Presidential primaries are typically contentious and competitive, but this is ridiculous.

The race for the Republican party’s nomination has been successfully lulled into the gutters of rhetoric by frontrunner Donald Trump, a man who spent much of the past year mastering the art of the put-down and has now led rivals Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz into a tournament of schoolyard taunts, ranging from criticisms of each other’s appearance to last night’s debate in Detroit, where Donald Trump literally defended the size of his penis.

Not helping the matter, the audiences have eaten up the sophomoric display like Mad Max war boys. As the Republican field narrowed from 17 candidates to four or five, audiences in South Carolina, Texas, and now Michigan have cheered and jeered at their favorite barbs, perceivably unfair lines of questioning from the moderators, and the indiscernible, overlapping squabbles that have come to define the GOP race for president.

Audience screamer is #GOPdebate night highlighthttps://t.co/gz9KYFBfsc

— FOX & friends (@foxandfriends) February 26, 2016

https://twitter.com/omriceren/status/705590111459794944

During the break, please eject the entire audience. Thank you. #GOPDebate

— Jon Gabriel (@exjon) March 4, 2016

The audience at every Republican debate was teleported from a “Married With Children” taping in 1989. #GOPDebate

— Mike Drucker (@MikeDrucker) February 26, 2016

According to security, they have had to kick out +50 people inside the debate hall for being drunk & disruptive

— Benny Johnson (@bennyjohnson) March 4, 2016

The presence of raucous and opposing supporters battling it out in the stands is not only lessening our chances for substantial debate—it’s feeding into the system that allows our process to resist being a noble practice in democracy and instead mutate into a national embarrassment. Living in the United States and complaining about the state of debates is a bit like living in Seattle and complaining about the rain. But allowing audiences to actively encourage immaturity and ad hominem tactics not only encourages candidates to change nothing—it tells viewers at home it’s OK to expect nothing to change.

The presence of raucous and opposing supporters battling it out in the stands is not only lessening our chances for substantial debate—it’s feeding into the system that allows our process to resist being a noble practice in democracy and instead mutate into a national embarrassment.

The unruly atmosphere encouraged and created by the audience raises the question of what purpose the audience is serving to begin with. Are they meant to provide candidates with live feedback to their positions and stylistic tactics? Or, like the laugh track on a sitcom, are they meant to help home television audiences know when to cry and when to laugh? Most moderators typically keep punditry at arm’s length, leaving us, the viewer, unarmed with a talking head to let us know how we should feel. Are the constant and discomforting reactions from the crowd supposed to supplement us with support for our own outrage or glee?

In this way, the audience plays the same role offline as the hordes of mocking and sarcastic tweets play online. Twitter users, myself included, have made a full-time hobby out of watching debates and waiting for the next slipup, the next guffawing insult, the next GIF-able moment. It is hardly the intellectual pursuit many users might pretend it is.

Twitter, however, is what you make of it. It can, like the live audience, be a place for mockery and derision of superfluous gaffes and personal tics, or it can be a place for fact-checking, live-reporting, and reactions from scholars and luminaries. When Trump cited former Secretary of State Richard Haass as an influence on his foreign policy, many people retweeted the reaction of Haass himself.

as @CFR_org president I do not endorse candidates. What I have done is offered to brief all candidates, & have briefed several, D & R alike.

— Richard N. Haass (@RichardHaass) March 4, 2016

The crowd, however, is limited to the confused and binary response afforded to an audience—just enough to egg on or protest a candidate. Perhaps the goals are more noble and my protestations too cynical. Perhaps, in a quest to bring truth to power, the debate audiences is meant to act as The Voice of the People, loud and proud to sniff out a false promise or rhetorical trickery without letting any candidate escape unscathed. If true, the process by which audiences are selected renders this point beyond moot and, in fact, contradicts any desire to hear what the average voter has to say.

