My favorite non-fiction genre, one the internet excels at, is “intelligent shit explained casually.” It’s a Sartre summary by Philosophy Bro, or Bloomberg’s Matt Levine talking electronic stock trades, or Drunk History on cosmic background radiation. You find a lot of this in the Explain Like I’m Five subreddit. These aren’t just the lucid explainers of a news article. While they’re teaching you, they’re also making sly asides. They’re swearing a little. They’re respecting your intelligence and filling you in like physics or economics is a bit of gossip. But they’re also leaving room for some crucial strong emotion that doesn’t make its way into a dry explainer: “FUCKING BERNINI THO.” “It’s like magic! TA-DA, BITCHES!” “You can’t really base the financial system of the future on computers rather than humans.”

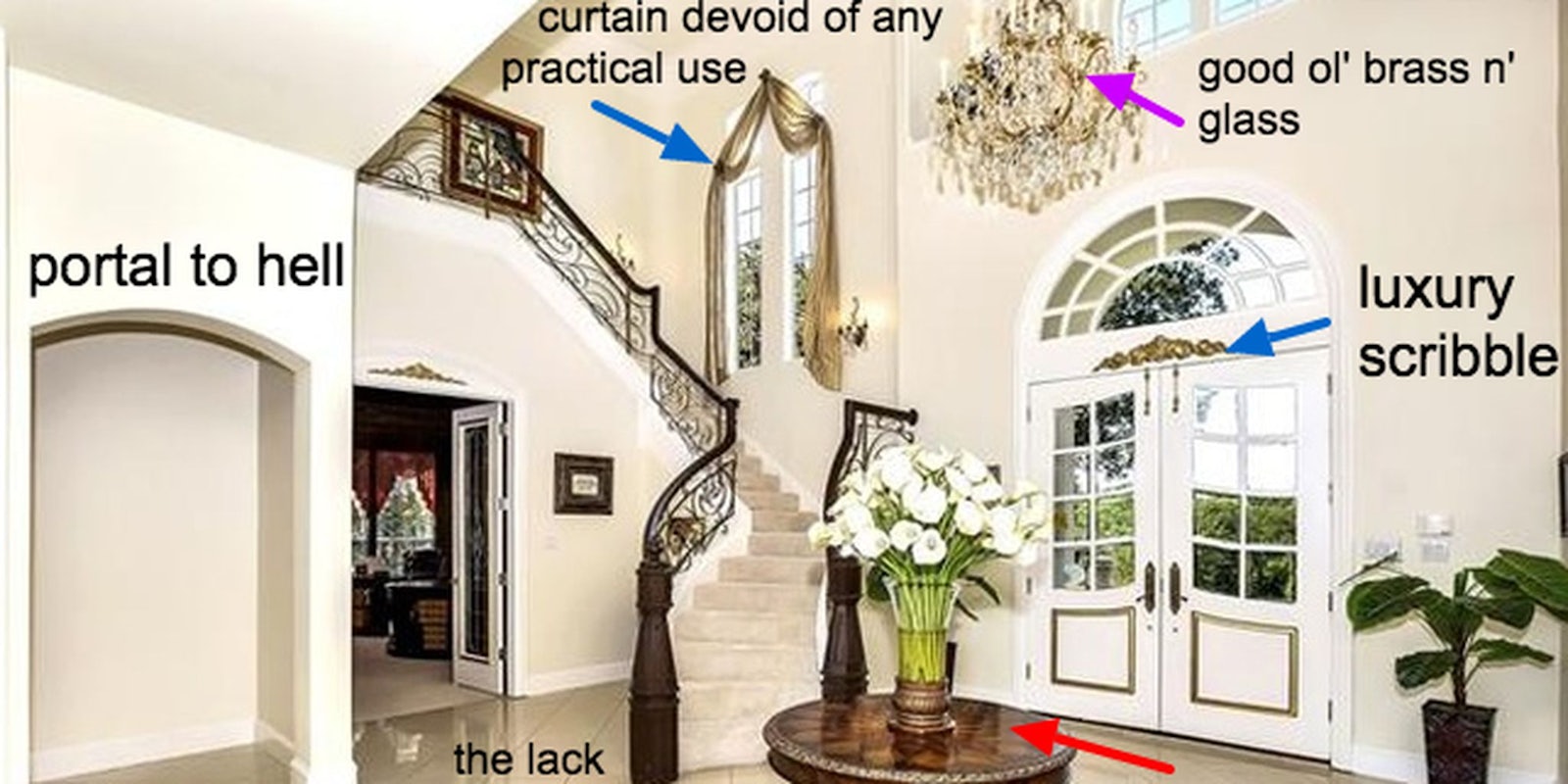

So I’m proud to show you McMansion Hell. Unless you already know about it and you’ve skipped ahead to the interview. If not, McMansion Hell is a Tumblr by Kate Wagner, who critiques the big shitty houses built from the Reagan housing boom to the present. (“McMansion” generally means a mansion-size house put together with shoddy craftsmanship, without an architect, and therefore hideous and gaudy.)

Wagner roasts one house at a time, pointing out specific architectural flaws but also having a go at the decor. She doesn’t just nitpick; she lays out some architectural principles and the history behind the phenomenon. In between these roasts, Wagner is building “McMansions 101,” a series of higher-level lessons on the common threads between McMansions (e.g., mismatched windows and massive roofs). New readers should start here. Knowing the theory makes the one-off posts way more fun, and none of it feels like eating your vegetables. Everything here is dessert.

Wagner didn’t invent McMansion critique; she recommends Virginia McAlester’s 1984 book A Field Guide to American Houses and essays like Thomas Frank’s “Let Them Eat McMansions!” and Stan Cox’s “Big Houses Are Not Green.” But Wagner brings the style and eager obsession of a top-shelf gossip blogger. She writes things like “so many oaks died for this” and “I bet you don’t even have a double dishwasher, you lowlife piece of trash.” She answers reader questions playfully. She’s not a cool teacher, she’s the wise T.A. Which is why she’s getting so popular.

