Imagine putting the brain power and skill of the world’s best surgeons into a robot that could perform surgery better than human doctors. At Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, DC, scientists built a robotic system that can do just that.

The “Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot,” or STAR system, is programmed to autonomously execute surgery on soft tissue. In its early testing, it’s being tasked with procedures on pig intestines. Researchers compared the outcome from STAR’s surgeries to others performed by humans, including robot-assisted surgery, and found that STAR was more successful. Their work was published in Science Translational Medicine this week.

Current robotic surgery techniques like the Da Vinci System still rely on humans to control them—robots are an extension of surgeon’s vision and dexterity, executing tasks that the surgeon’s hands are controlling. With STAR, the entire procedure is done autonomously, controlled by an algorithm and executed with the help of infrared cameras and 3D-imaging.

“You can potentially have a clinical outcome or functional outcome that’s better than it’s ever been done before using currently clinical standards.”

As Dr. Peter Kim, vice president of the Sheikh Zayed Institute for Pediatric Surgical Innovation at Children’s National, explained, while surgical approaches have changed through the decades—like manual, minimally invasive, or robotic-assisted surgery—the complication rates have not decreased. Researchers aim to use STAR to result in better outcomes for patients.

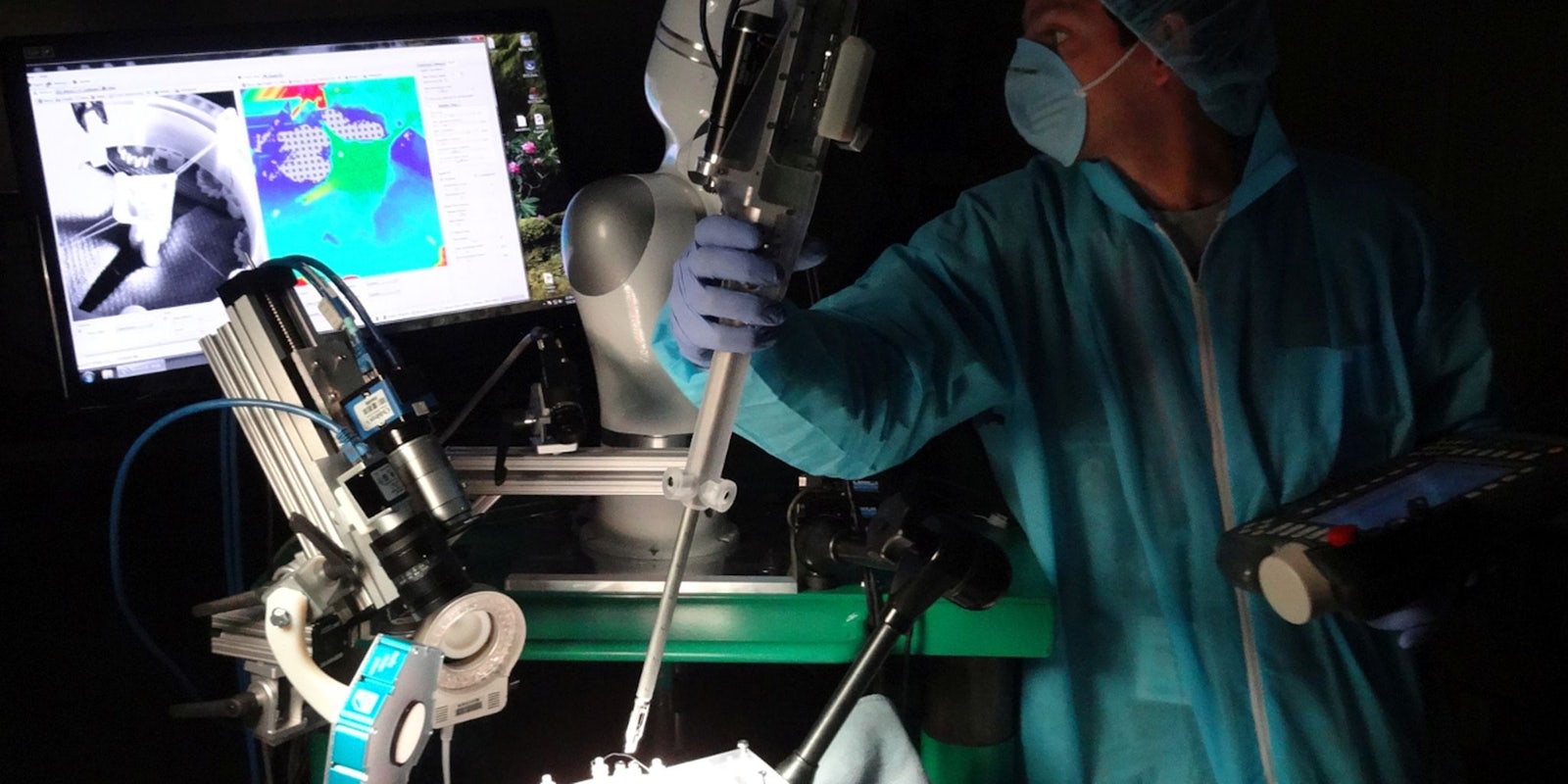

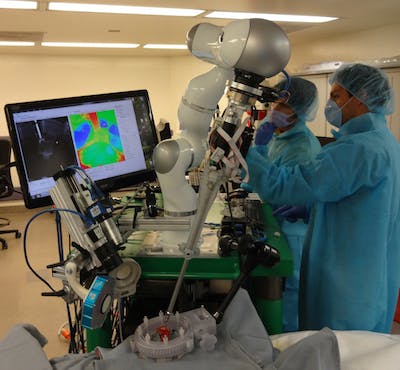

The STAR approach is the first automated surgical system and improves upon existing robotic systems by changing the vision, dexterity, and intelligence of the hardware itself. STAR contains a lightweight robot arm (the LWR4+ from KUKA Robotics), with a suturing tool on the end. The tool is powered by microcontrollers and two motors, one that maintains articulation, and another that controls the needle.

The bot doesn’t know where things exist in space, so in order to understand where to execute surgery, a camera creates a 3D-point cloud that allows the robot to reference objects, or tissue, in a way it understands. Then, fluorescent dyes are added to the tissue giving STAR reference points for sutures which it can see through a near-infrared camera.

Essentially, the imaging system gives the robot super-human vision capabilities, and can precisely track dynamic changes in the tissue that, to humans, looks pink, squishy, and bloody. A haptic sensor improves the robot’s dexterity as it gently performs its actions.

What’s most interesting, Kim said, is the software that controls it all.

