My mother always emails or calls me on March 21. It’s the anniversary of the day we left the Soviet Union. I call or email her on May 26. It marks the day we arrived in the United States. In between are two months and five days. We spent them in Rome.

The United States does not accept as refugees those who are already there. As Jews who had fled the Soviet Union, we could not go to America directly. We had to be processed in a third country, in our case Italy, before we could be admitted to the United States. My father, who had come to the United States a year before us, flew there for a reunion. We were lucky—the United States would take us. There was a community ready to welcome us, which had fought for years to help secure our release.

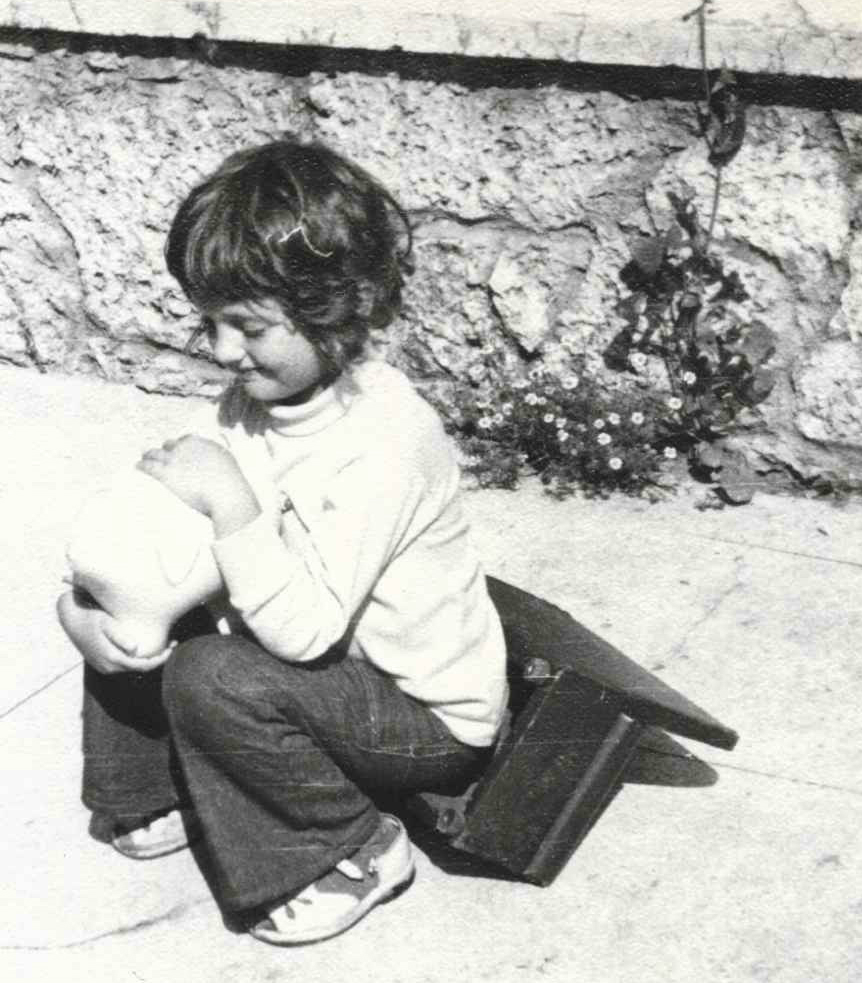

I don’t remember much about those two months and five days. I was five. I remember the beach, the ruins at Ostia Antica, strawberry yogurt. Seeing my father for the first time in a year. But I think of that spring every time I see photographs of Syrian refugees today. I met a few of them last summer, doing field research in Jordan and Lebanon. The children look much like I did back in the spring of 1976—rumpled, confused, clinging to their parents. They don’t know the language. The culture is strange. The food is similar, but not quite right. Their parents are unmoored, different from how they were at home. Me, I was impressed by gumball machines and terrified of the red sauce on pizza. The white pizza (pizza bianca) was ok.

