On Jan. 11, 2016, Peach was dubbed a “new social media obsession” by the Huffington Post, an app “taking the tech world by storm,” according to the Guardian, and an app “for the kids at tech’s cool table,” Recode said. A mere four days later, it was pronounced “dead,” disappearing into the digital ether. Such a short, spectacular life and demise is par for the course in the app world—to state the obvious, few apps can have the lasting impact of Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram—but when I logged on recently for the first time in months, there were still some active Peach users with green dots by their names amid all of the other accounts whose last log-on time said seven months ago.

Who uses an app after it’s been declared dead—and why?

A small but dedicated group of internet kids have retreated to Peach and turned it into equal parts pastel-laden secret clubhouse and online journal. The app’s lack of popularity is part of its appeal: You can drop whatever persona you might have on Twitter or Instagram and receive honest, supportive affirmations in response.

“The way I use it and the way my friends on there use it is, like, post what you wouldn’t want anywhere else on Peach,” says Tatyahna Cameron, 24. “I’ll complain more about guys who follow me on Twitter, or I’ll talk more about serious family stuff and weight loss stuff. There are a lot less people, and all the people on there are doing it the same way, so it feels safer.”

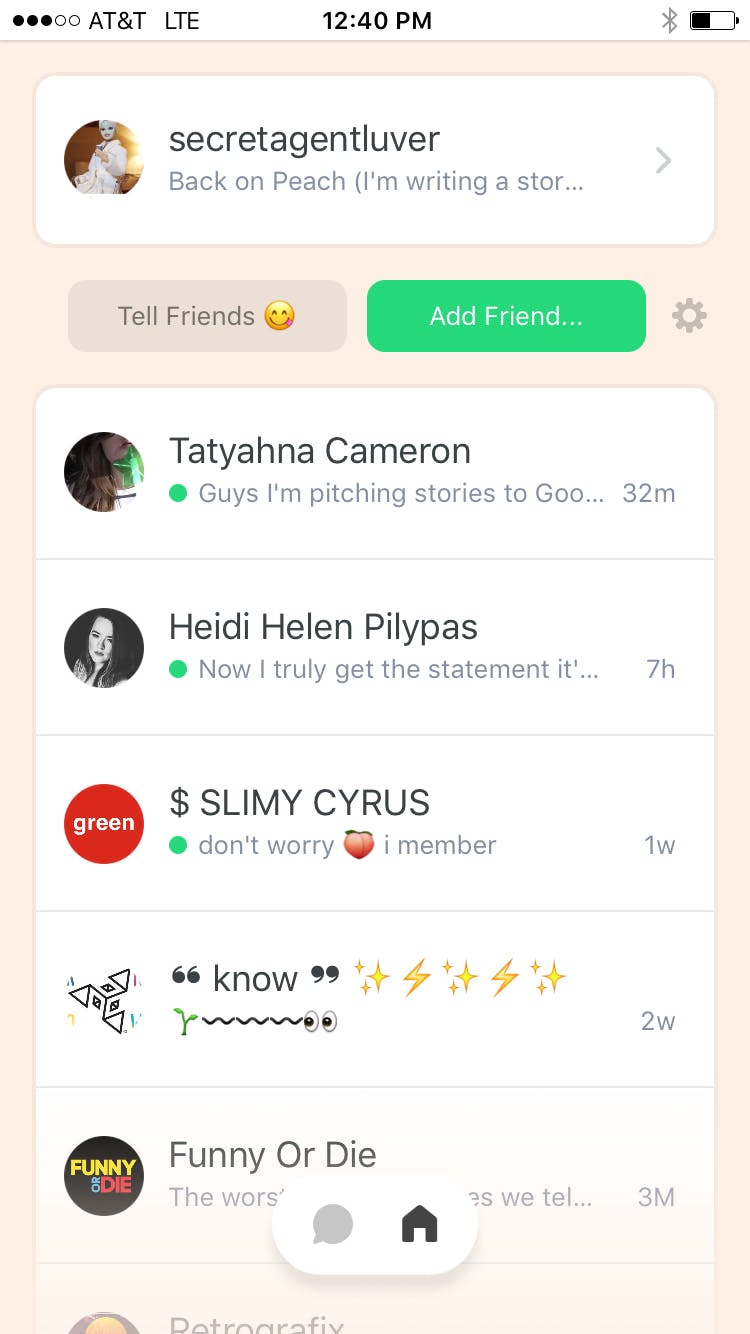

Cameron compares it to Xanga—an apt comparison because something about Peach feels a little bit Social Media 1.0. The first thing you notice when logging on Peach is that there isn’t a centralized, chronological feed. Instead, your Peach friends’ posts are obscured next to their names, and you have to click into their profile to see what they’ve posted, creating the effect of reading someone’s journal that day. Andy Pacheco-Fores, 28, compares it to “visiting each of your friends and catching up.” It’s also a fairly private platform. Upon creating an account, you’re asked if you’d like to make it personal or public; the “personal” option is auto-clicked, which almost seems like the app is encouraging users to keep their accounts private.