Over just five weeks, the blog has earned over fifteen thousand Tumblr followers, a flurry of write-ups, and interviews in Paper Magazine (where Wagner first revealed her identity), Business Insider (very interested in pricing), and Realtor.com (even they are on her side!). Wagner is fielding columnist opportunities and a possible book deal. I called her up to talk about the blog’s success, its origin, and the vast gulf between McMansions and modernist architecture.

First off, congratulations on how much this blog is blowing up. It looks like it’s unusually fast.

When I wrote the first post that went viral—What Makes a McMansion Bad Architecture—before that post, this blog was for my fifteen followers. Some huge Tumblr celebrity, SlimeTony, shared it. After that happened, it really took off. It’s only a month old and all this crazy stuff has been happening. Suddenly it got linked on Boing Boing, then all these other things.

You’ve branched out onto Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. Were you on social media a lot before this blog?

It was something I started doing after. A friend of mine was like, “You need to snatch up those handles or you’re going to get impostors.” I used to be really big into Reddit for years. After the wave of the right-wing people started coming into Reddit and it started to get a lot more hostile, I had to say goodbye.

Just kind of abandoned it after that?

Yeah, I had to. You can tailor your Reddit, mine’s full of botany and architecture and stuff. [But] the crazy people were starting to seep into even reasonable subreddits. It became so toxic, mostly about women and minorities. I try to be as apolitical as possible in the blog, but honestly I just can’t stand people being ridiculed for things that they just can’t change.

One of my posts got shared [on Reddit] and one of the first comments was, “Well someone thinks they went to art school.” I was just like, “Dude, fuck this.” I can’t be bothered with that. It’s such an anti-intellectual attitude. You should always try to empower people who learn about the world around them. Anybody who says not to do such a thing is just wrong.

