A major surveillance software firm helped Morocco’s intelligence agency target journalists critical of the government, according to leaked company documents.

On Sunday, Italy-based software firm Hacking Team suffered a major security breach that resulted in the release of some 400GB of files stolen from the company’s servers.

Documents included in the release show that Hacking Team billed the Moroccan government over 3 million euros ($3.4 million) for access to the firm’s surveillance software, Remote Control System (RCS). According to Hacking Team’s records, the purchase was made on behalf of the Directorate for the Surveillance of the Territory (DST), Morocco’s premier intelligence service.

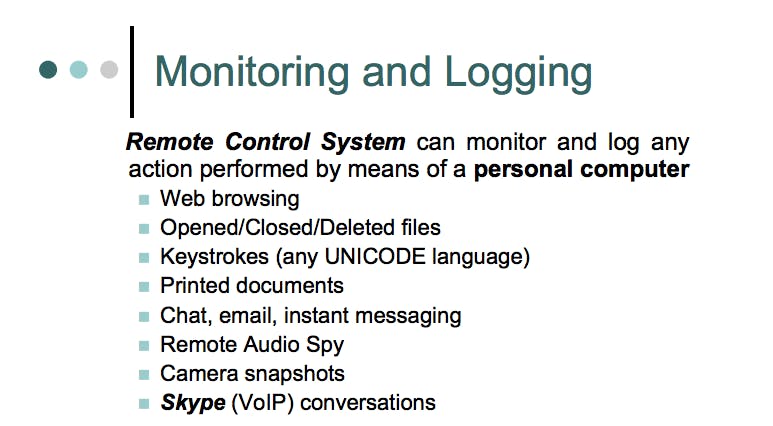

RCS, marketed as “the hacking suite for governmental interception,” is used by several dozen of the world’s intelligence and law enforcement agencies, including those in the United States, Hacking Team documents show.

Hacking Team describes RCS as a “stealth, spyware-based system for attacking, infecting and monitoring computers and smartphones.” According to the company, it provides “full intelligence on target users even for encrypted communications (Skype, PGP, secure Web mail, etc.)”

Provided with constant updates, Hacking Team claims its wiretapping tools remain invisible to antivirus, anti-spyware, and anti-keylogging software. According to leaked documents, RCS has been deployed in multiple countries known for the arbitrary detention of journalists and human-rights activists, such as Turkey and Sudan.

The use of Hacking Team’s software to target journalists in Morocco was first detected in August 2012 by security experts at Citizen Lab, a research center at the University of Toronto. Writers at Mamfakinch, a citizen-media project that began in the wake of the Arab Spring uprisings, received an infected email file, disguised as a Microsoft Word document containing details about a political scandal. Two weeks before, the writers had been awarded by Google and Global Voices for work critical of the Moroccan government, drawing suspicion that the infected email was connected to Mamfakinch’s reporting.

“There is no evidence in those files we are doing anything illegal…”

Morocco’s few journalists not employed by a government-owned corporation face frequent harassment and imprisonment for investigating state corruption and criminality. While the country’s monarch, King Mohammed VI, was largely praised during the Arab Spring for promising to pursue progressive reforms—several of which were enacted under a constitutional referendum in July 2011—many oppressive laws remain in effect and are used to silence voices of dissent.

Mustapha El Hasnaoui, a journalist at Assabil magazine, was sentenced to three years in prison under Morocco’s anti-terrorism law in July 2013 after attempting to visit Syrian refugee camps. During his trial, Hasnaoui claimed that he never read the confession he was forced to sign, and that his arrest was retaliation for refusing to supply Morocco’s intelligence services with information.

Another case that raised alarms for human-rights organizations is that of Ali Anouzla, a prominent journalist and co-founder of the now-defunct Moroccan publication Lakome. In September 2013, police arrested Anouzla at his home in Rabat and seized the computer hard drives from his company’s office. Lakome’s website was shut down a month later and subsequently blocked by Morocco’s Internet service providers.

The arrest of Anouzla was widely viewed as retribution for a Lakome exposé that drew international attention and sparked unprecedented political unrest in the country. In what became known as the Daniel-Gate scandal, the Lokome article revealed that Mohammed VI had brokered a deal with King Juan Carlos of Spain to release 48 Spanish prisoners held in Morocco—among them, a pedophile named Daniel Galván Viña who was sentenced to 30 years in prison for the rape of 11 Moroccan children. The youngest of Viña’s victims was 2 years old.

Documents leaked on Sunday reveal that Morocco’s intelligence agency had access to RCS for up to two years before, and two years after, the Mamfakinch journalists were targeted in 2012. Following reports that tied the eavesdropping virus to Hacking Team’s software, a company spokesperson told Reporters Without Borders (RWB), “We take precautions to assure our software is not misused and we investigate cases suggesting may have been.”

Hacking Team was subsequently labeled by RWB as a “digital mercenary” and one of five “Corporate Enemies of the Internet,” whose products aid repressive regimes in violating human rights and freedom of information.

In an interview on Tuesday, Hacking Team spokesman Eric Rabe downplayed the damage done to his company by the release of its private communications, client lists, and other private documents.

“We must make changes in the system to make sure this [detection] doesn’t happen,” Rabe told ZDNet. “It has impacted the ability [of law enforcement] to follow suspects of crime.” The real damage, he insisted, was done to the company’s product, the source code of which has been leaked to the public.

“There is no evidence in those files we are doing anything illegal, and I would argue, ‘unethical’,” he added. “We are trying to further lawful activity, and that is what we do.”

Hacking Team has reportedly contacted its government-clients by email and requested that they discontinue use of its intrusion and surveillance tools.

Photo by hackNY.org/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed