By Rezwan

Facing threats, intimidation, and the fact that several of their colleagues have been assassinated, many secular bloggers in Bangladesh have stopped writing. Some have gone into hiding. They fear jail and possible death at the hands of the mobs that killed fellow bloggers. So it’s no surprise a number of them have left the country and are seeking safe refuge elsewhere.

They became seriously endangered in 2013, when a group of conservative Muslim clerics accused 84 people of “atheism” and writing against Islam, submitting a list of their names to a special government committee. Ali Riaz, a politics and government professor at Illinois State University, explains that there is a widely held but mistaken perception in Bangladeshi society that atheists are “anti-religious,” and there’s little room for informed debate on such issues.

How have bloggers become such a critical target for religious political groups? In an op-ed for the Dhaka Daily Star, Adnan R. Amin describes the contentious gap in historical reckoning that bloggers have come to fill:

Today, the very mention of the words [blogger] conjures notions of atheism, virulent anti-religious sentiments, religious propaganda and hate speech. It evokes emotions ranging from discomfort to anxiety to outrage. Yet, at least half our population does not know what a blog is, what it represents and what it can do. […]

Typically dominant Bangladeshi blog narratives either frame present politics in terms of the [Bangladesh Liberation War] of 1971, or link it to the global schism over Islamist ambitions and terrorism. Let us note that these narratives are not shaped by the technology of blogging, but by unresolved issues that keep Bangladesh from historic closure. The moral and ideological fractures surfacing in our blogosphere are rooted in the history and politics of Islam in Bengal, directed by the spirit of 1971 and lately, viewed through a post-9/11 lens. All of this is what makes blogging so contentious in Bangladesh.

Despite the fact that the country’s constitution guarantees freedom of speech, the threatened writers receive little support from the government. Some say the government is thereby endorsing religious politics and are soft on those who use religion for politics. Even the national Chief of Police, AKM Shahidul Hoque, warned that free-thinkers and bloggers should not cross the limit of tolerance while expressing their views on religion.

“With law enforcement crippled and the government unwilling to push back on fundamentalists too hard, the bloggers have been left to protect one another,” New York TImes Magazine reporter Joshua Hammond wrote in December. As the situation worsened over the course of 2015, more and more bloggers have opted to leave the country and seek exile.

Among them is blogger and online activist Mahmudul Haque Munshi. In a recent post on his blog Swapnokothok (Dreamweaver), he described his experience. Global Voices worked with Mahmudul to translate the following segments of his text, edited for clarity and brevity.

People leave their home country for a foreign destination for lots of reasons. Some go to study. Some relocate for a job or to start new ventures. Some travel abroad to be close to their loved ones and some simply to have a better life. For me, none of those reasons applied. I had to leave my country just to be able to live another day.

I never thought that I would leave my country. Where would I go where the beautiful earth-sky-water and air of my homeland is not present? I had a dream. A dream of a bright future. Of a healthy and beautiful country. I tried to help others a lot. Whenever disaster struck—during floods, when houses were damaged in cyclones, or if people were in peril after landslide—I would run there to volunteer in relief and rescue efforts. My family is not rich, so instead of donations I tried to volunteer my time and service. I believe in one thing: If we try to do something from our own reality, our own position, the society is bound to change. The country is bound to progress with such citizens.

My strength was my writing. I tried to achieve a lot with it, and it really was able to stir some commotion which I never thought would be possible. I used to read a lot. In our home there was a private collection of about five thousand books. I would use these resources in my writings in various blogs against those who oppose our liberation (fundamentalists) and I became enemy to a certain faction of bloggers. I used to read a lot of blogs too—different opinions. I read almost three thousand blog posts in a month. I realized how religion was being used to oppress our nation. How, citing religion, people proposed changing our language. How religion was used to commit one of the biggest genocides in history. After learning, all my disbelief in religion turned into anger.

I got involved in different kinds of activism related to blogging. I arranged blogger meetings, raised funds for relief and rescue of landslide victims in Chittagong, protested the arrest of blogger Dinmozur and Asif Mohiuddin, and protested against the Bangladesh cricket team’s tour to Pakistan, plus many more that I don’t recall. And my enemies started to increase. My mobile number was mentioned in my blog, so I got frequent calls threatening me. On other blogs, writers would say which ten bloggers would be killed if the current government falls. My name was on those lists.

But I didn’t let it bother me. Back then, killing bloggers for their writing was an unthinkable and laughable idea. But it became a reality on February 14, 2013, when my close friend, blogger Thaba Baba (Ahmed Razib Haider), was hacked to death in front of his home.

After that, murder threats against me increased. In the meantime, four bloggers I knew well were arrested by the government. One of them handed over proof of some of my anonymous writing promoting atheism to the detective branch of police. I don’t blame him, he was threatened and coerced to expose others. In the meantime, the list of 84 bloggers with blasphemous and atheist writings, which included my name, was handed over to the home ministry. Then I got frequent calls from the National Security Intelligence. They said they have proof and can arrest me anytime. While I was at the Shahbag protests, someone tried to light my clothes with gunpowder and fire, but luckily my friends put that fire out. I couldn’t post on Facebook without trouble—I would get calls from the NSI. They would tell me some of my points were right, but that I shouldn’t have written them online and should remove them. In the meantime, the lists grew and were being published in lesser-known newspapers. Fake lists, with new names, circulated. I know some people who created some of those fake lists to include their own names, just to become famous.

When Avijit Roy was killed, I was furious. Some of my friends told me we should retaliate and create an underground team. But I thought, who should we kill to stop this madness? We weren’t sure who was killing our brothers. During that time, blogger Farzana Kabir Khan Snigdha, in Germany, urged me to go abroad. I did not agree. I told her I would not seek asylum anywhere. I could go abroad for one or two months if things got really bad, but I would not leave my country forever.

