This post includes spoilers up to episode 4 of Andor.

Often overshadowed by complaints about bad dialogue and Jar Jar Binks, the Star Wars prequels offer some deceptively smart political worldbuilding. Not just in their depiction of a slowly-encroaching authoritarian takeover, but in the visual contrast between the Republic and Imperial eras. Andor provides an intriguing bridge between these periods, returning to Coruscant for its first onscreen appearance since the prequels.

In The Phantom Menace, the appearance of Naboo, and Coruscant was a shock to the system. Viewers had gotten used to the idea of Star Wars as a rough, lived-in setting; a universe of bounty hunters, gangsters, decrepit spaceships, and guerrilla fighters. But in the prequels, George Lucas introduced us to the tail end of Republic-era prosperity.

Referencing Ancient Rome and Art Nouveau design, Naboo is depicted as a wealthy, peaceful planet with rich artistic traditions. Coruscant is more ambiguous. The home of the Galactic Senate is dazzlingly high-tech but extremely stratified, ruled by stagnant and ineffective leadership. While the original trilogy leans heavily into Nazi-inspired imagery for the Imperial military, the prequels are more subtle, depicting a dull democratic government being smothered by commercial interests. From the opening crawl of The Phantom Menace, big business goes hand in hand with the rise of the Sith.

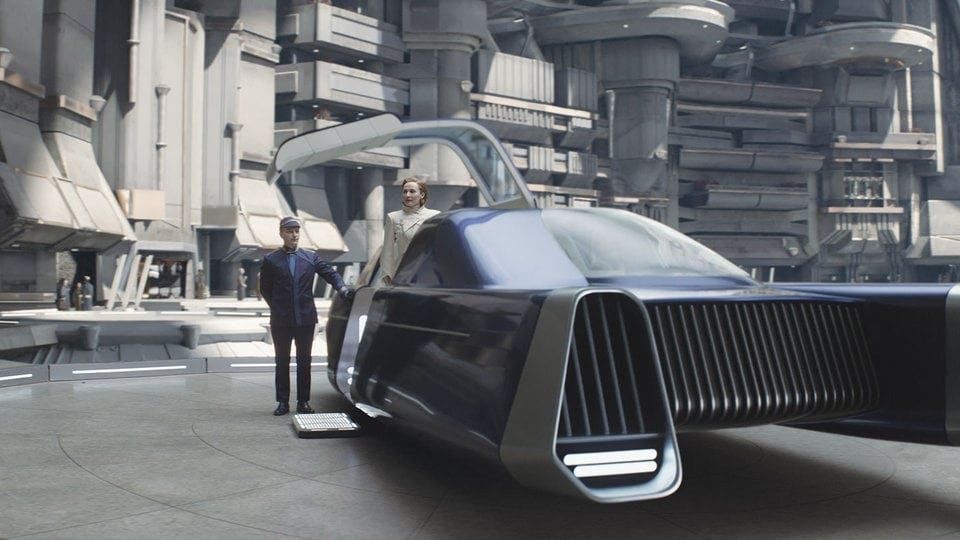

Andor follows a similar route, with rather more maturity. Cassian’s first scene involves a shakedown from a pair of corporate security guards. Petty authoritarian cruelty. And when we ascend to the upper echelons of the galactic government, we’re in for a surprise. Instead of being transformed into a cartoonishly evil-looking Imperial stronghold, Coruscant looks the same as it did twenty years ago. For someone like Senator Mon Mothma, life has barely changed.

Andor and Rogue One both explore the choice between keeping your head down, or taking a risky stand against an oppressive regime. Their main characters feel more precarious than the heroes of the Skywalker Saga, who exist in a fantastical adventure narrative.

Introduced as a Republic senator in the prequels, Mon Mothma goes on to lead the Rebel Alliance, eventually replacing Palpatine as the new Galactic Chancellor. Andor catches her during a transitional phase, secretly funding Rebel missions while living the luxurious public life of an Imperial collaborator. Wearing immaculate outfits and hosting dinner parties in a gleaming white apartment, she blends into the aristocracy of Coruscant.

Echoing the Canto Bight casino arc in The Last Jedi, this Coruscant sequence shows the galaxy’s upper classes living comfortably under Imperial rule. Mon Mothma’s true political affiliations are so dangerous that she even hides them from her husband, a socialite with no interest in rocking the boat. “Must everything be boring and sad?” he whines, when Mon yells at him for inviting her political rivals to dinner. To him, someone “cutting off the Ghorman shipping lanes” is a dry workplace dispute. To Mon Mothma, it’s a matter of life and death.

This kind of nuance is where Andor’s longform structure comes into play. The main Star Wars movies are quintessential blockbusters, typically concluding after the heroes defeat the villains in a big, dramatic battle. Everything must be digestible to younger viewers, and galactic worldbuilding is a secondary concern. Andor’s creative team have different priorities. Instead of reiterating the operatic supervillainy of the Imperial military and the Sith, we focus on the banality of evil.

Showrunner Tony Gilroy seems fascinated by middle-managers: The glorified mall-cops of the Pre-Mor Authority, the junior Imperial officers we meet in episode 4, and arguably even Mon Mothma, who can no longer leverage her status to make meaningful change. Pathetic individuals like Syril Karn and Timm Karlo (who betrays Cassian out of romantic jealousy) can do serious damage, but only by borrowing power from higher up the foodchain.

The real antagonist is the infrastructure of the state, illustrated through a sprawling ecosystem of evils big and small: police brutality, corporate overreach, planetary colonization, and mass surveillance. And the show makes it clear that these problems didn’t just materialize when Palpatine took over. Cassian’s home planet was invaded and strip-mined during the Clone Wars, when people like Padme Amidala were still nominally in charge. The late Republic era paved the way for the Empire to take over, and corporate interests played a central role in why and how that happened.