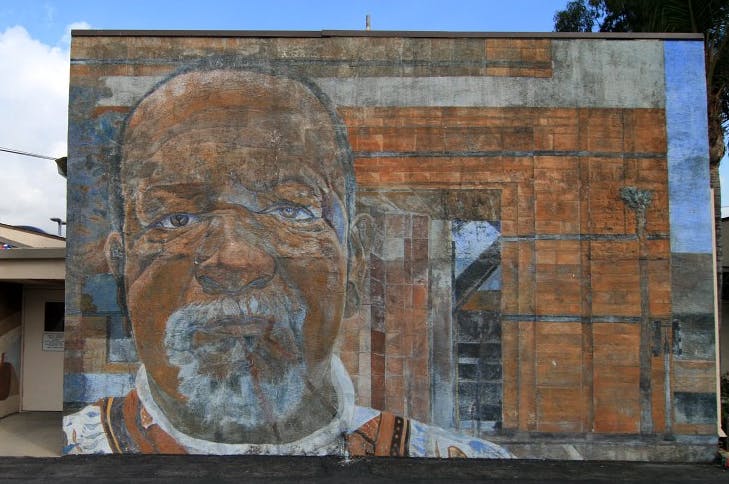

When Cecil Fergerson started his custodial job in 1948 at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, he envisioned far more for himself than a mop and broom. Cleaning up around the museum, Fergerson took an interest in the artwork he swept by every day.

He worked his way up through different jobs around the museum and became curator assistant at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. There he chartered the Black Arts Council advocating for the inclusion of African-American art. Fergerson went on to become the first black curator in the LACMA system in 1969—it took suing his employer for discrimination.

Fergerson had tested for the position and received a perfect score, but the museum refused to promote him. The court ruled in his favor and Fergerson became known around the world for his social justice advocacy.

Fergerson’s legacy lives on today as black artists are still struggling to make a name for themselves in the art world. His son, Kinte K. Fergerson, carries on his battle. Although not an artist himself, Kinte spent a lot of time in the black art scene of L.A. too, and he’s says it’s rough out there.

“A lot of institutions will turn down art from novel, black artists,” Kinte tells the Daily Dot.

Kinte has dedicated himself to promoting the work of black artists, with modern tools—from a publicly broadcast television segment to a podcast.

He started a Facebook group five years ago to connect black artists in L.A. That group, Black Artists Connected, has more than 100,000 members from around the world.

“We needed to have a group where black artists could come and share their work and ideas,” Kinte says.

He admits he didn’t pay much attention to the group for a number of years as it slowly grew. It wasn’t until a few months ago that the Facebook page started gaining traction as traffic to the group’s page increased dramatically, and thousands joined daily. Kinte had to assign several administrators to manage the overwhelming following—including artists who showcased their work. Page leader Lauren Richardson says the group’s newfound virality is an organic result of exceptional work and fans sharing.

“We did our work administratively, but it’s the artists that blew up the page,” Richardson says.

Richardson joined the page only a few months ago but has still had the opportunity to watch it grow. She compares it to a curated black art gallery, only online.

“We are creating our own virtual black experience,” Richardson says.