“When you add a little bit of intelligence to the tool itself, and if you improve the vision part, and then improve on the dexterity part, you can potentially have a clinical outcome or functional outcome that’s better than it’s ever been done before using current clinical standards,” he said in an interview. “[It can] mitigate against complications like leaks, or things getting disrupted.”

The algorithm that controls the robot is based on the surgeons’ consensus of the best techniques, reported literature, the size of the tubular tissue, and the degree of formability and mobility.

Essentially, the software is programmed to execute surgery the way the world’s best surgeons would. If the tissue moves, the vision system lets the robot see the changes, and it automatically adjusts suture placement, and continues on.

Kim said 60 percent of the time the machine executed the procedures autonomously, and 40 percent of the time, researchers checked to make sure it was executing correctly and made minor adjustments if necessary. When compared to human surgeons, STAR performed better based on measuring the quality of the sutures, suturing space, pressure it takes to cause a leak, and any hesitations or mistakes.

The algorithm is pre-programed for each surgery, meaning STAR isn’t artificially intelligent, yet. Kim said the goal is to have STAR systems learn from each surgery and develop better, more accurate and safe procedures overtime.

“In the future, what I would love to see, is anytime anyone uses a machine like this, it’s stored in a cloud, so that it will develop cumulative knowledge based off all surgeons currently practicing,” he said. “Wouldn’t it be nice to get the best decision based on collective experience.”

Eventually, these robots could change and improve care in areas where access to the best doctors isn’t possible. For instance, getting patients world-class care without needing to transport them to top surgical facilities would be a huge advantage.

Kim said surgeons shouldn’t worry about robots leaving them jobless, as these autonomous systems will create new opportunities to work with machines and intelligent technologies. And ultimately, it benefits the patient by providing improved care and reduce complications.

“Human touch and compassion and care will be better if outcomes are better,” he said. “This enables you to have a conversation with your patients with a positive outcome, rather than saying, ‘I tried this, and it didn’t quite work out, but I still cared for you,’ kind of argument.”

There is no timeline for when STAR will be tested on human patients, but Kim said it’s possible in the next few years. Now that the STAR system already outperformed humans, it’s entirely possible that the top surgeons of the future will be robots.