In a paper titled “Changing bodies changes minds: owning another body affects social cognition” published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, a European team of researchers examined the underpinnings of racism by recruiting participants for a virtual body swap.

Leveraging the visceral, immersive experience of virtual reality (VR), it’s entirely possible to give someone the experience of actually inhabiting a body different than their own.

This vein of research digs into a phenomenon known as implicit bias—the kinds of unspoken prejudices that are so automatic, we don’t even know they’re there. Implicit bias has long been measured in social psychology. Rather than asking a study’s participants to rate how racist they are on a scale of one to ten, for example, an implicit bias test would try to elicit the kind of snap judgments as brief and automatic as what flashes through our heads as we pass a stranger on the street.

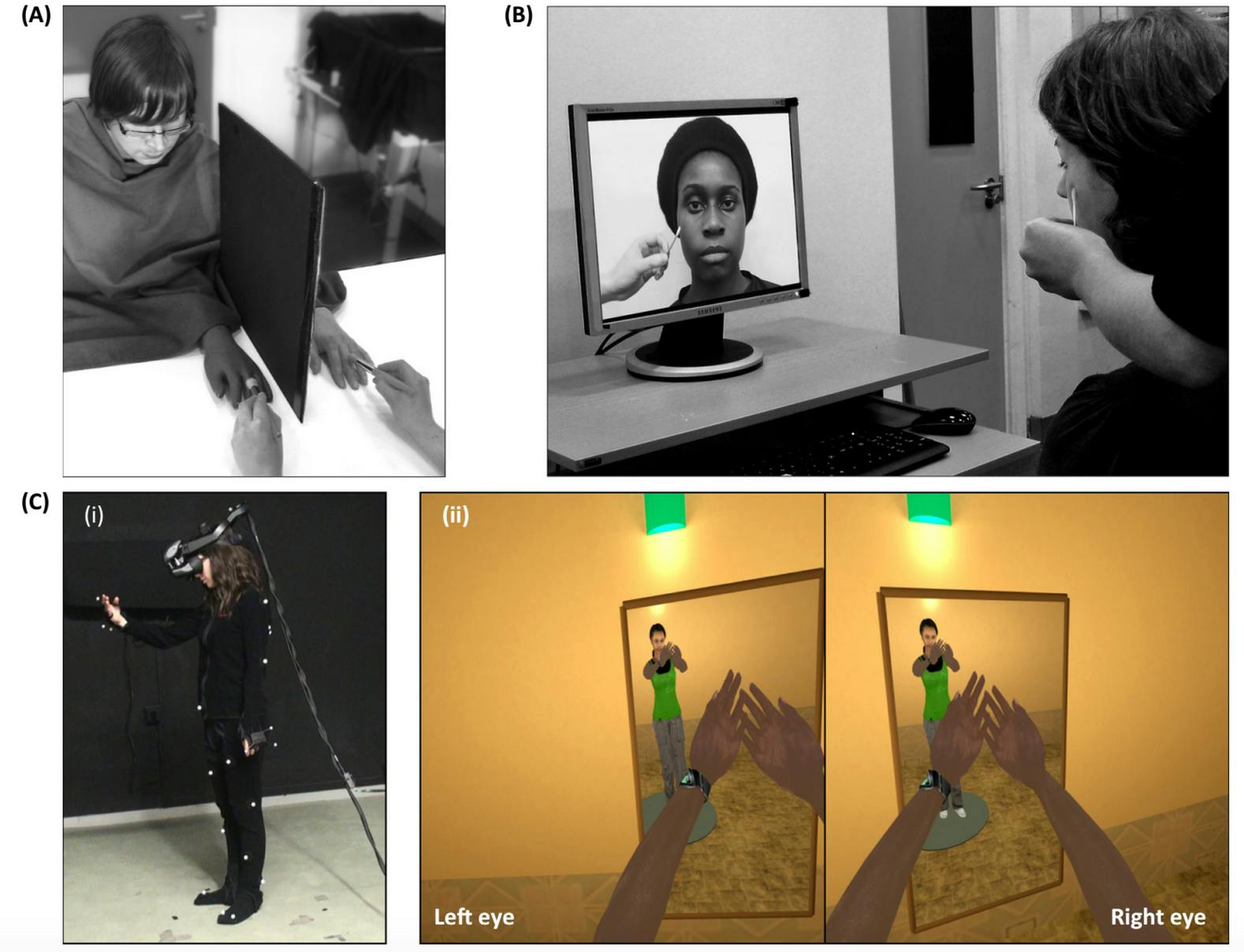

For VR studies examining racial biases, that’s as simple as making a light-skinned person feel connected to a virtual, darker skinned self—a thought experiment pretty much impossible without the immersive potency of VR. The effect is achieved by outfitting participants in VR headset with built-in head tracking and motion capture capabilities that sync actual movement to virtual experience:

“The participant’s own body is substituted by a virtual body, viewed from a first-person perspective, with a motion capture system so that their virtual body moves with their real body movements.”

Evolving from cruder methods, VR is a natural extension of research examining the ways that people think differently when made to feel like they are part of a meaningfully different social group, known as an outgroup.

“Over the past 20 years, advances in experimental psychology, cognitive neuroscience and virtual reality have allowed scientists to experiment with a fundamental element of self-awareness, the sense of body ownership, using a range of bodily illusions,” the study’s authors posit. “These findings suggest that changes in the perceived similarity between self and others, caused by shared multisensory experiences, might ‘bridge the gap’ between the basic, perceptual representation of bodies, and the complex social mechanisms underlying much of our everyday social interaction.”

What’s most exciting about this channel of research is that it gets at the kind of complex, subtle prejudices that most people can’t even articulate if asked directly. Those deeply ingrained systems of racial bias are tenacious. Unlike overt forms of racism (hate speech, for example), implicit biases rarely express themselves in such a straightforward way, which makes their underlying framework of prejudice even more difficult to confront or disrupt.

The idea is remarkably simple, in spite of the sophisticated technology that makes it possible: when we try living in someone else’s skin, empathy arises naturally—a side effect of stepping into a different virtual body and taking a look around.

H/T Business Insider | Photo via pestoverde/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Fernando Alfonso III