Reactions to the mass shooting in a Lafayette, Louisiana, movie theater that claimed three lives and injured nine others last week have been all over the place.

There was widespread showing of emotional support—many celebrities took to Twitter to share their horror, including Amy Schumer, whose first feature film Trainwreck was showing in the theater during the event. “My heart is broken and all my thoughts and prayers are with everyone in Louisiana,” Schumer posted with the film’s executive producer Judd Apatow echoing her sentiment.

https://twitter.com/amyschumer/status/624419088924741632

Singer Sam Smith, author John Green, and retired athlete Barry Bonds also extended their sympathies to the victims and their families.

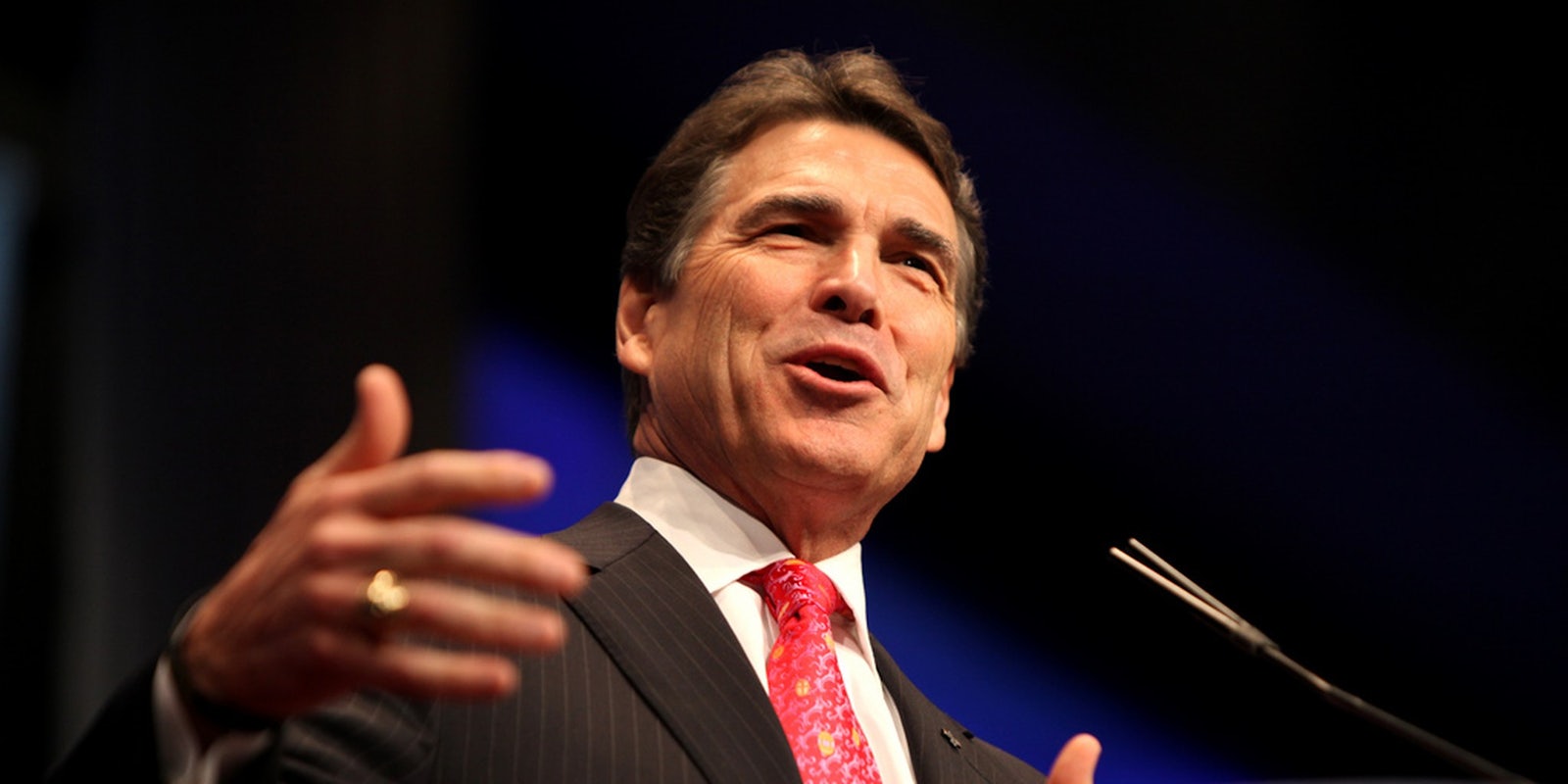

As might be expected during a surprisingly competitive presidential race, others used the Louisiana shooting as a political opportunity to espouse one of many popular myths about what causes such mass shootings. Former Texas Gov. Rick Perry, who ranks 11th in the crowded GOP nomination race, blamed Friday’s shooting not on the prevalence of guns but on their supposed absence in public spaces.

