By the time I spotted my mother coming through customs at Logan International Airport, my daughter had too. “Mimi!” she shrieked, and hobbled off to be scooped up by her grandmother.

It was the toddler version of countless airport greetings, but it was amazing, since my 1-year-old daughter hadn’t seen my mother in person since she was 6 months old.

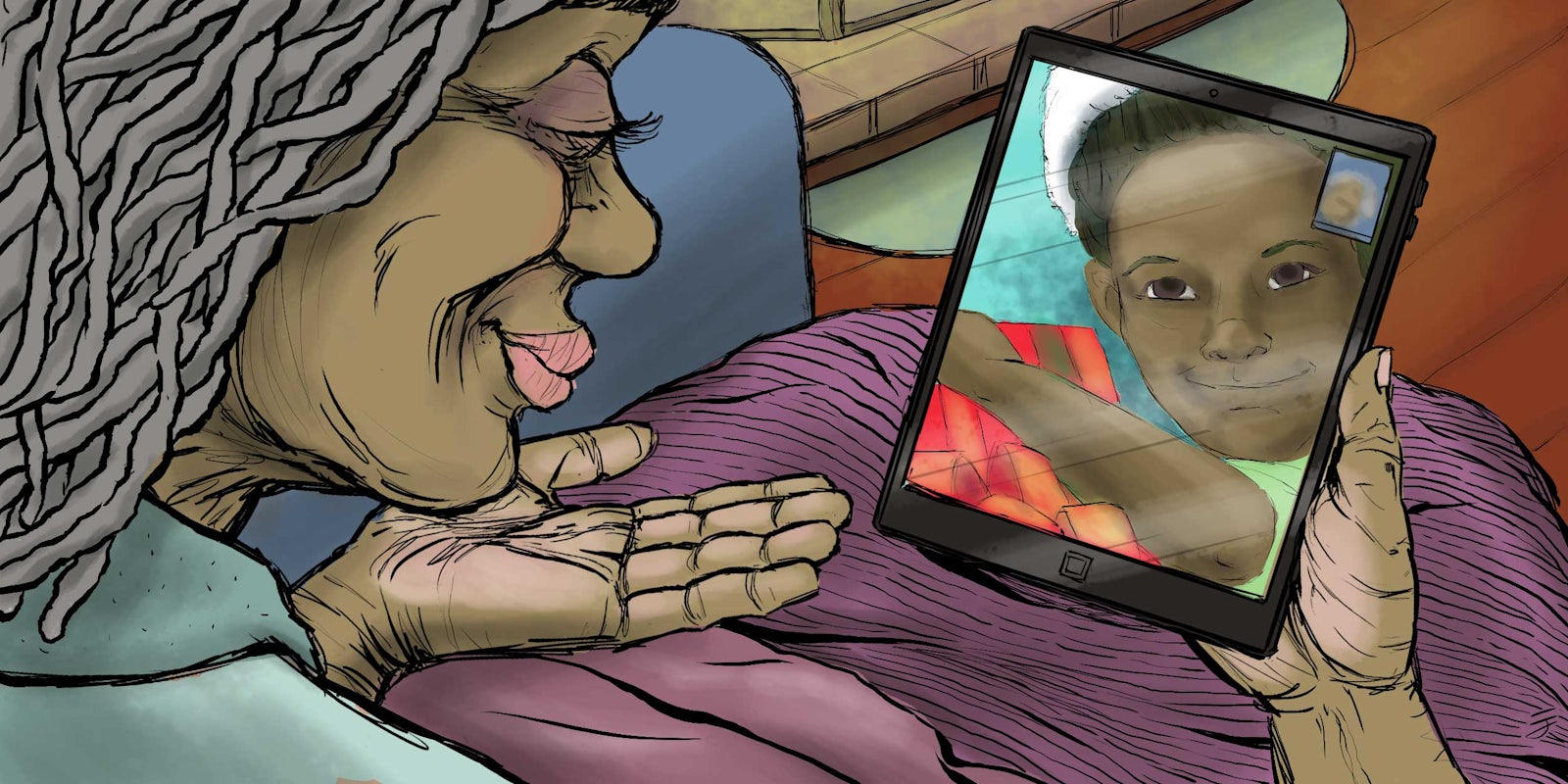

“She knows me,” my mom gushed, teary-eyed. She did indeed, thanks to the video-chatting technology that keeps our family connected.

Each day, my 18-month-old eats breakfast with her grandparents in Dubai, and dinner with her grandparents in Australia, all without leaving our home in the hills of New Hampshire. While family meals have always been a time to reconnect and recharge, share stories and laughs, in our house this ritual has taken on a distinctly 21st-century spin, with the help of FaceTime and Skype.

“Parents want to stay in touch with their parents, and to connect their kids with their parents in some way, and video chat is really the best way to do that right now,” said Morgan G. Ames, Ph. D., a researcher at the University of California, Irvine who has studied the role that video-chatting can play in families. In researching her paper, Making Love in the Network Closet: The Benefits and Work of Family Videochat, Ames observed how families use technology and interviewed people about their tech usage. She found that families that lived further from grandparents made a large effort to keep in touch through video calls between kids and grandparents.

