How much can guilt or innocence be shaped by outside forces? And just how many times can it happen to one man?

In the wake of 2015’s acclaimed true-crime bookends—HBO’s The Jinx and podcast Serial—the genre is imminently binge-worthy and Netflix is making its case with Making a Murderer.

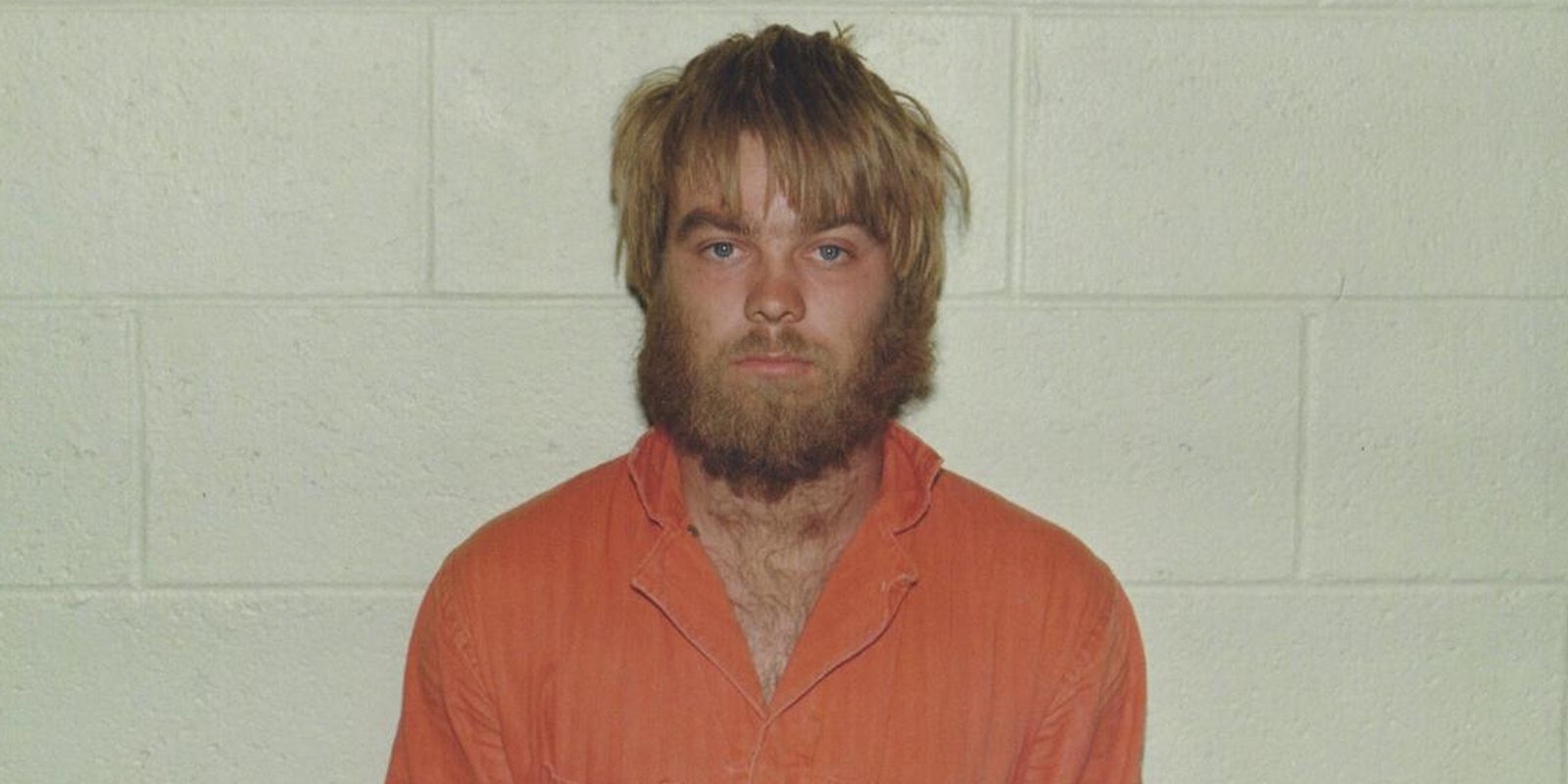

The 10-part series from filmmakers Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi, who spent the last decade working on it, begins when a Wisconsin man named Steven Avery is released from prison in 2003, after DNA evidence cleared him of a sexual assault charge stemming from a 1985 case.

After spending 18 years in jail, Avery becomes a figurehead for justice-system reform, but in the first episode, we’re also shown the twisted family tree of Manitowoc County, where Avery’s family roots run deep. Avery had previously spent time in jail for burglary and animal cruelty.

His cousin is married to the sheriff, and his uncle is a cop, too. Small-town politics appear to play a big part in Avery’s arrest and eventual conviction for the 1985 rape of Penny Beerntsen, but Demos and Ricciardi zoom out and illustrate the larger miscommunications and apparent corruption among law enforcement, unraveling a more gnarled timeline.

The question subtly posed in the title: Is it possible to “make” Avery into a murderer? Much like The Jinx, which explores the bizarre life and crimes of Robert Durst, there’s an unbelievable twist.

In 2005, a woman named Teresa Halbach goes missing in Manitowoc County, and once again Avery is a suspect. Interviews with family members, acquaintances, and lawyers, as well as archival testimony and recorded phone calls of Avery, piece together what appears to be a miscarriage of justice by law enforcement against an economically disadvantaged man. “Poor people lose all the time,” Avery explains in one phone call to family after the 2005 accusation.

The filmmakers also pull at threads on Avery’s side, but there are so many “Wait… what?” moments involving law enforcement and outside forces that it’s hard to keep an unbiased sketch in focus, especially after witnessing the chilling interrogation of a 16-year-old boy in the case of Halbach. They create a feeling of unease that never quite lets up, amplified by the bleak socioeconomic conditions in which the Averys exist—a theme the filmmakers return to quite a few times.

As with Serial and The Jinx, these pieces of “entertainment” can have real-life consequences on subjects. Making a Murderer plays outs better if you don’t get obsessive and Google details about the case, but it succeeds in putting you in that state of mind.

Photo via Netflix