Debate audiences are largely chosen by state parties, which typically hand out tickets to state party workers and donors, and an equal number of tickets are then distributed among the candidates. After Trump accused a booing New Hampshire audience as being stacked with bigwig GOP donors in favor of Jeb Bush, noted Trump mouthpiece Breitbart News sought a breakdown of tickets from the South Carolina GOP for the Feb. 13 debate. Out of the 1,600 seats available, 550 went to the Republican Party, 100 each went to the six remaining candidates, and the rest were distributed among the venue and co-sponsors CBS and Google.

It is extremely difficult for the average voter—a rank-and-file Democrat or Republican without party or candidate connections—to find their way into a debate audience.

It is extremely difficult for the average voter—a rank-and-file Democrat or Republican without party or candidate connections—to find their way into a debate audience. For last night’s debate at Detroit’s historic Fox Theater, the state GOP allowed aspiring audience members to fill out an online form in order to be submitted for a raffle for the 50 remaining tickets after the usual handouts to party leaders and Fox News network officials. For those 50 tickets, however, the state party received more than 21,000 submissions.

What that leaves then is an audience that Trump rightfully called out for overflowing with donors and organizers who expect such favoritism from their chosen candidates. The process encourages strong divisions, as Thursday night’s debate in Detroit saw when candidates frequently had to pause in answering moderator questions to allow the crowd time to sort itself out. The candidates frequently had their responses interrupted by ranging hoots and murmurs. Presidential debates should be no place for hecklers, yet the continued enabling of the audiences has made it natural to expect whooping and insults in response to juvenile and personal barbs from the candidates.

And what the audience wants, the audience gets. Part of the reason the debates have descended so far recently has been rallies the candidates have held themselves. Trump events have become famous for their disorderly and unmanageable crowds, with the candidate himself typically having to order out protesters. The real estate magnate’s rallies have even gotten violent and contentious—a Black Lives Matter protester was reportedly punched and hit with racial slurs at a Trump rally and a different group of black students at a Trump event in Georgia were forcibly removed by local police at the behest of the candidate himself.

Supporters behave at the example of their candidate, allowing themselves to be pulled towards or away from different poles of behavior and conduct.

Such incidents, especially when led on by the candidates themselves, only reinforce the contentiousness of this primary election cycle and the standard of behavior for candidates and supporters alike. Supporters behave at the example of their candidate, allowing themselves to be pulled towards or away from different poles of behavior and conduct. Such feedback creates a loop which encourages candidates to chase the dragon of crowd reactions.

Such is the fate of Marco Rubio, a candidate who once pledged to stray away from personal attacks and is now debasing himself with accusations against Trump on matters as policy-heavy as his makeup or whether he wet his pants in the backstage of a debate. Trump is happy to engage with Rubio—or anyone, for that matter—on such a level, but even happier are audiences begging for candidates to get personal. It’s a well-known paradox that, despite how voters might tell pollsters how they feel about negative political tactics, they work. It is (or at least should be) the job of candidates and the media to keep our national discourse away from this instinct and lead supporters by example through detailed and nuanced debate.

By that measure, the 2016 GOP debates have summarily failed at preventing our electoral process from being led into the gutter by the animalistic reinforcement of childish rhetors by audiences thirsty for blood. If the candidates cannot prove themselves capable to resist the temptation of getting one more laugh or cheer, it is up to the TV networks to pull the audiences out of the equation. Their atmospheric purpose as resident Voice of the People is not only poorly served but a misguided preventative measure against viewers making up their own minds. It is not enough to console the crowd for respect, as FOX News’ Bret Baier and Megyn Kelly did last night. Remove the audiences in a desperate hope the candidates will recognize the seriousness of their quest to lead the people instead of feeding into their most basic demands for entertainment.

Gillian Branstetter is a social commentator with a focus on the intersection of technology, security, and politics. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, Business Insider, Salon, the Week, and xoJane. She attended Pennsylvania State University. Follow her on Twitter @GillBranstetter.