“Video in particular really added a dimension that families said was so important,” Ames reported. “Family togetherness and sense of continuity between the generations was really important and something that many [parents] talked about growing up with, and it’s something that they wanted their kids to have as well, one way or another.”

With unprecedented geographic mobility across the globe, more kids are growing up without their grandparents around the corner, and more families are turning to tech to help foster intergenerational bonds.

In Marissa Hill-Dongre’s home in Minneapolis, Minnesota, FaceTime calls often happen at dinner, when her sons, ages 2 and 5, can connect with their grandmother, uncles, and cousins who live in Australia.

“It feels like we’re having a meal together,” Hill-Dongre said. Oftentimes, her in-laws will eat what her sons are eating or play music for the boys to listen to over dinner, sharing an experience across thousands of miles. “It makes it so that their grandparents aren’t strangers.”

Hill-Dongre says that video chatting has not only benefitted her sons but has also opened the door for an easier, more natural relationship between her and her mother-in-law.

“It’s hard to sit down and have a 20-minute phone conversation,” she said. “But if I can show her art work that the Kindergartener has done and she can listen to the boys sing, it’s more like being in the same place. The conversation happens more organically.”

Hill-Dongre’s family will be visiting Australia this winter, and she believes that her sons will have an easier adjustment because they regularly video chat with their Aussie family.

“My little one is reserved, so I think the FaceTime relationship will make it a quicker warm-up for him,” she said. “He’s seen this kitchen before, and knows these people. I’m hopeful that getting to see and talk to their grandparents and international family regularly will make them have some connection, so that we’re not starting at zero.”

Just like any visit from the grandparents, video calls can come with their own set of stressors. Time differences can make for tired babies, and busy children aren’t always willing to sit still and stay in front of a screen.

“I spend a lot of time translating between my sons and the family,” Hill-Dongre said. “It’s a little bit unnatural but it’s better than nothing.”

Grandparents who aren’t very savvy with computers and technical problems with the apps themselves add another layer of frustration.

However, the fact that so many families push through the problems shows how important video-chatting has become. But, as Ames notes, “the fact that parents still went through them once a week or sometimes even more was a testament that making the calls was incredibly important to them.”

Parents aren’t the only ones working at the relationships. Grandparents who once knew nothing about computers, tablets, and smartphones can become interested when they realize that the technology can be used to keep in touch with family.

“I was going to go to my grave without ever touching a computer,” said James Maley, 80, a resident of Brookdale Burr Ridge, a senior living community in Burr Ridge, Illinois. “Now it’s my friend. It’s a whole new world for me. I love it.”

Maley uses an iPad to keep in touch with his grandkids in Illinois, Wisconsin, and California. The grandkids range in age from toddlers to a college student.

“I’m much closer with them,” he said. “Well, I shouldn’t say closer, because I’ve loved them the whole time. I’m really involved in their lives, and this allows me to be even more so. For me, it’s a really good thing.”

It’s a sentiment that many grandparents can relate to.

“Thank God for Skype,” my mom said on a recent video chat as she watched my daughter stacking blocks. “I can’t imagine being away and not being able to see you guys.”

My daughter finished stacking her blocks, and turned toward the phone’s screen.

“Yay,” she said, clapping her hands.

“Yay,” said my mom in Dubai, clapping her hands as well.

The active interaction between children and the people who love them is one of the undeniable benefits of video-chatting. Especially for young children, who rely heavily on non-verbal cues, video chat allows a level of interaction that phone calls simply can’t match.

“Video is so much more evocative,” Ames said.

In early October, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released changes to its recommendations for kids and screen time, acknowledging that we now live in a world “where ‘screen time’ is becoming simply ‘time.’” It was a significant departure for the organization; previously, the AAP recommended that kids younger than 2 get no screen time at all, and that older children have strictly limited access. However, the new recommendations emphasize the quality of the screen time, rather than just the quantity.

In general, the more interactive a technology is, the more educational value it holds. In a news release, the AAP specifically mentioned toddlers video-chatting with family members as a positive use of technology.

“Things like video chat can actually benefit kids socially,” Ames said. “I’m heartened by [the AAP’s] change of stance. It vindicates a lot of what I’ve seen with the parents that I’ve studied and in my own life.”

For my family, the benefit of using screen time to keep in touch with the grandparents is undeniable. My daughter had her first video chat at just hours old, squirming and blinking in the hospital bassinette.

“She’s perfect,” my father-in-law whispered in Australia.

When she was younger, our talks were for the benefit of the grandparents, who could watch her grow and change, even if they couldn’t be here in person. Now, at just 18 months, she asks to make the calls.

“Papa?” she says, handing me my phone. “Mimi?”

“Growing up, I had friends who had grandparents who lived far away and they were basically very loving strangers,” Hill-Dongre said.

For my daughter, Hill-Dongre’s children and the millions of other families who keep in touch with video chat, the grandparents may be behind the screen, but they certainly are not strangers.

Illustration by J. Longo