Where do you draw most of your architectural knowledge from? Are you self-taught?

I’m in a grad program for acoustics so I’ve been around the architecture circles; I’m at Johns Hopkins. I’ve been reading and writing about architecture since I was in high school, [but] this is the first time any of that has been public.

I’m a writer first. I moonlight as an interior designer for friends and family, I get paid for that sometimes. I’m not an architect, but now I get paid to write about architecture, so it’s pretty cool. Some people have reached out to me about doing weekly syndicated articles, and I’ve been invited to write a book. I’ve also been invited to talk at TEDx Mid-Atlantic. My Patreon account is doing really well. I’m starting to think about further places to take things.

McMansion Hell started as a joke between me and some friends, where I would take houses off of real estate listings and just talk about how stupid and ugly they were. This has been a subject of eternal fascination of mine since my early youth. I’ve always been fascinated by the sociology of housing and how economics and socioeconomics influence design trends. That’s sort of what I want to write my book about. The big ugly house didn’t just spring up out of nowhere. It has an emerging story that goes back a very long time, longer than most people realize.

Are you talking about suburbanization, or further back?

One main starting point was the car, of course, [and then] the Federal Highway Act. The other thing was that when modernism became more of an institution than an aesthetic, architects left the field of small-scale residential design. They wanted bigger public work, public buildings, and extremely wealthy clients.

That left an empty field for developers and marketers to move in and start with Levittown and all of the 1940s and ’50s. Building corporations. We think of builders as, like, the nice guy who built our house, but he’s part of a huge multi-national billion-dollar corporation with a head of marketing that builds these houses based off of trends. They were just like any other company.

In the 1980s what really accelerated this process is, we started to see a shift from housing and our homes being a place to have experiences, to being an object and an asset. Some of that is caused by mortgage speculation that began with the deregulation of savings and loans. In the early 1980s they signed a law that the government could issue adjustable rate mortgages. That enabled more and more people to buy houses. It also enabled more and more people to speculate on mortgage aspects. Because of this, suddenly house size from the 1980s through 2005 increased 35%, which is a huge number.

The ’80s were a cultural reaction to the severity and the energy crisis of the ’70s and the social crisis of the ’60s. This is a generation that’s like, “OK, we’ve been beating ourselves up for so long, we just really want to have fun and buy things.” To be fair, I understand why it happened that way. I’m only 22, but my mother talks about the ’70s where you had to line up to get gasoline. It definitely made a difference. Suddenly cheap oil was everywhere. Everything was cheap, cheap, cheap. The 1980s saw imports from China and the shift from manufacturing in the United States to manufacturing overseas. That meant much cheaper goods, and people could buy more things. There’s this materialistic culture that came out in the 1980s due to a combination of economic factors.

This is the time when all the magazines started, and shows like MTV Cribs. Suddenly our private life became very public. [For example,] the rise of the master bathroom. Before 1983, the bathroom was a place to do your business that you didn’t talk about. In 1983, there was a book published, the International Collection of Interior Design, that was talking about this sybaritic bathroom and the fact that this is now a place for luxury and to pamper and reward ourselves. You can have televisions and huge tubs and exercise equipment. That’s so ’80s, this rich wealth—or the illusion of it—on the back of a ton of debt. I think my parents are still paying off credit card debt from the ’80s.

Is there any other thing you find yourself obsessing over, in the area of growing high-end consumerism?

We have to remember the architects abandoned smaller housing clients in the beginning of the 20th century. That kind of abandoning the consumer across art happens in another place that we don’t think about: classical music.

In the ’40s and ’50s, this was past the age of a huge American influence of patriotism and Aaron Copeland and Samuel Barber. We were moving past that and it became highly experimental, highly modernistic, because it was funded by very wealthy art councils—that of course lost all of their wealth over the years. They drove audiences away. The same thing happened with architecture. Audiences didn’t want to buy a glass box because they work in glass boxes. Most people rejected modern architecture because it was modeled after the places that they worked. They wanted to separate their home and work life aesthetically.