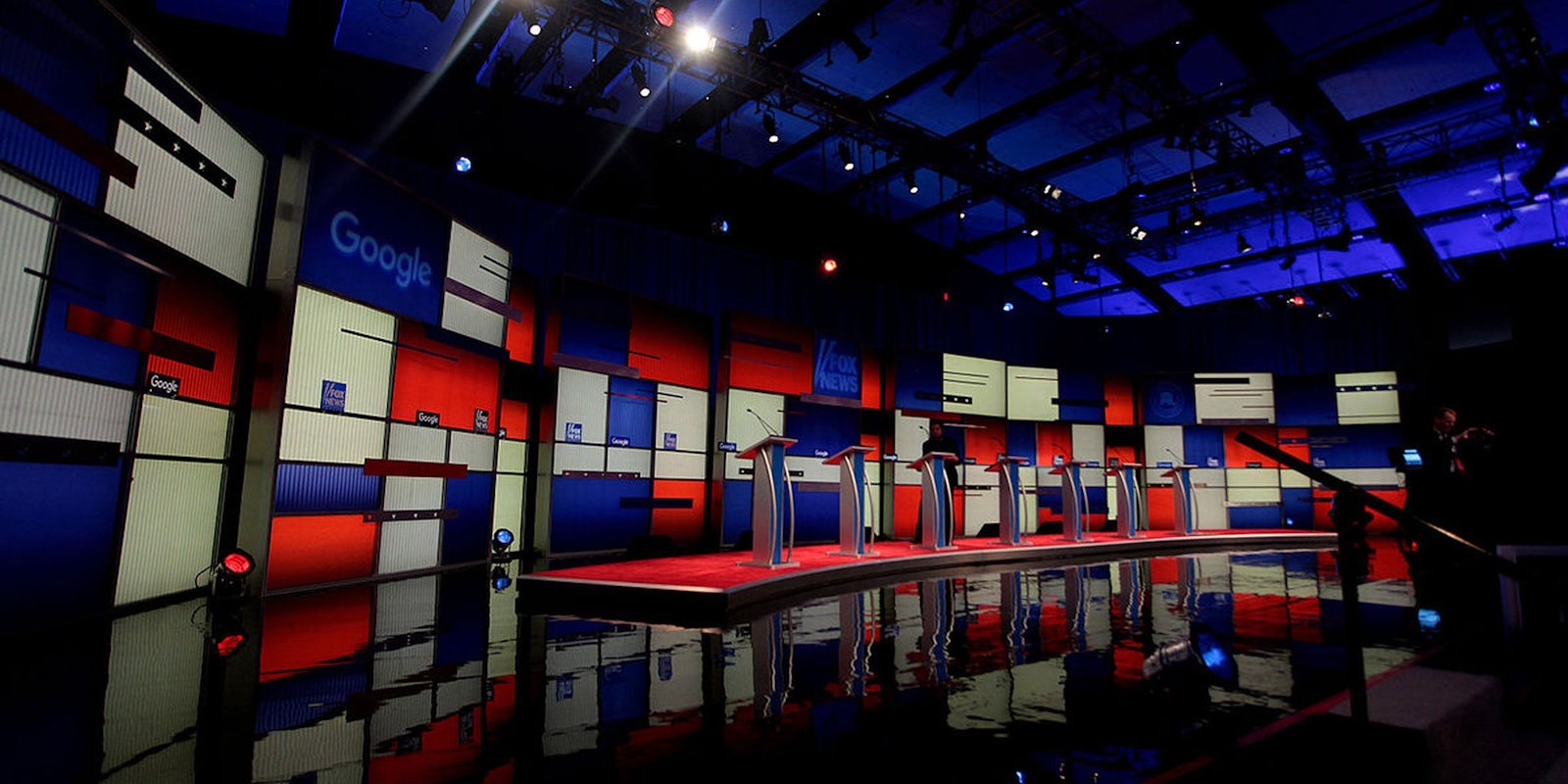

Photo via Gage Skidmore/Wikipedia (CC BY SA 3.0)