“I will suggest to you that these concepts of gun-free zones are a bad idea,” Perry told CNN. “I believe that, with all my heart, that if you have the citizens who are well trained… that we can stop that kind of activity, or stop it before there’s as many people that are impacted as what we saw in Lafayette.”

The “gun-free zone” as an easy target for mass shooters is a popular myth among gun advocates. As National Rifle Association President Wayne LaPierre famously said, “the only thing that can stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” Such advocates imagine John McClain-esque vigilantes shoring up their everyman courage to prevent such disasters by putting down the attacker or—through their increased presence in malls, schools, or movie theaters—deter attackers overall.

Perry’s argument relies on a poetic vision of these attacks because such thinking lacks the data to stand alone. Study after study has found that where there are more guns, there are more likely to be gun crimes. The American Journal of Medicine analyzed the crime and gun ownership rates of 27 developed countries and found a strong correlation between the number of guns and the number of homicides. In a dense and thorough review of the academic literature on gun crimes, the Harvard Injury Control Research Center found overwhelmingly that states with higher rates of gun ownership experienced higher rates of homicide overall, but especially in fatal gun crimes.

In fact, even the “good guy with a gun” is an exceedingly rare phenomenon, with less than 3,000 defensive uses of a firearm in 2013 compared to the tens of thousands of gun homicides in that same period.

This should be obvious, as much an assumption as “where there are more bears, there are more bear attacks.” But the legend fighting against such a self-evident point has proven a reliable meme among gun advocates and lobbying agencies. The genesis of the argument put forth by Rick Perry likely comes from economist John Lott who, in the 1990s, claimed to have found a correlation between a reduction in crime rates and when states passed laws allowing concealed carry of handguns.

In his controversial books More Guns, Less Crimes and The Bias Against Guns, Lott studied the crime rate of every county in the U.S. in an effort to find any trend between gun laws and gun crimes. Lott claimed that, when a state passed a concealed carry law allowing private citizens to carry handguns, the crime rate significantly decreased and the defensive use of firearms rose prominently.

“When state concealed-handgun laws went into effect in a county,” writes Lott, “murders fell by about 8 percent, rapes fell by 5 percent, and aggravated assaults fell by 7 percent.”

This would appear to be a confirmation of the arguments put forth by Perry and other Republicans. After the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, in which a 21-year-old used a semi-automatic rifle to kill 26 people (including 20 school-aged children), Rep. Louie Gohmert (R-Texas) cited Lott’s research specifically to claim that “every time… conceal-carry [gun laws] have been allowed, the crime rate has gone down.” This suggests an armed school official could have prevented the attack.

Lott himself backed up the case against gun-free zones in 2011, writing in USA Today: “Would you feel safer with a sign on your house saying ‘this house is a gun-free zone’? But if you wouldn’t put these signs on your home, why put them elsewhere?” Echoing Perry’s statements, Lott writes: “Killers go where victims can’t defend themselves.”

However, many of Lott’s findings have been challenged by numerous review boards, including a comprehensive 2004 report that called into question much of the methodology Lott has used to connect concealed-carry laws with decreased crime rates. In addition, Lott’s concluding point is the ultimate myth about gun-free zones. Such advocates speak as if this is simply a problem of arming citizens—not disarming the hatred of women that characterized his thinking. Would arming public spaces have stopped Elliot Rodger?

In fact gun restrictions on a public space are rarely a factor where mass shooters decide to murder, according to a Mother Jones analysis of 62 mass shootings since 1982. Most shooters choose their targets based on other distinctions; many were workplace shootings, while most school shootings were perpetrated by previous alumni or students.

The difficulty in understanding mass shootings is highlighted by our inefficiency in stopping them.

More evidence to that effect is the number of shootings in public spaces there are guaranteed to be guns and armed guards, as shootings at military bases have seen an increase in recent years. After a recent shooting in a Chattanooga, Tennessee, naval recruitment center, the Pentagon specifically requested that armed civilians not attempt to guard such offices, citing the likelihood of “unintended security risks.”

The difficulty in understanding mass shootings is highlighted by our inefficiency in stopping them. We have no certain proof of why John Houser decided to shoot up the attendees of the 7:10pm showing of a romantic comedy, despite some public ramblings and claims of mental illness. But what is not helpful is the baseless reliance upon debunked notions about vigilante justice. America’s mass shootings problem is not helped by useless solutions—and in the case of fighting for more gun ownership, it make the problem even worse.

Gillian Branstetter is a social commentator with a focus on the intersection of technology, security, and politics. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, Business Insider, Salon, the Week, and xoJane. She attended Pennsylvania State University. Follow her on Twitter @GillBranstetter.

Photo via Gage Skidmore/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)