I take it from the blog that you like modern architecture? What are some of the different forms of architecture that you really admire? Especially in the same era as the McMansion era?

I really love brutalism and big sculptural concrete buildings. I like that on the outside they’re so brutal but there’s something soft on the inside. The gentle sloping of the walls and the sculptural womb-like interiors. I think that some of them are really lovely. It’s just an aesthetic that you have to get used to. I think it’s sort of like blue cheese, it’s an acquired taste. I remember being fascinated with these buildings, and then eventually I started to like them. I feel the same way about post-modernism of the ’80s. Like Michael Graves and Robert Venturi, César Pelli. I became fascinated with them because I thought they were ugly. Then the more I looked at them, the more I liked them. It’s so funny the way that the mind works. Like, “Man, I really hate this, but I kind of like it at the same time.”

It’s kind of how I feel about interior design of the ’80s. I have a great love of Memphis Milano design, and all the kitschy stuff from the ’80s. I own a bunch of electric kitchen objects. I own a Michael Graves sugar bowl and cream holder, all that stuff. I like well-designed things. I kind of like something that’s bright and happy and kitschy sometimes. I have a great love for mid-century modern houses. I love them because they’re very modern but they still represent the overall shape of a home.

As far as architecture recently, I think personally that modernism has gone a little crazy. I definitely have a dislike for buildings where everything’s white. I can’t keep my own hands clean. I don’t like the sterility. Some white is lovely. I think the white kitchen has always worked. When your whole house is white, even if you have warm wood floors, still I think it’s sterile and cold.

As opposed to McMansions.

The thing about the McMansions is that they will always be built until we run out of natural resources or it becomes too expensive to drive. I think that they will always be built. This is talking about high architecture, which is something I try not to get into too much on the blog, just because you start to get bogged down with these aesthetic terms. There is a lot of architecture theory and philosophy. “Here’s my aesthetic, now I have to come up with the ten thousand reasons why this is a good aesthetic.”

Do you find it refreshing, talking about an area of architecture that isn’t so highbrow? Obviously, you do educate people. It seems you’re able to, like you phrase it on the blog, give a 101. These houses exhibit no advanced techniques whatsoever, it seems.

Yeah, I think a lot of the reason [McMansion Hell] is successful is that a lot of people hate these big ugly houses, but they don’t have the vocabulary to explain why. It’s like, “I hate it, it’s ugly, it’s huge.” The only thing they know is it’s huge. Not everyone wants to take art history classes.

Has anyone tried to actually argue with you in favor of McMansions?

Yeah, I think one guy did. I just deleted his email because he had some other issues. He was like, “I can’t afford to have a real mansion so why can’t I live in a play mansion?” Putting aesthetics completely aside here, there are two things you can’t defend. One is the lack of sustainability and the neglect of environmental issues. The second is that it’s a horrible investment! These houses don’t resell. The people who want to buy the McMansions, [they want] new ones going along with current trends. They don’t want your stupid house from 2005.

Yeah, it seems like, if you build something with all the specific things you want in a house, how do you expect anyone else to find that house perfect?

That’s the thing though, they were designed for everyone, they were designed on trends. We’re just stacking on desirable things. “Oh, the double sink in the master bathroom, that’s another thousand dollars added onto the value of your house.” It’s the dumbest shit ever. They were just built based on resale values. The fact is is that during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, you had to think about selling your house before you even made an offer on it. That just sounds absurd when you think about it. The point of view that this place that you’re supposed to spend years of your life could just be disposable. The houses aren’t really built to last fifty years.

Is there some situation in which these houses could have held their value better or would you just have to fundamentally change everything about them?

That’s the thing though, when you build a house based off of popular trends that you see on television, you’re building a house that you think that other people want, not what you want. The thing about what other people want is that it changes a billion times, especially in the age of the internet. Even if the housing bubble never burst, these houses that are ten years old now are still not going to sell. You can build a new one. If the bubble never bursts, we’re never going to learn our lesson.

