From its origins in the 1970s post-punk movement to its consolidation during the following decades as a subculture of its own, goth is global. In Brazil, the gothic movement went through a major reorganization with the help of Carcasse, which hosted a web portal and forum.

Carcasse was among the first music sites to capably transpose zine culture online; to cover a regional scene with color and lived-in clout. It hosted dozens of alternative bands’ songs. From the site emerged parties, books, the only virtual shop where those who lived outside the main city centers could get works of art, and CDs of alternative Brazilian and foreign bands at a time when nobody imagined the arrival of e-commerce giant Amazon in the country. And by focusing on diversity and inclusion, looking past scenester politics about genre labels in order to connect goth fans everywhere, its legacy endures as one of the most influential sites in South America.

The beginning of Carcasse

For years, Carcasse was the main portal of gothic culture in Brazil and was fundamental in bringing together the so-called “scene”—especially in São Paulo, but it also had ramifications throughout the country.

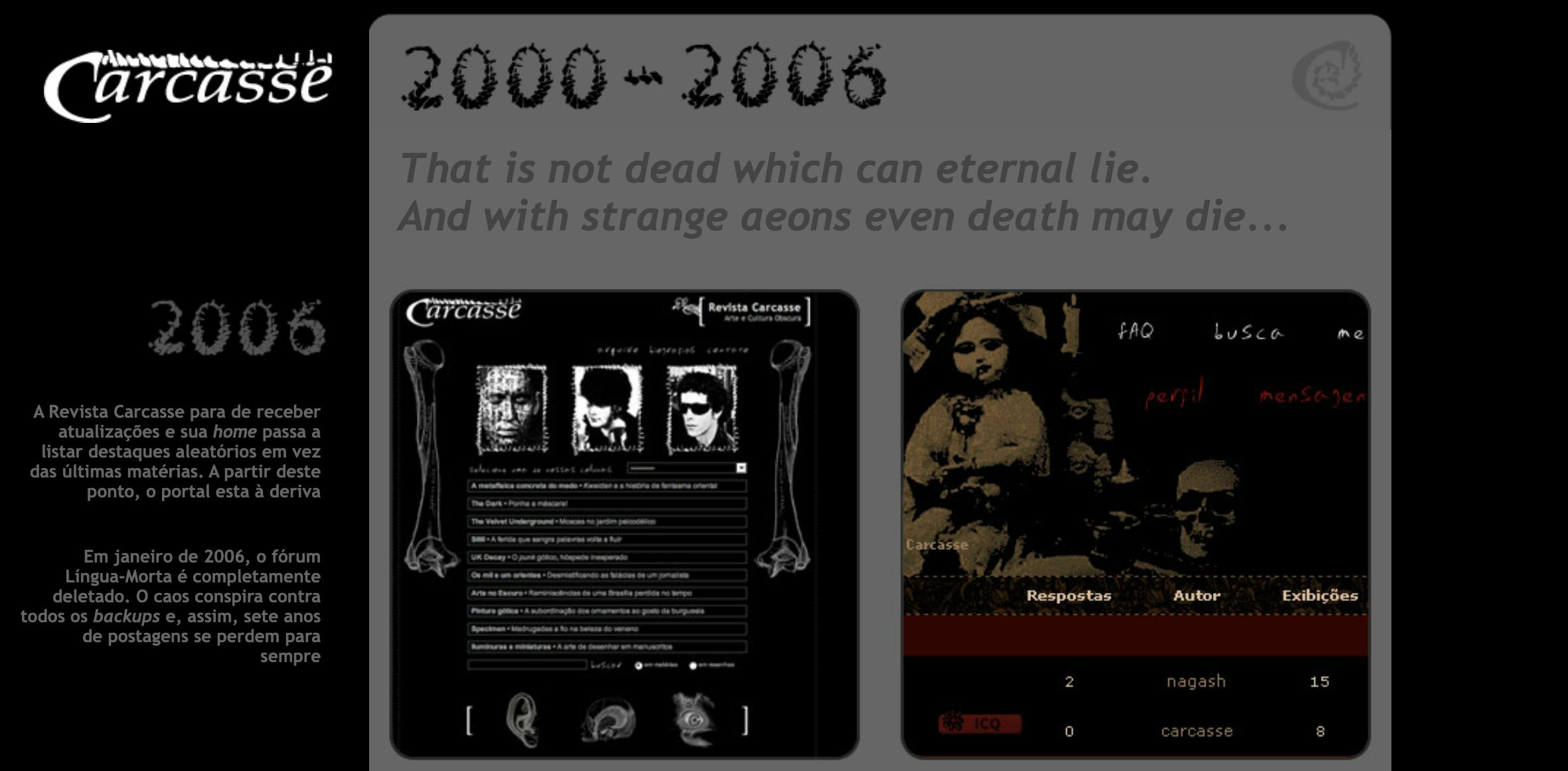

In 2000, when the internet was mostly dial-up in Brazil and it was still struggling to reach the whole country, the portal gothic.art.br was born. It then adopted the name Carcasse, and the site’s forum became the cornerstone of the whole endeavor.

“Carcasse served to define what goth culture would become, and it also connected people,” explains Nagash, a web designer and one of the founders of the project, adding that through the site, they “helped launch a box set of Coffin Joe [a Brazilian horror character] movies, launched a book, Voivode, and helped to define what goth is in Brazil and how people identified themselves as goth.”

It was the site’s magazine, Carcasse, that inspired the name of the website. (Carcasse is the French word for carcass, a dead animal body.)

“Gothic.art.br, at the beginning, was a portal that hosted about 20 or so national sites at the time. And then we started the portal’s magazine, Carcasse, but we soon realized that people were referring to the portal as Carcasse,” says Cid Vale Ferreira, a book editor and another founder of Carcasse. “So the site was renamed Carcasse with an mp3 section—something very rare at the time, a lot of national stuff which I negotiated band by band. It was a lot of work, but it worked very well.”