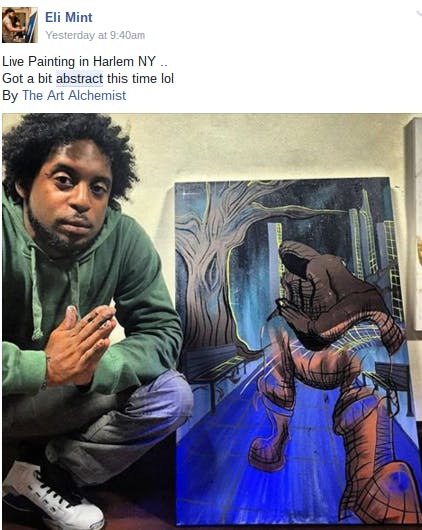

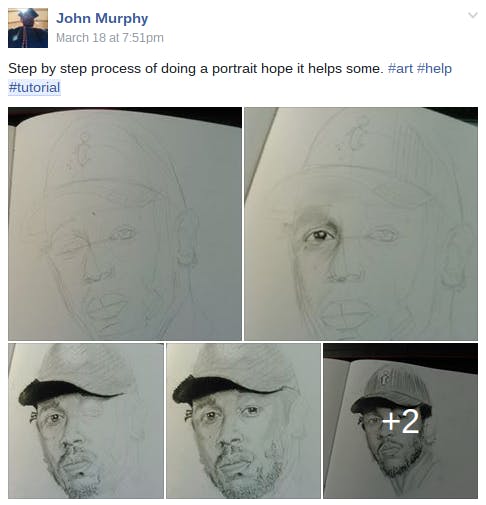

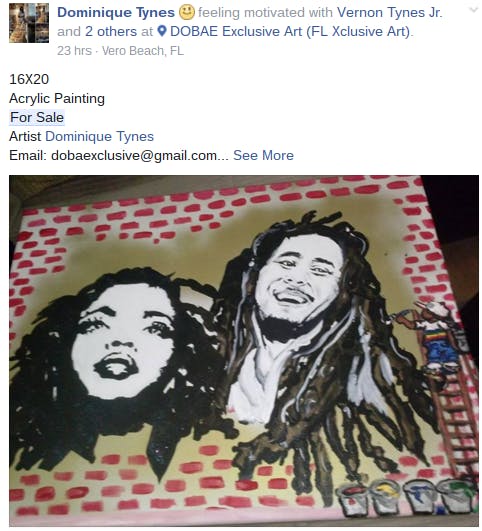

The formalized editorial schedule helps keep users coming back: There’s Medium Mondays, where artists share favorite materials used to produce their work. There’s Tutorial Tuesdays, where they can post videos of themselves creating, one step at a time.

Wednesdays are a free-for-all, and then it’s Thirsty Thursdays. That’s when administrators ask artists to share their social media usernames to increase their following on other platforms like Instagram and Twitter. On Feature Fridays, page admins showcase one artist with an interview and their best work.

Aside from the social networking aspect of the group, it also gives the artists access to an audience that values African-American art. According to Artsy, “works by 19th- and 20th-century African-American artists” remain “undervalued by the art market relative to those by white artists of equal standing.”

As such, the black community remains underrepresented across mainstream art galleries—to say nothing of mainstream retailers. A cursory scan across the online sales portals of stores like Target shows little-to-no diversity across painting subjects.

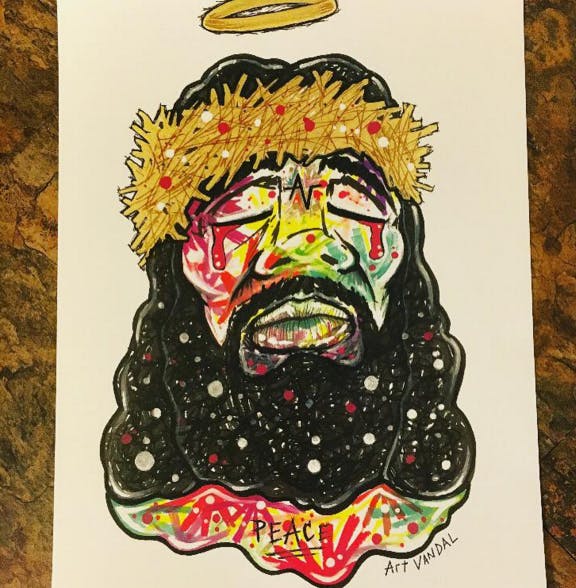

More urgently, Black Artists Connected also functions as a bazaar for a range of artists. It gives them critical access to a captive, receptive audience and a chance to cultivate a sizable fanbase.

“It’s art by us, for us.” BAC follower Charlysia Washington says.

For her, all it took to be hooked was a Facebook share that wormed its way into her feed.

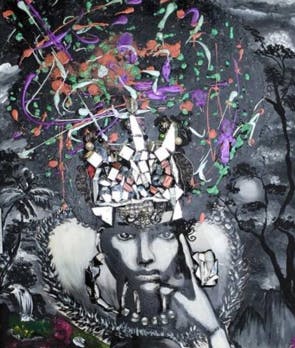

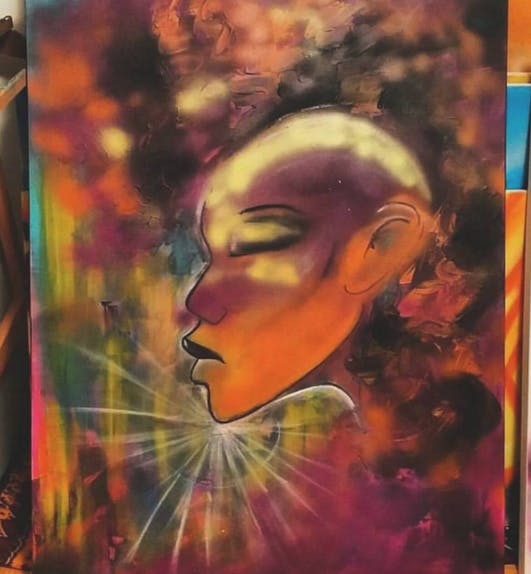

Kofi Frempong, a Canadian painter originally from Ghana, joined the Facebook group two months ago after a friend invited him to join. His latest work focuses on the complex beauty of black women. Frempong says he strives to deconstruct Western ideals of beauty.

“I see how women are portrayed in the media and my art is an expression of a counter to that. I like to believe that I paint black women in strong, powerful, beautiful roles,” Frempong says.