The resale value is pitiful because at this point we’re starting to see that these houses [from the early 2000s] are starting to need new roofs. The roofs are so massive and complex that it’s probably cheaper to buy a new house than to re-roof the one that you have. You’re starting to see a lot of people sell their homes [as soon as they need maintenance]. It goes along with the trend of the disposables. You’ll see houses on the markets for hundreds and hundreds of days. The longer it’s been there, the worse it looks. It just says, “nobody wants this house.”

What are some trends ahead? You say nobody’s going to stop building McMansions even though they’re proving so unprofitable and unsustainable. What do you think is going to happen in the next ten, twenty years?

Why I say that is, the people who have the money to build these ridiculous houses, are going to spend the money to build these ridiculous houses. And so many of these houses of course ended in foreclosure when the bubble burst in ’08. Their equity tanked. For the rest of us, you see a trend of smaller houses appreciating faster than the larger houses. You’re seeing a cultural shift where people have fewer children. You’re seeing a shift where young people want to live in the cities.

There was a long period of time after the Great Depression where you were assumed to be doing well in life if you had a lot of stuff. Having your nice house and your family, that was the mark of your life. Young people today, the ones who grew up in the suburbs and McMansions are starting to feel like, “Yeah, I grew up here and I realize it’s incredibly isolating and lonely.” All of my experience comes from television, the internet or whatever. When it takes 20 minutes to go visit your friends and you’re relying on the car, yeah, you’re living a totally isolated life. When you live in the city you feel like you’re living in a community. There are people on the street to say hello to.

Right, you have more community. Although, the story of New York City over the past twenty years is one of housing booms and busts. I lived in Williamsburg a few years ago and it was full of these ghost sites where construction had just been halted. You’re surrounded by these eyesore half-built buildings. Now, of course, the housing boom is coming back, and we’re seeing a lot more of these condos, which also can clash with other architecture. What is the urban equivalent of the McMansion?

I think it’s called like the McLoft. I think that was coined by Paul Knox, the Dean of Architecture at Virginia Tech.

The reason is that in the earlier housing bubble, the builders would go to the 30 percent of people who aren’t married couples with families. They realized they could be making a shit-ton of money off of the divorces and the empty nesters and all these other people who have accumulated wealth but don’t need to live in a huge house. That’s why the condo thing has taken off. Especially the high-class condo. It’s kind of a risky bet, multi-family housing, it’s one thing to have one house empty, but to have entire buildings empty is even more disastrous.

That’s what happened in Florida after the bubble burst. I remember reading this one story about this one high-rise in Florida where there’s just one single person living in this huge building, this huge luxury condo. They showed a picture with all of the lights are out except this one light.

Have you seen any architectural effects of this? Like McMansions end up looking very different, which you blame on homeowners and builders working without architects. Have you noticed anything like that in urban areas, or is it different because architects still build even the bubble-driven buildings?

I think the architects are more involved in high-rise architecture because they get a much bigger commission than they do off of the McMansion.

So there’s a higher supply of willing architects?

Yeah, I think that a lot of them take the same look which is definitely a modern look. Still, I think a lot of the developers have a lot more to do with the design of the buildings than the architects do. In fact, I think a lot of them are designed solely by developers. They may hire an architect, but it’s not going to be a well-known architect.

After mid-century, like after Pruitt-Igoe fell in 1973, I think architecture just stopped working. It became kind of like a stigma to work without the guarantee of these buildings being occupied. I think they kind of got a bad rep for how they totally ruined low-income housing in the early 20th century. This is not an area I’m particularly an expert in, it’s only something I’m just now beginning to research. I’m definitely researching more of the low-density areas.

What other areas of architecture are you studying now?