In the portal, lovers of obscure music could meet, from post-punk, going through metal and arriving at electronic music; to those who had a passion for literature, either reading authors such as Edgar Allan Poe or Charles Baudelaire, or writing their own short stories and poetry; and those who were interested in magic, occultism, ancient religions, and even Satanism. In short, it was a community which met for years in a single portal and in a thematic forum which, by the standards of the time, could be considered immense—there were at least 9,000 subscribed users.

“We never intended to become the biggest gothic website in South America,” says Nagash, who was even invited to redesign the then-biggest gothic portal in the world, Darksites, at a time when Google was not yet relevant and people sought portals to find the kind of content they were interested in.

‘Define goth culture’

Carcasse’s forum was opened in 2001 and attracted different generations of people interested in goth culture. The website served as a hub for artists to express themselves, hosting comic strips, producing zines, and creating a solid community.

Nagash explains that “Carcasse served to define Brazilian gothic culture. We always had this question of using this term ‘gothic’ or not—we had a subtitle, “Carcasse, virtual community of dark art,” because [the site was about] more” than gothic culture.

“Most gothic artists don’t use that term, they don’t like the term, so we always tried to leave it in more open terms and not label it,” Nagash continues. “It was tiresome. Goths spent a lot of time thinking about what it was to be or not to be goth.”

Segmented parties were common in various parts of the country. There were parties for those who liked post-punk music, for the headbangers, and for electronic music lovers. There was rarely communication between these groups. Hence the importance of Carcasse and also a gathering called the RIP party which, according to Nagash, “embraced all the strands. RIP was an attempt to bring everyone together and it was a bit difficult at the beginning. Even friends criticized the musical choices, but as time went by, people accepted the diversity.”

And it all started with two teenagers with too much free time. Ferreira, the other founder of Carcasse, started going to “a place in São Paulo, Forbidden Planet, a [role-playing game] RPG and board game shop, and I ended up meeting someone who became one of my best friends and who showed me things I really liked, like horror movies and bands.”

Through older friends and his brother, he started discovering so-called gothic literature and going to nightclubs at the age of 13.

