The year is 1993. Sitting in front of your trusty IBM, you insert a CD-ROM and watch as a mysterious tome tumbles down the screen, landing on the ground with a meaningful thump. This is the introduction to Myst, one of the most critically acclaimed PC games of all time.

Rand and Robyn Miller, the brothers who created Myst under the moniker of Cyan, Inc., could have rested on their laurels with their good reputation and successful mobile games. Cyan became known for its atmospheric worlds and insanely difficult puzzles; traces of its influence still show up today in games like iOS series The Room. But instead, the Cyan team has dreamt up a completely new world in Obduction, a game that launched Wednesday for PC with the help of more than 22,000 backers on Kickstarter.

“If you work with a publisher, you have a dozen new bosses that are telling you what to do. As an independent, we were a little worried (after the Kickstarter) we’d have 22,000 bosses,” founder Rand Miller tells the Daily Dot. “But instead people have been supportive and awesome, even about delays, telling us how excited they are.”

Obduction brings back the deeply immersive environments that are Cyan’s signature, but it presents a new story within them. You discover a strange artifact that transports you to an unfamiliar universe where you must explore to find out where you are and what’s happened. Your journey begins in a strange landscape dotted only by a farmhouse with a white picket fence, transforming the mundane into something foreign in an instant.

Miller says the idea of Obduction was knocked around the Cyan offices for 15 years or so before the team decided to actually create the game.

“We like this whole idea of being plopped into situations where you don’t know how you got there or why you’re there,” Miller says. “At some point someone said, ‘Hey, that sounds like when somebody gets abducted. That would be cool, it’d be like Myst in space.’”

While Obduction does make some nods to the Myst legacy, it is very much its own title, with a deep new universe to explore and new puzzles to solve. And in case you’re wondering if the difficulty of those puzzles is as notorious as you remember it, Miller laughs amiably when I ask him.

“You know, I don’t think these puzzles are that hard,” he says. “They are not going to be show stoppers. And let’s face it, the internet solves any puzzle you want. It’s not like playing Myst in 1993, where you either went to school or work the day after playing and maybe someone else was playing too you could talk it over with. Or you were driving to school or work, and it hit you: ‘Oh my gosh, I could try this!’ There was no internet to get an answer on then. But I think the puzzles are a little bit more in tune with not being frustrating.”

The Cyan team also knows the value of its history, making a point to add some nods to reward players who have been around since the Myst days, including the return of Miller’s brother, Robyn, to compose Obduction‘s score. Another thing Miller mentions is the use of the phrase “Who the devil are you?,” which Myst fans may remember Atrus exclaiming when you discover him trapped inside a book. Atrus was played by Miller back in the day, when using real people inside a video game was something the industry had rarely done before. Luckily, fans will see a return to that form in Obduction.

“We decided early on we’d give that a try because it’s a legacy of ours, and it worked well,” Miller says. “We definitely used the same kind of technology–RealVideo–and you’ll see the characters as you did before. We did it a little more sophisticated this time, and if you’re using VR you see them in 3D so they don’t look flat.”

While the Cyan team decided to use older technology for the sake of getting the nostalgic touches just right, they chose Unreal Engine to create the game itself, which is quite a step up from Strata, the software they used to design Myst during the ’90s. Despite the major upgrade, Miller says that they decided to also include the point-and-click functionality as an alternate option, in case some people wanted to play the old-fashioned way. That way, both newer and older gamers would feel welcome exploring the world of Obduction.

“One of the nice things about Myst is that I could sit my mom in front of the dock on Myst Island and it’s not intimidating,” Miller relates. “I just show her that all she has to do is click and she’ll go ‘Oh, I see! It’s beautiful!’ 3D interfaces can be intimidating, and it’s kind of nice to just click and move sometimes. At the least this mode lets people engage with our games really easily.”

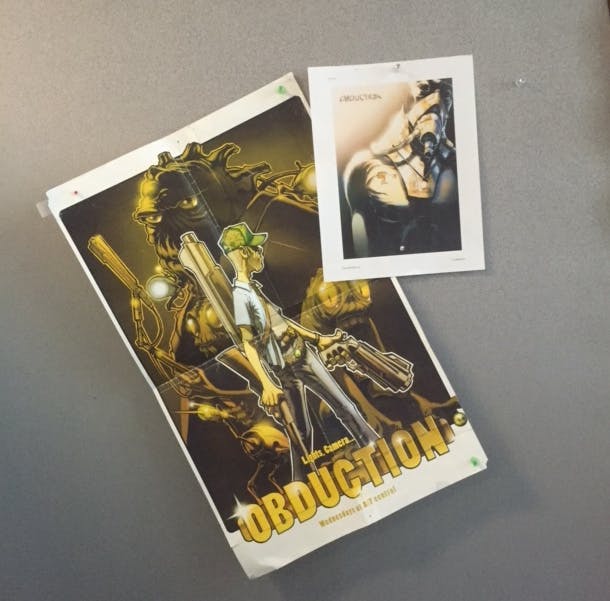

Since the idea of Obduction has been around for so long, it went through many incarnations before settling into what it is today. Miller laughs warmly as he recalls times when concepts of the game were more goofy or dark. But it resonated enough that even while Cyan worked on other projects, the team knew that they would eventually come back to it. An old Obduction poster behind one team member’s desk reminds Miller of how far the game has come.

“It’s kind of bizarre, because we look at that every day, and it’s got nothing to do with what we did,” he says. “But it reminds of us the roots.”

After Myst‘s heyday in the ’90s, Cyan continued to pursue the series through 2007’s Myst Online: Uru Live, which Miller says he is most proud of. Despite positive critical reviews, the game only lasted a year before partner GameTap shut it down. Miller vowed to resurrect it as an open-source project called the “Myst Online Restoration Experiment,” but plans fell off the radar when Cyan had to downsize significantly in late 2008. Miller candidly relates that mobile titles such as Stoneship and Bug Chucker kept the studio alive during those times. Today, Miller exhibits a strong sense of gratitude for where his company stands.

“Failures aren’t bad,” he says. “You look at them and learn, and you plan that if you fail you can still have a way to stay alive. We managed to claw our way back and move on. When you’re an indie company it’s tough, especially in certain climates where indies collapsed or got absorbed by bigger companies.”

Today, Cyan has a little over 20 employees, what Miller calls “a good size.” He is clear that thanks to Kickstarter, his company is able to return to form with its first full-length PC title since 2007’s Cosmic Osmo’s Hex Isle.

“The technology (of crowdfunding) allows us—a tiny little company in the middle of Spokane, Washington—to make a game and put it out where people all over the world can buy and enjoy it, and even help us fund it. That’s a liberating feeling and I couldn’t be happier about the freedom it gives us,” he says. “We’re in a cool phase right now where we’ve got this indie resurgence, the creative stuff coming from garages again. It’s full circle, because that’s exactly how we got we started.”