Currently, I’m trying to understand the why’s of what they call modernist McMansions. Some popularity of modern architecture after the recession is really interesting. During bull markets, we tend to go highly ornamental in our interior design, especially in architecture. During bear markets, we tend to pare things down. Think of the early’90s, with the savings and loan crisis. That was when Ikea started and got huge. People got the white everything. It was the white Pottery Barn couch and the white kitchen and an emphasis on functionality. When markets are really good, you see more emphasis on luxury or superfluous assets.

So I’m starting to research the modernist McMansion. Especially the ones that are going up in L.A. that there’s all this riot about. They’re building these huge tract modernist houses, which is so mind-boggling to me because modernism has been the domain of architects for so long. Aside from your commie block office building, 90 percent of the time the ones designing modernist houses were architects. That’s what they learned in school, was how to design modernist houses. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Robert A.M. Stern, especially, brought back the study of traditional architecture into the schools after about a 50-year absence. You started to see architects becoming more and more familiar with the traditional forms. That stigma has sort of left, and you don’t have to be a modernist or super ridiculous like Frank Gehry to be an architect anymore.

You’d be surprised how much developers have control over our urban landscape, more so than the artists who design buildings. When you’re building a building for a function, you want it to perform that function. If the aesthetics are something that you can skimp on, then you skimp on them. It’s called having a high profit margin.

Has there been any positive aspect to the McMansion trend? Any result of the freeing from architectural norms, anything that anyone accidentally discovered?

I don’t think so. I think it’s one of the only architectural trends where that is not the case. They’re so heavily tied to speculation and cheap building techniques, and they have so many problems now as they’re coming to age. I think that the only positive is that people are starting to realize it’s not a good investment and it’s definitely not good for the environment as we get closer and closer to running out of oil. We just conveniently forget, or think it will never happen.

I’m so glad to hear that you already have plans for expanding this writing.

It’s been really wild how that happened. Going viral is strange. I literally woke up and suddenly I had 1,000 followers. Now I’m at almost 15,000. It’s just so crazy, I think the conditions have to be right. People generally want to be informed about the world. They want to know more about their landscape.

What are some common references you cite?

I always cite this one, it’s really the best book on this subject, A Field Guide to American Houses by Virginia McAlester. I’ve had a copy since I was in the tenth grade. It has my doodles from when I wanted to go to architecture school and be an architect. If you’ve ever had any questions about what that house is and what style it is, you can look in that book and learn everything you’ve ever wanted to know about American houses. It’s sort of an encyclopedia.

I love to read books by architecture writers, especially like Witold Rybczynski. He wrote this book recently about our suburban world called Mysteries of the Mall. I’ve read his books over the years. They’re really fantastic and this one proved to be no different. He’s someone I take a lot of influence from, who could write about architecture for the everyman.

I always have the same really boring academic books everybody else reads. I have always gone to the library to get books that I don’t have. The best thing is that I hoard these books of interior design from past decades, real primary sources. I can point to exactly what day and what time that this became huge, that’s the coolest part. I’m working on digitizing some of that stuff.

You’ve said that you’re going to do some longer posts on interior design too, right? So far, you’ve just covered those in your house-by-house posts.

Yeah, that’s called “A Field Guide to the Dated.” That’s coming after I get through the McMansions 101 series, which is all the exterior stuff, and talking about more important topics like the environment and sustainability. I’ve been amassing all these resources for it. I feel like they’re almost mini books in and of themselves. You want to know everything that was huge in the 1980s, so you can look in your house and see, that’s exactly the time period that came from or was influenced by. I can tell you. So that’s what’s on the docket.

I just love learning the 101 of anything, especially compressed. There’s a head rush when someone can compact a lot of information in a way that’s still actually useful and isn’t just a bunch of trivia.

Yeah. A listicle that’s like, “Here’s ten things you should hate about McMansions.” I can’t stand that format.

Right, you provide a framework.

It just says disposable to me. “Here’s a way to forget about it instantly.”