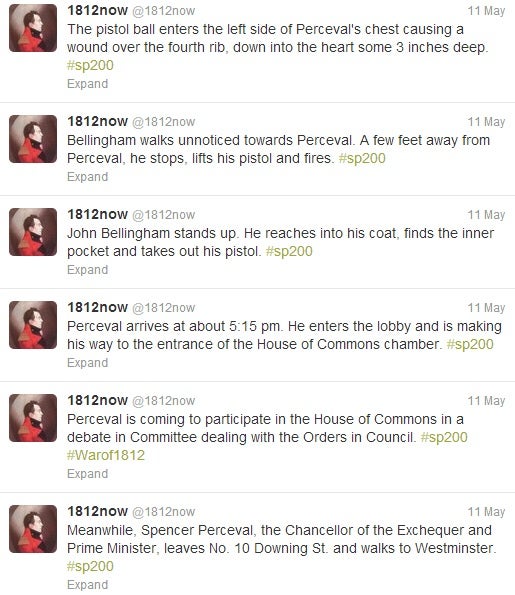

Still, he has managed to make space to tweet and blog every day so far this year. Souza was also able to provide consistent updates on the assassination of British Prime Minister Spenser Perceval on May 11 as it might have happened a couple of centuries back.

When writing his tweets, Souza attempts to do so as if he has no knowledge of an incident’s outcome. Occasionally, he’ll flout the self-imposed rule by “adding hashtags that provide a different context to what is stated in the main part of the tweet.” Rich media like videos and photos are sometimes placed into tweets for further context.

Souza, who is considering continuing the project into 1813 (next year), admitted to being surprised that the “Russian Embassy in London started tweeting my Napoleon tweets.”

Such an event shows just how much has changed in 200 years, both in politics and technology.

Photo of Napoleon Bonaparte by – = Duke One = –/Flickr