This review includes spoilers for The Book of Boba Fett episodes 1 and 2.

With The Mandalorian and now The Book of Boba Fett, Disney+ has perfected a unique brand of TV storytelling—one where fandom nostalgia and expert production design are crucial, but things like “plot” and “character” are a distant afterthought.

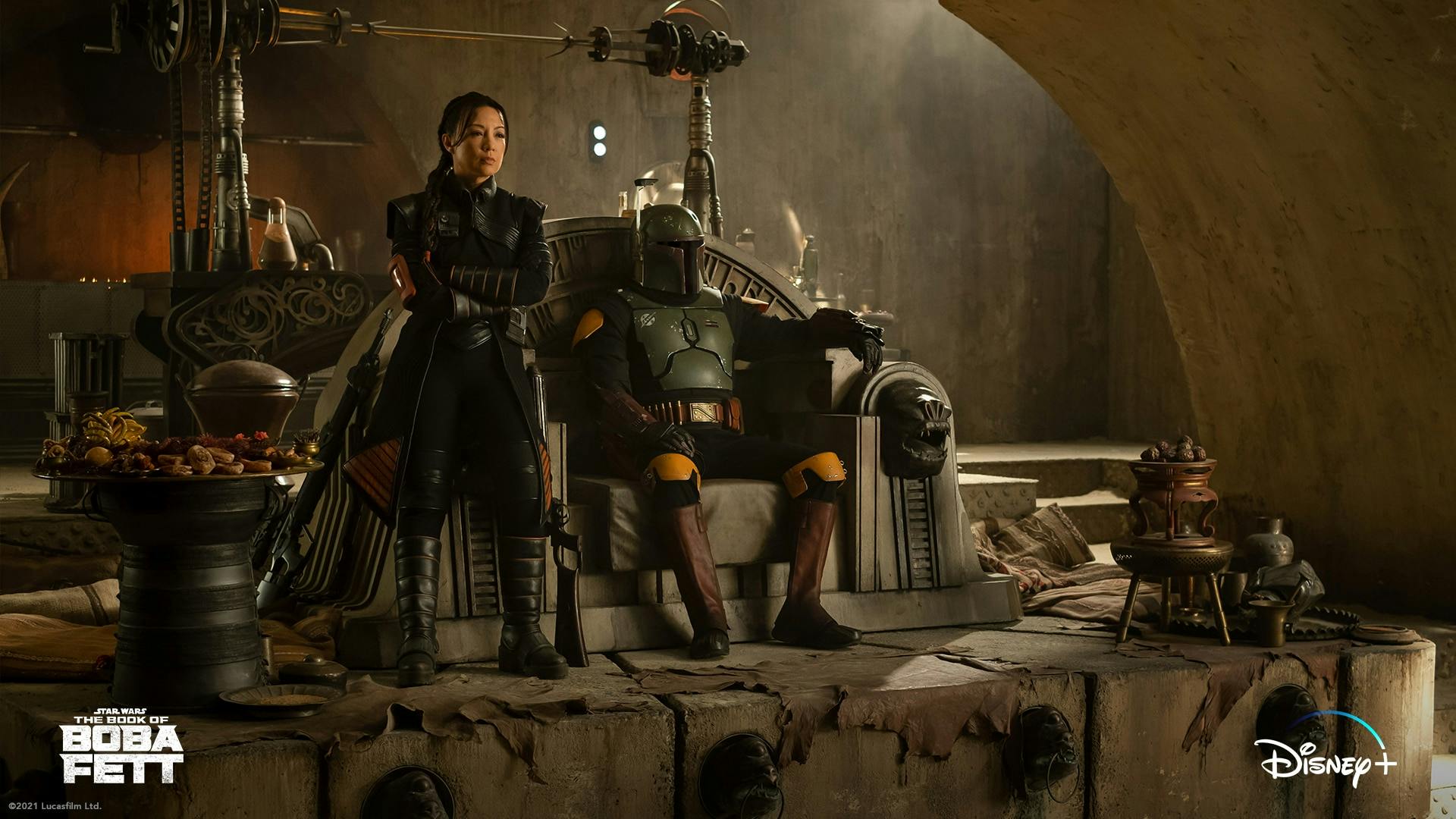

Two episodes in, Boba Fett has offered a glorious showcase for the costumes, creatures, and vehicles of Tatooine. The show’s narrative purpose is harder to discern, as Boba slowly perambulates between basic exposition, fight scenes, and laborious flashbacks to his recent past—a matryoshka doll of backstory management, slotting in between his Attack of the Clones origin story and his Mandalorian cameo.

In the real world, Boba gained a cult following thanks to merchandise and Expanded Universe spinoffs in the 1980s and ’90s. Like The Mandalorian (which shares the same showrunner, Jon Favreau), The Book of Boba Fett leans heavily on nostalgia for this era. Evolving beyond his one-dimensional role as a tertiary villain in the Original Trilogy, Boba Fett is reborn as a heroic and surprisingly moral figure, beginning with his escape from the Sarlacc pit.

After being kidnapped/rescued by a community of Tusken Raiders, Boba claws his way to the top of the Tatooine food chain, conquering Jabba’s palace. This allegedly makes Boba a crime lord, but so far he’s too nice to do any cold-blooded murder or drug dealing, the cornerstones of his new profession. This is, after all, a Disney production.

Embracing the franchise’s Wild West roots, the first two episodes track Boba Fett’s journey from Tusken prisoner to Tusken leader. A classic adopted-by-the-natives tale. The traditional formula involves a white savior mastering the skills of an indigenous community, although this story has a different weight with a Māori actor in the lead role. (Temuera Morrison’s Māori heritage influenced his version of Boba Fett, and elements of Mandalorian lore.) The general framework remains the same, however, with Boba as a human hero among enigmatic aliens.

The Tuskens echo “noble savage” stereotypes, a nomadic culture with sympathetic problems (they’re oppressed by tech-wielding offworlders), generally portrayed in a condescending light. Boba quickly outwits his Tusken captors, impressing them by killing a desert monster and then learning Tusken martial arts. Episode 2 sees him teach the Tuskens how to ride some speeder-bikes and raid a freight train—another twist on a classic Western trope.

Boba is resultingly rewarded with a Tusken vision quest and his own gaffi stick, a weapon inspired by the Fijian totokia. But while he dances around the fire with his new friends, we know he’s destined to return to the “civilization” of Mos Espa. The Tuskens will presumably return as allies in later episodes.

All this is to say that while Star Wars thrives on vintage tropes and callbacks, The Book of Boba Fett is just too conservative. After two very similar seasons of The Mandalorian, Jon Favreau’s formula is getting old. The show also takes it for granted that we already care about Boba Fett. A dicy assumption because for many viewers, Temuera Morrison is better known as the face of Jango Fett and the Clones. Boba Fett is just some guy with ten minutes of screentime in the OT.

So far, the show is relying on Morrison being very watchable (which he is!) and Star Wars fans tuning in for something that visually resembles the movies. But The Book of Boba Fett lacks the emotional and thematic depth of the films—and struggles to explain what the title character actually stands for.