We’ve become savvier at crafting our online personalities, knowing how to employ just the right amounts of irony, bizarreness, personal information, and real emotion. Sadness on the internet is, if done well, stylish, funny, detached, expertly self-deprecating, and perhaps, void of certain details that might be a little too real—details that might make you look too earnest. There doesn’t seem to be any hedge-trimming on Peach, maybe because you don’t have to workshop material in 140 characters, and also maybe because everyone forgot about the app, making it a fairly safe, lowkey place to open up. You can give a lot of yourself on many corners of the internet without revealing many details at all of your IRL life. Peach is different: Its users let it all hang out.

“People, myself included, let themselves be a lot more raw than we are on other platforms,” Andy Pacheco-Fores, 28, says. “We complain, talk about feelings, and support each other in a way that would feel kinda weird and insincere on a different, more public platform. I can’t speak for anyone else but my circle of Peach friends is maybe a dozen people, if that, and no one who isn’t my friend on there can see what I post. It feels like everyone who you know on Peach knows you back, and no one on there is a stranger.”

Peach is different: Its users let it all hang out.

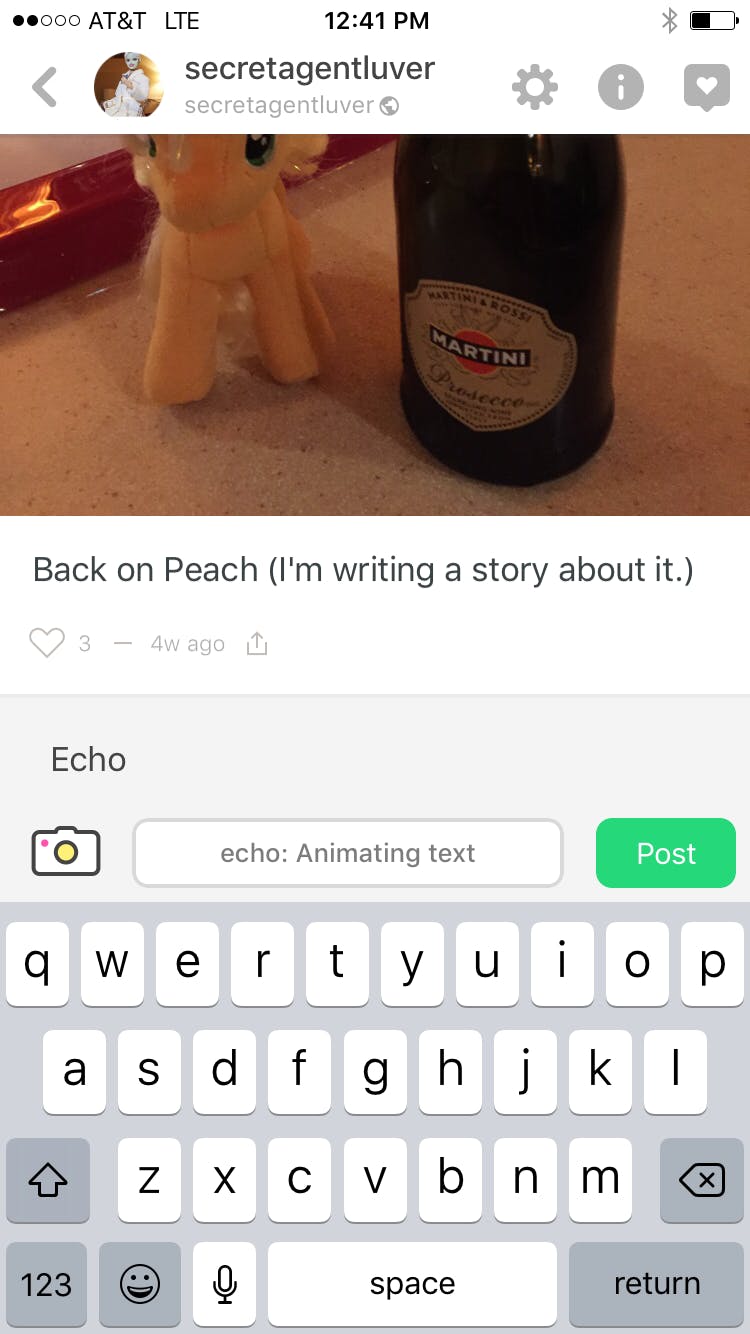

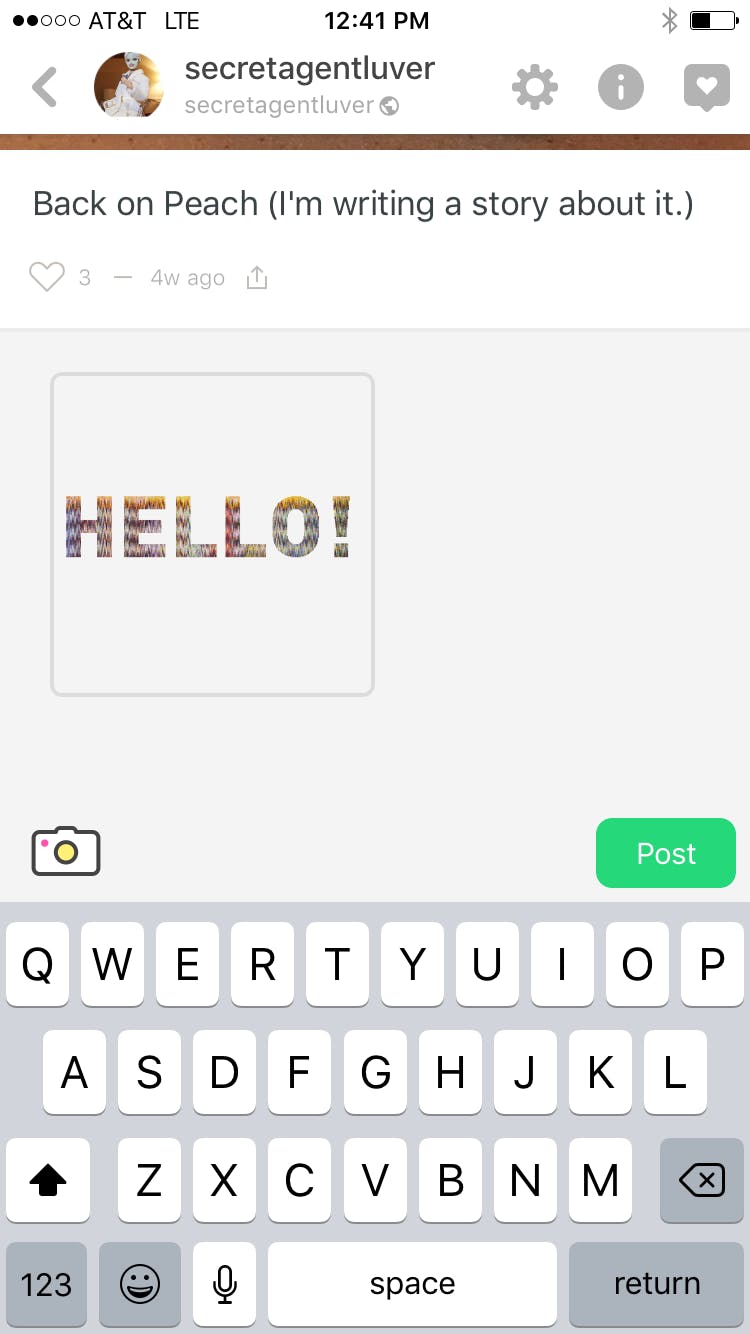

Peach’s accessories verge on being cheesy: There are post prompts that have users answer questions like “What’s your favorite thing about yourself?” and there’s a function called “magic words.” In the “write something” box where users posts, if you type certain words, other activities will be activated. Typing in “echo,” for instance, summons a pop-up to animate your text with GIFs, and typing in “song” allows your phone’s microphone to identify a song playing.

The best social platforms are like children’s toys: brightly colored, a simple interface, and enough abstract space to project ourselves onto. There’s something about Peach that feels open-ended, like there might be a next level of the game to access. Without much of an “explore” option (save for a “Who to Follow” button that turns up only a handful of public profiles), people are out there, but you can’t reach most of them. New Republic writer Navneet Alang explores this intangible aspect of Peach, something critical theorists call “affect”—the core aspects of being a person that we don’t quite have words for: emotion, intensity, and pre-conscious thought. Alang writes:

“What is initially discombobulating about Peach—the fact that there is no centralized feed, for example, or that you often discover the magic words by accident—actually focuses on what is compelling about social apps: Into their blankness, we project our desire for other humans.”

