Two computer scientists believe they can see into the future.

Building on cutting edge machine-learning and data-mining techniques, a pair of Carnegie Mellon University researchers have built a new tool designed to accurately predict which Web servers will be hacked before any hacking actually takes place.

Call it pre-cybercrime.

Kyle Soska and Nicolas Christin, the academics behind the new classification algorithm (they call it a “classifier”), say they trained their tool on 444,519 websites archived using the WayBack Machine, which contains over 4.9 million Web pages.

The classifier correctly predicted 66 percent of future hacks in a one-year period with a false positive rate of 17 percent.

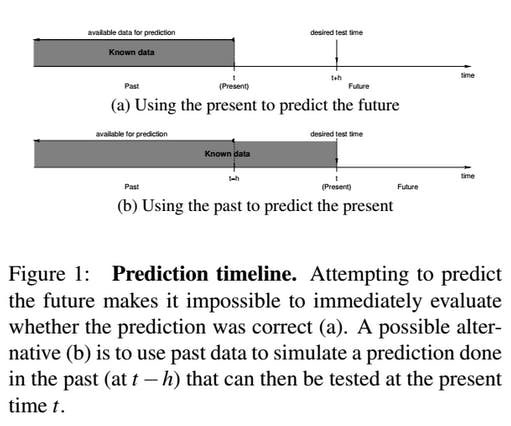

That performance is “very encouraging,” the researchers wrote in a paper published Wednesday at the USENIX Security Symposium, “because we are essentially trying to predict the future.”

The classifier is focused on Web server malware or, put more simply, the hacking and hijacking of a website that is then used to attack all its visitors.

If it is possible to accurately predict which sites and servers are most at-risk, it becomes easier to keep an eye on and warn against dangerous websites, the researchers say. Website operators can be alerted ahead of an attack, and search engines can easily know which websites to keep an eye on for potential exclusion from search results.

The algorithm is designed to automatically detect whether a Web server is likely to become malicious in the future by analyzing a wide array of the site’s characteristics: For example, what software does the server run? What keywords are present? How are the Web pages structured? If your website has a whole lot in common with another website that ended up hacked, the classifier will predict a gloomy future.

The classifier itself always updates and evolves, the researchers wrote. It can “quickly adapt to emerging threats.”

Although the classifier has already looked at almost 5 million web pages, it’s eventually going to target the entire Internet, even as it expands and changes drastically over time.

By starting with a set of confirmed hacked and malicious websites obtained from blacklists like Phish Tank, Soska and Christin were able to use the Wayback Machine’s archived copies of websites across time to track their transition from secure to compromised.

Here’s the foundational bit of magic: Learning from what it sees on the Web now and what it can see from across the Internet’s history on the Wayback Machine, the classifier dynamically extracts a signature feature list from hacked and malicious websites. The common denominators from discovered malicious servers are then used to help predict the future for other websites.

“For instance, if a certain website suddenly sees a change in popularity, it could mean that it became used as part of a [malicious] redirection campaign,” the researchers wrote. The presence of a “wp-admin” directory indicates the use of WordPress that might be exploitable if it’s running an older version. Looking at load time, links to the site, the state of comment sections, and even CSS tags can be meaningful indicators about a website’s future.

The content you personally put on your own website—the particulars of your latest blog post, for instance—is virtually useless to the classifier. But certain HTML tags and keywords can give big clues about a website’s vulnerability that the classifier learns about. It can then can alert not only the researchers but the website’s owners as well.

As Soska and Christin explain (for those of you with a bit of HTML know-how):

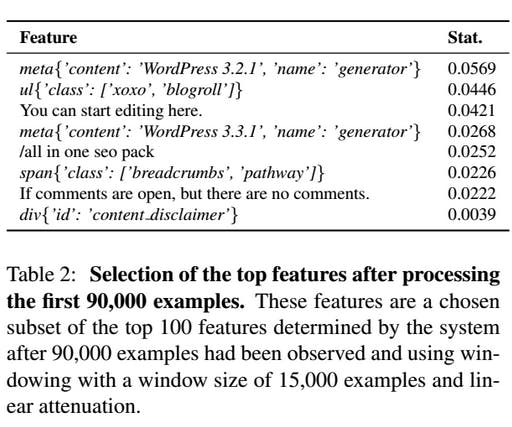

“The feature ul{’class’: [’xoxo’, ’blogroll’]} was observed in 736 malicious sites and 1,027 benign ones (461.34 malicious, 538.32 benign after attenuation) making it relatively more frequent in malicious sites. The feature div{’id’: ’content disclaimer’} was observed in no malicious sites and 62 benign ones (47.88 benign aftter attenuation) making it more frequent in benign sites.”

If your website is similar to others that were hacked and hijacked, the classifier will try to find out and let you know before the damage is done. The software will eventually be released to the public.

The classifier isn’t perfect, however. While it looks at things like traffic and content, it doesn’t consider bad passwords, social engineering, or any number of alternative attack vectors that bring down websites across the Internet on a daily basis.

But within its limitations, Soska and Christin’s new fortuneteller seems to do a hell of a job telling websites that their time might soon be up.

Photo via Holget Niemann/Flickr (CC BY ND 2.0)