If you think an app has to ask permission to find information about you, think again. According to new research from Northeastern University, Android apps can track a user’s location even without access to the device’s GPS.

Guevara Noubir, a professor at Northeastern University’s College of Computer and Information Science, and a team of student researchers—Sashank Narain, Triet Vo-Huu, and Kenneth Block—set out to discover just how easy it is for an app to tap into a phone’s data by building one of their own.

The team crafted its own app—which, Noubir told the Daily Dot, could access the accelerometer, gyroscope, and compass without being granted access by the user via the typical permissions process.

The information from those sensors is uploaded to a server, where Noubir and his team host an algorithm that can sift through the data to infer a range of motion from the user. According to Noubir, the algorithm isn’t using anything proprietary; instead, it checks against OpenStreetMap, a free and collaborative public database of maps and roads.

Noubir and the researchers applied the algorithm to a variety of simulated and real road trips and tasked the system with determining the route the user took. They simulated trips in 11 major cities—including Atlanta, Berlin, London, and Rome—and drove more than 70 routes around the Boston area.

For each trip, the algorithm generated five paths that it believed to be the most likely route traveled. Fifty percent of the time, one of the five paths generated by the algorithm was the correct route.

While the results aren’t quite as accurate as a more straightforward means of determining someone’s geolocation, it still may come as a shock to Android users just how much information the device in their pocket is handing out without their knowledge—and what can be done with it.

The test app inferred the location of the user after the fact, but Noubir explained the task could be completed in real time. “As soon as the driver takes a couple of roads/turns, the probability of correctly infering the route will become quite good,” he said.

Noubir also explained that plenty of information about a person can be determined simply by knowing where they are going. The location a person leaves from in the morning and drives to in the evening is likely their home, for example. Having a piece of data as simple as that can lead to much more personal information being revealed via public databases.

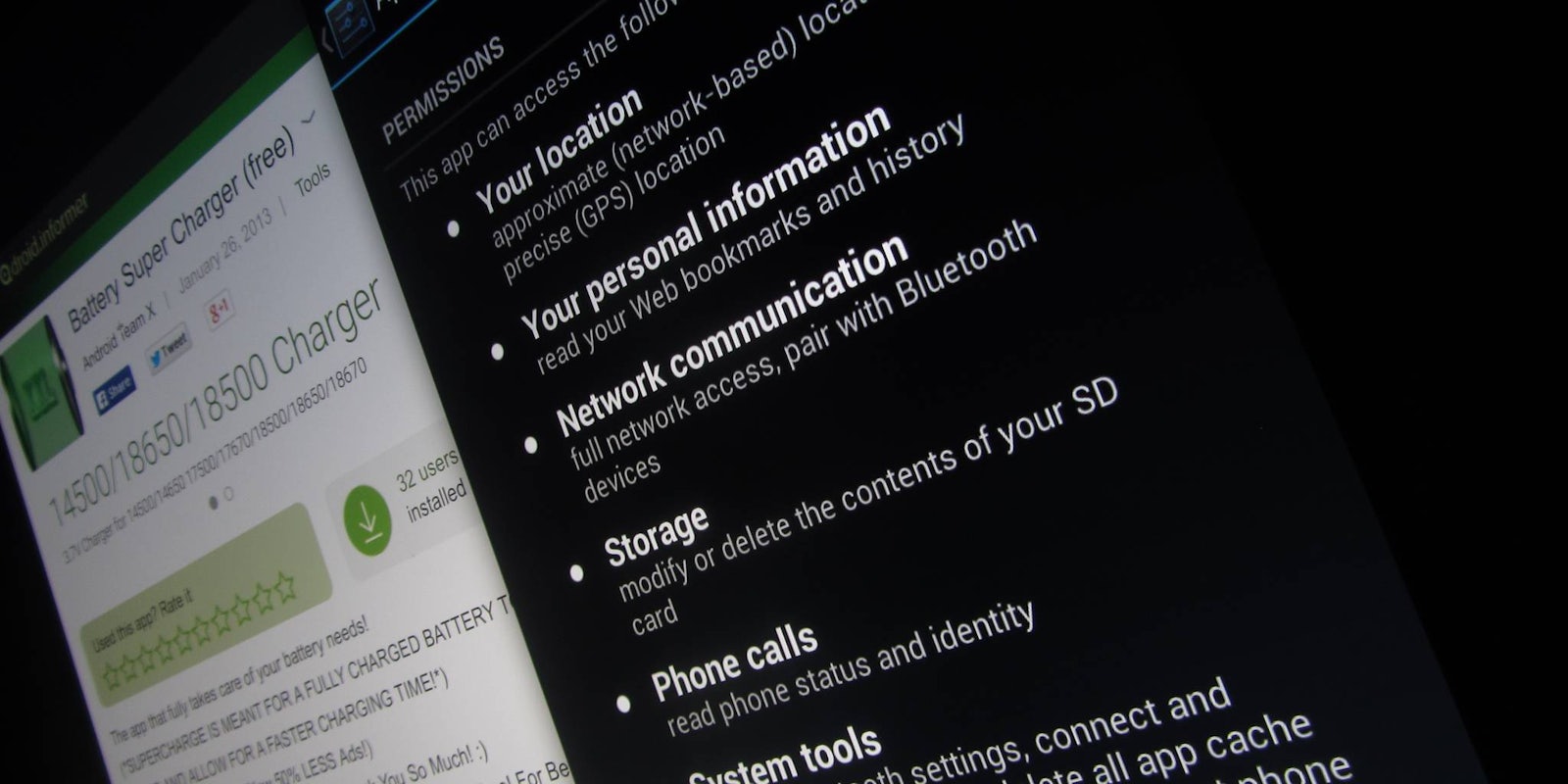

To avoid these types of “side-channel attacks,” Noubir suggests that users be diligent about monitoring the apps they choose to install and to not allow apps to run in the background. He noted it’s worth checking the permissions, but users should be aware “permissions are not enough to protect users’ privacy.”

He and his team are currently developing “mitigation techniques” with the hopes that they can limit the potential of the types of attacks they successfully simulated.

Google also has a role to play in ensuring the safety of its users. Noubir said it was his team’s opinion that Google “should continue [its] effort investigating and mitigating the potential of privacy attacks, in particular side-channel attacks.”

The most egregious of instances was the Brightest Flashlight Free app, which was secretly gathering and selling user location data despite its appearance as a simple flashlight tool.

The case resulted in charges from the Federal Trade Commission for consumer deception, and it caused the developer behind the app—Goldenshores Technologies, LLC—to agree to a settlement with the regulatory body.

The company behind Android has gotten better about giving users control over the access that individual apps have in recent years, adding a more detailed permissions manager in a recent version of the mobile operating system. However, there has still been plenty of apps that have subverted those rules and operate in ways that range from deceitful to malicious.

Google did not respond to request for comment.

H/T Phys.org