If Peach seemingly hits the checkmarks for a successful social platform, why hasn’t it caught on? “I feel like there’s a lot there,” Cameron says. “It’s so busy. There’s all the magic words and stuff, and there’s so much going on that, when you’re new to it, you don’t realize that most people don’t use that stuff—when really it’s just like longform Twitter.”

The best social platforms are like children’s toys: brightly colored, a simple interface, and enough abstract space to project ourselves onto.

Why are Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat the entrenched networks, the ones we check compulsively throughout the day? These platforms mix business with pleasure or, as Alang writes, combine affect with practicality. We use Facebook to suss out potential roommates and keep in touch with family, and Twitter connects you with people in your field just as it connects you with bizarro accounts like @Dril. But what makes those platforms so much a part of our everyday lives can also create some cognitive dissonance. It’s difficult to make your persona on Twitter all-encompassing of who you are or want to be, to successfully interweave surreal internet humor with everyday earnestness and professional networking.

Maybe it’s OK, and maybe it’s easier to have some delineation between those personas and not have them all coexist on one platform. What might be the downfall of Peach—the lack of an “explore” function, its privacy—might also be its best traits if you’re looking for a place to let your guard down.

“I guess my Twitter is more professional,” says Heidi Pilypas, a 26-year-old Australian designer who works in UI and has made apps like Stamp Pack and Gold Stars. “I recently released some apps of my own, and a lot of people who follow me are also in the industry. When they read my tweets, I mostly want it to be professional and nothing too personal that would cause a problem for me maybe. None of my family and friends are on Peach. … On Peach I find that people are very supportive and interested; they’re actually kind people.”

Pilypas does concede that, particularly as a designer, there are some things about the app she would change.

“The feed is designed in a way so that you can only see a snippet of what the person posted, and you have to click on that snippet to view the whole thing,” she says. “I don’t find that to be an easy way of browsing. I prefer Twitter’s timeline where you can see the whole thing and see things in the order they occur. I would like to see a more advanced feed. The further it is from getting updated, it’s more difficult to use. It’s got bugs and a slow loading time.”

Cameron has also noticed the bugs Pilypas mentions. She says there are times when the app will load slowly and crash, and for a while, videos wouldn’t play. The bugs, she says, seem to end up fixed at some point, “which is good because if they weren’t getting fixed … you’d know it would be the end of Peach.” While Pilypas wishes Peach emulated Twitter’s centralized feed, Erika Bocanegra, 24, likes the way it’s set up, with a little green dot by a person’s name to remind you to catch up on their posts. It’s personal, the way you might look back at texts you missed at the end of the day.

“f you don’t feel like you can catch up on everyone’s posts, the little green dot will still be there,” Bocanegra says. “You can come back to it when you have time. I think Peach can definitely become a very positive place because you can own negative thoughts, and you’re allowed to just be as depressed as you want to be.”

It would be remiss not to state the obvious that you can, technically, do be as depressed as you want to be on Twitter or Tumblr or Instagram. The difference with Peach is that, whether designers fully intended this or not, the base of its functionality, its bones, lies in being an inherently private place. If you make your profile on Twitter or Instagram private, you’re sort of going against the purpose of the app. With Peach, it’s almost like you’re supposed to make your account private. This clearly isn’t a useful function for businesses, which is likely another key reason why the app might not find its legs.

“It’s not made in a way that facilitates connecting with a ton of strangers like on other apps,” Pacheco-Fores says. “As far as I know, it’s always a two-way street so you can’t filter down to just people you want to keep in touch with without blocking/unfriending people you don’t care about. [Peach is] designed to build relationships, not audiences, and so it’s probably hard to make money through Peach.”

It’s difficult to discern whether the platform plans to stay around. Dom Hofmann, the developer of both Peach and Vine, recently posted that he would be fixing the bugs on the iOS 10 version. Emails to Peach went unreturned, and the app exists now under the umbrella of Hofmann’s other app, Byte. (Byte seems to be, in broad sweeps, a creative platform with basic software development tools that allow users to pull in content in the form of images, text, and memes.)

Peach might continue to find its niche as targets of harassment on other platforms (cough: Twitter) seek a safe haven. Maybe the secret will get out and the app will attract more and more internet kids looking to escape the limitations of their online personas. Or it may just continue to exist as a very welcoming clubhouse until one day it’s not there anymore.