When Washiqur Babu was killed, I cried because I could do nothing to keep him alive. After that it was Niloy Neel. The assailants dared to enter his room and kill him in front of others. I then talked with some acquaintances to prepare a kind of resistance by targeting those who were keeping an eye on us. We had two meetings about this. But then I saw that I was being followed everywhere. I became very afraid. I remembered Niloy said that they started following him two months before his death. I am not sure whether they found out our plan for resistance through some leakage. I don’t trust the police for the same reason.

By then, I was hiding in a neighbouring country. I got a letter from a reputed organization in Germany that I received the scholarship I applied for earlier. My family was happy, but also afraid, because I had to come back to Bangladesh to apply for the visa. What if something happened before then? My wife and I got the visa appointment twenty days later. I hid in my village home after coming back.

I have a guilty feeling. We fought, but then abandoned the fight, leaving the battlefield. But how is this war? How can you fight with shadows? To those who wanted me to die in vain, I would like to tell them: You will not win. I will live. I have to do a lot of things. I cannot die before achieving some of that.

We are bloggers. We were not supposed to be on the streets. We were supposed to write; we were to remind the society about its faults, its shortcomings, and give it a direction. We had to come to the streets and we will do the same again if needed. But we need to carry on with our main job, to write more. We have to keep in mind that our responsibility has grown more. I have to also write for my friends who were killed, and their dreams. If I did not pay heed to their thoughts or dreams earlier, I should also write about those now. Because our assailants want our keyboards and our pens to stop. They want us to cringe with fear and be silent. So now, it’s the time to write even more. Write our thoughts, and also our slain friends’ ones. Otherwise the darkness will win; religious fundamentalism and extremism will win.

Originally published at Global Voices. Republished under CC license and with author’s permission.

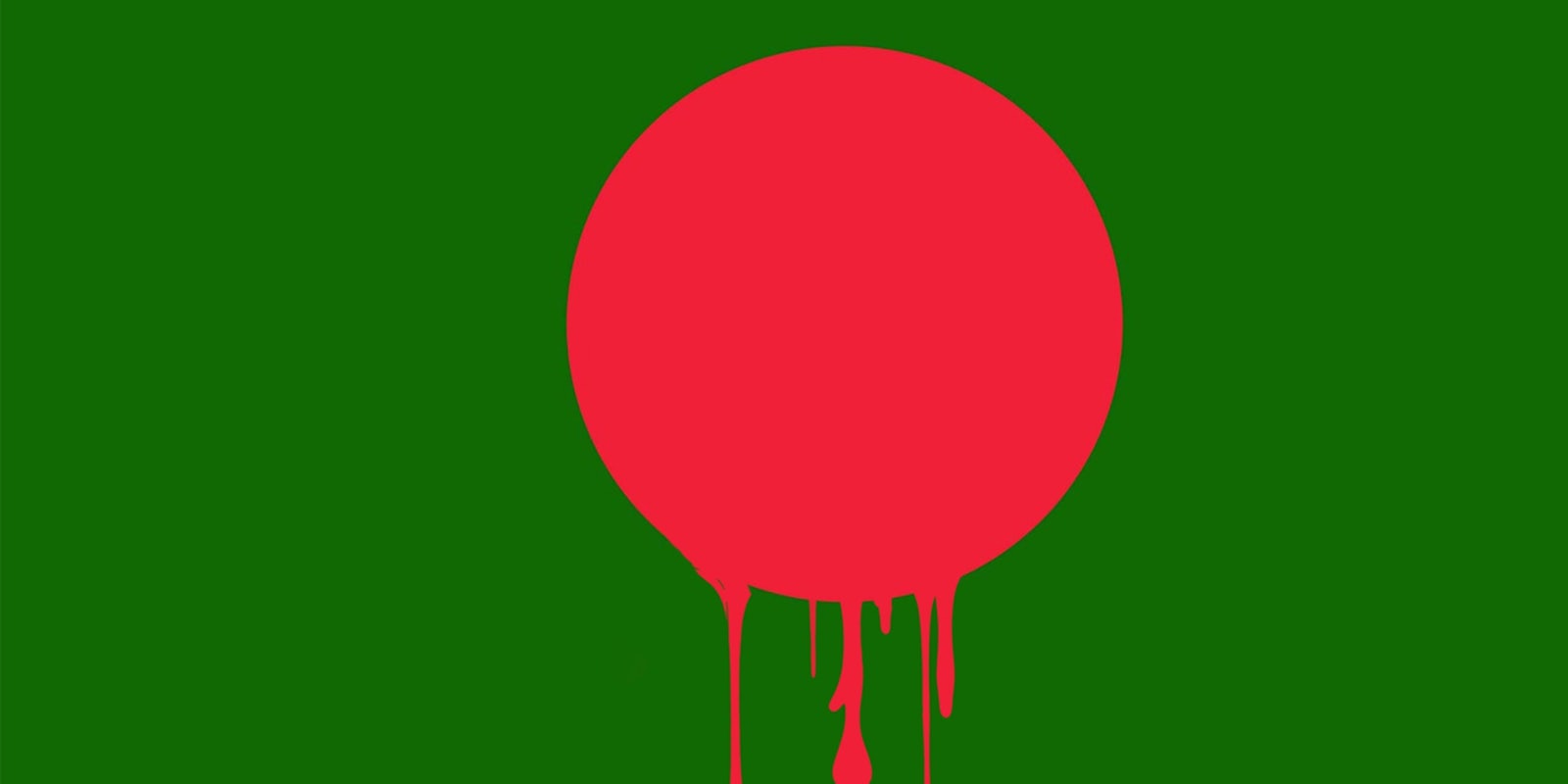

Illustration via Fernando Alfonso III