After several years just frequenting the scene, without any involvement with production or creation, Ferreira says he started to “fall in love with fanzines” and made a gothic fanzine, Sépia Zine, that he launched at the beginning of 1998. “I had, with the zine, my baptism as someone who was producing something for the scene,” he says.

The zine was fundamental to what would become Carcasse years later. Ferreira kept a mailing list for Sépia Zine with hundreds of people, many of them musicians, artists, and people who contributed to the alternative Brazilian scene. It was around this time that, at the age of 17, Nagash met and became friends with Ferreira.

“There were a lot of people who wanted to do a website, like the [rock band] Sisters of Mercy fan club, and I did the website,” recalls Nagash. “I ended up doing websites for everyone.”

In 1999, the idea came up to look for a way to finance a more ambitious project and the two then developed a project for the Itaú Cultural Foundation, a cultural institution in Brazil. Although well-received, the idea was not selected for funding, but they decided to go ahead with it anyway and counted on the help of many people in the scene.

Nagash explains that “when we opened the forum the project grew a lot, a lot of people wanted to participate, including people who had a career in film afterwards.” (That included director Victor Hugo Borges.)

“Then just me and [Ferreira] couldn’t handle moderating the forum, so we had volunteers,” Nagash continues. “We had to create an email address to receive commercial proposals, every band that came to Brazil wanted Carcasse to advertise, sponsor—but we didn’t even have the structure for that. People thought we were a mega-company, but we were just two kids at home.”

The end of Carcasse

The two boys at home have grown up.

“When I was 25, I started working in a big publishing house,” says Ferreira, “and the work we did on the site consumed me 4 to 5 hours a day. When you’re starting out in adulthood you need to sacrifice some things, and I also noticed a change on the internet itself.”

They were no longer teenagers. Nagash was given an ultimatum by his boss at the time: either Carcasse or his job. He chose to keep his job.

At the height of its popularity, the site was frozen. The forum was lost after the hosting company took it down in 2006 for a reason as trivial as not updating the PHP version they were using—at the time, they didn’t have anyone capable of doing the laborious update on the scripting language.

“We did everything for love and idealism, but people were also growing with us and changing their priorities in life,” explains Ferreira.

All those involved in the portal were volunteers. Nothing was monetized—Ferreira would not allow it.

“Even when we created the shop, it was something I had to fight with him about,” says Nagash. “We were selling T-shirts, the T-shirt cost R$ 10 (equivalent to $1.82 USD), but [Ferreira] wanted to sell it for R$ 7 and people wanted to buy it, but he didn’t want to make money out of Carcasse.”

The shop was a short-lived and extremely amateurish initiative. There were no automatic shop systems behind it yet, so the shop served to showcase products—books, CDs, T-shirts, artwork by portal collaborators—and the sale was done on a one-on-one basis. But the idea was in itself innovative because, at the time, it was difficult even to get items from other parts of Brazil, let alone outside the country.

“I could never have imagined that the site would reach the size it did. It was something that exceeded the best expectations. It was a time when we did things without any idea of how many people would answer the call—you’d publish something and suddenly…” says Cid, leaving the size of the portal’s success in the air.

Today, a static version of the website is still available, managed by Ferreira. It includes several old event flyers and is headed by an H. P. Lovecraft quote: “That is not dead which can eternal lie, / And with strange aeons even death may die.”

Carcasse was a milestone in the Brazilian goth scene, helping to consolidate the movement and unite different people under one roof. And the site had a monumental influence on its users.

“Before it, I knew very little about goth culture,” says Daniel Caliban, one of the most active users of the portal.

An Illustrator and designer, his art brings together much of what he learned in the years he was active at Carcasse. “It’s no exaggeration to say that the forum helped form my character. I spent a lot of time on the forum, I learned a lot, I had fun, and I got informed,” he says, adding that “being from Rio de Janeiro, the feeling I had was that the influence was huge because almost everything I knew came from there. Today, with more distance, I can better separate my experience and its real size.”

“But for me,” he says, “there’s no way of talking about gothic subculture in Brazil and not mentioning Carcasse.”