There are voices in today’s political debates in Europe and the United States that hold that the Syrians are an entirely different matter from my mother and me. We were “Europeans.” My parents fled persecution, not war. But should ethnicity, nationality, or even the specifics of the hazards one flees matter? Moreover, the rules change: In the 1930s and early 1940s, European Jews trying to get to America were turned away because they were potential security threats, because their culture was foreign, because of their religion.

The United States, this nation of immigrants, had its better moments. One million Vietnamese came to this country after the Vietnam War, despite all the same fears about terrorists and collaborators. It had its worse ones: The difficulty of admitting Afghan and Iraqi advisors, interpreters, and other colleagues who helped the United States, despite repeated promises, points to the difficulties of adapting a system designed to make it difficult to enter to the requirements of a population in immediate need of rescue. To let more Syrians in would require changes to policies and procedures, and those simply will not happen in the current political context. And that context is one that does not want the refugees here, as the admission figures to date indicate.

Luck or no luck, we contributed, and the United States benefited from us being here, even as we benefited from the opportunities we had.

But some refugees kill! Some are terrorists! Some may harass women. They will be burdens on our social welfare systems. Of course, we’ve all seen the Facebook memes that tell us that toddlers with access to their parents’ guns are more deadly. That European terrorists were more lethal in the 70s and 80s than today. Not only are most terrorists homegrown, not immigrants, but most of America’s domestic terrorists are white men, whether we admit that their politically motivated murders are terrorism or not. And do I really need to tell you about the level of harassment a woman faces going about her day in the United States, directed at her by men representing a smorgasbord of ethnic and national backgrounds? Assuming roughly half the people reading this are women, and they can explain to anyone who is confused, I imagine I do not.

My parents and I were not burdens on the United States. My father is a prominent mathematician. My mother worked her way up the corporate ladder and later started a successful small business. I’ve done pretty well, too, if I do say so myself. So have my sister and brother, born in this country. Not everyone was so lucky. Not all of those born here are so lucky. But luck or no luck, we contributed, and the United States benefited from us being here, even as we benefited from the opportunities we had.

Forty years ago, I was a little girl in Italy, between countries, speaking neither Italian nor English. I had a bright future ahead of me, because there was a place for me to go. Right now, there are millions of Syrian children in Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Europe, and elsewhere. Their futures are murky. Unlike my family, in most cases, their parents want to take them home. They want the war in Syria to end, and they want to return. If this proves impossible, it horrifies me to think that there is not a safe haven for many of them.

I am deeply disturbed by the terms in which this debate is framed, by the desire to deny entry rather than to find ways to help.

As I noted, I do not expect the United States to allow large numbers of Syrian refugees into this country, despite the best intentions of our leaders to increase numbers. I see the struggle in Europe to accept more, and I laud the countries that have been generous, including Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, which have opened their borders to millions of people, far more than Europe will, and myriad more than the United States. It is my fervent hope that Syria can be stabilized and those who want to can return and rebuild. But I am deeply disturbed by the terms in which this debate is framed, by the desire to deny entry rather than to find ways to help. And I worry about the implications of this for our societies. I worry particularly about the United States, both because it is my adopted country, and because it is a nation that is at its best, strongest, and truest when it welcomes strangers in need. I worry that the world, and this country, has turned so much less welcoming. But I also know that these things can change.

The support my family and those like us got was driven in part by people organizing, fighting for us when we could not fight for ourselves. One way in which our world has changed over the last 40 years is that the Internet has provided an ever-growing ability for all of us to amplify our political voices. In the debate today, I worry that hate and fear may be winning out over rationality and kindness. But it’s not too late to change that.

Olga Oliker is a senior adviser and director of the Russia and Eurasia Program at Center for Strategic and International Studies. Prior to joining CSIS, Oliker was director of RAND’s Center for Russia and Eurasia. She has been published in the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, CNN, U.S. News and World Report, among others. She holds a B.A. in international studies from Emory University and an M.P.P. from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.