Initially reluctant to share his work with the group, Frempong was inspired after seeing artists receive so much support.

“I was blown away by the artwork I saw and I noticed the amount of love the artists were getting,” Frempong says.

After he finally posted one of his own paintings, it immediately sold. He now posts to the page almost every day. Living in Toronto, Canada, Frempong is grateful for the platform the group has provided for black artists like himself around the world.

He also says the art scene has a lot of catching up to do when it comes to showcasing and valuing the work created by black minds.

“The art scene right now doesn’t really appreciate our form of art or black artists the way it needs to. A lot of it is informed by a Eurocentric perspective,” Frempong says.

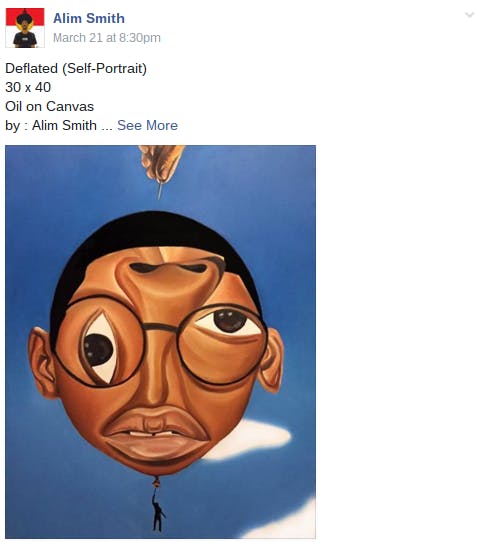

Brian Sholis, curator at the Cincinnati Art Museum, says there’s always been a historical oversight of African-American artists.

“Art museums over the past 10 to 15 years have been trying to address the failure to notice African-American artists,” Sholis says.

His museum brought on the exhibition “30 Americans” in March. It showcases the work of noted black artists over the past three decades. Sholis also says the lack of black curators plays a big role in the oversight of black artists. He admits curatorial staffs lacking diversity have blind spots.

“It’s a pipeline problem. … The numbers that make it up the ranks get smaller and smaller the higher up you go,” Sholis says.

He compares the institutional problem to industries like Hollywood. It’s hard to excel in opportunities that simply aren’t there.

“It’s not incumbent on the black artist to do anything other than continue making good and compelling art. It’s up to the rest of us in positions of power to support them, not on a tokenism basis with one exhibition, but in a consistent part of our vision for what an inclusive institution can be,” Sholis says.

Although the work of black artists is slowly making progress in the museum world, the digital world is speeding things up. Decades of work from black artists in the civil rights era are featured on Google’s Cultural Institute, the search engine’s virtual museum. The collection includes more than 4,000 archived paintings, drawings, sculptures, textiles, and photography projects portraying black life throughout history. Google linked out to the collection on its homepage during Black History Month.

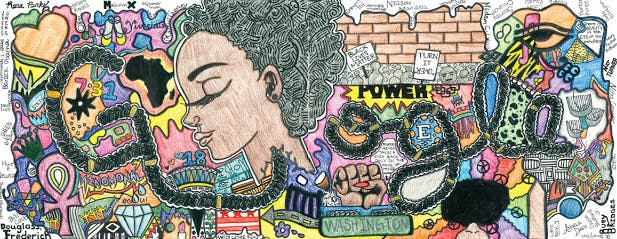

Google also featured the work of a black artist on its homepage in March as a part of its national Doodle 4 Google contest. Only a high school sophomore, Akilah Johnson used what she calls her definition of black heritage to spell the word Google. She beat out students from all around the country with her box-braid, Black Lives Matter mural.

Although black artists are slowly gaining national recognition, Richardson says they cannot wait on the art world to respect or include them.

“We want an Oscar, we want an Academy Award, we want an Emmy. But if we would take the time and create our own accolades we would learn that ours are equally valuable because we are equally awesome,” Richardson says.

The page has encountered mild dissent because it exclusively promotes black artists. Richardson and Kinte both say it’s crucial to have a space dedicated to only black artists in order to work together against issues that are unique to them.

“We are underrepresented in the art world, we don’t get a platform where we are seen all the time or even get respect as artists.” Richardson says.

But overall leaders of BAC say they aren’t letting people who don’t understand the need to support black artists distract them from their main goal—building a global network.

The group is planning a national expo for October in Atlanta. Artists will be able to sell their work, enjoy entertainment, and network. Kinte K. Fergerson says there is also a documentary in the works that will feature artists from the Facebook group.

For his part, Frempong looks forward to the day where black art is regarded as classic—and not second class.

“It will become its own platform where it’s just as respected and not regarded as alternative art,” Frempong says.

Cecil Fergerson, that trailblazer of a man who went from janitor to curator, would certainly agree.

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled Brian Sholis’s surname.

Photo via Frank Morrison/Facebook